A Biblioasis Interview with Maya Ombasic, author of MOSTARGHIA

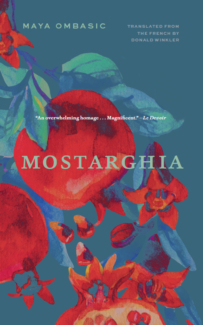

Maya Ombasic’s gorgeous, lyrical memoir Mostarghia arrived in Canadian bookstores this week! (Don’t worry, U.S.—it will appear there in a week and a half.)

Maya sat down and answered some of our questions about the book Le Devoir called “An overwhelming homage, clear-eyed and drenched in tenderness, Mostarghia is driven by Maya Ombasić’s strong, sensitive voice, which allows us to glimpse the reverse side of the shadow of exile. Magnificent.”

For those who are coming to your work for the first time, can you tell us a little about yourself and your writing?

I was born in a country that no longer exists, in a place where living alongside people of different cultural identities was as natural as breathing. Everything that’s come since (for almost three decades now) has been an attempt to understand why the country no longer exists and how I can make sense of the whole experience, first as a daughter and a sister, and then as a mother, a woman, and an artist. How to survive after a physical and metaphysical disaster? Because once you’ve been awakened from your cozy and happy childhood, had your roots torn away, and been forced onto a boat that will take you forever away from the reassuring valley you’ve called home, the universe is no longer a warm and benign place. Today there are several geographic locations in the world where I feel “good,” but no place offers the unique metaphysical reassurance of “home.” The war that ended my childhood also destroyed that for me.

I do not like the words integration, assimilation, success story, because I do not believe there’s any such thing as successful exile. Why? Because the whole process inevitably leaves behind what the human being holds most sacred: the feeling of belonging to a place, a language, a culture, a territory from which the meaning of life emerges. To have those sacred bonds brutally torn away is to face, at the age of twelve, brutal nonsense. I learned very quickly that it was now up to me to give my life meaning, while also keeping in mind that not everyone can, or wants to, “custom-make” their own life’s meaning. This is the experience I try to relate in this book through the emblematic figure of my father, who is not a “successful” immigrant. Of course—and inevitably—questions of memory, transmission, identity, and exile (or what they really mean, on a metaphysical level) have become my obsessive quest.

Your book takes its title from a portmanteau of Mostar, the city where your father and you both were born, and Nostalghia, the title of an Andrei Tarkovsky film. What about this film made it so important to the way you tell your father’s story?

My father died at the age of 54. During his short life, but especially during the early years of our exile, I lived and grew up in the shadow of a tragically Slavic man. He could have a fit over anything. He could fall without warning into long moments of melancholy in which he recited by heart his favourite poet, the Russian Sergei Essessine; at the same time, he could be extremely funny, because he was a master of self mockery. I have often tried to understand him, without success—he was unpredictable and elusive.

Then one day, by chance, I came across the film Nostalghia. It was being screened in a small Parisian cinema that was doing a retrospective of Andrei Tarkovsky’s whole filmography. As I watched that movie, I had the impression of meeting my father, not only in the main character, the poet Gorkachov, but also in the filmmaker’s eye: his choice of shots, his landscapes and his colours, which all speak unanimously the language of nostalgia. The protagonist, in exile in Italy and on a quest to learn about a sixteenth-century Russian artist who lived in Italy, cannot overcome his melancholy and homesickness. He wants to return to Russia, but it seems impossible. Later, I read Tarkovsky’s biography. He, too, lived in forced exile, far from his family and friends; nostalgia emerged as the main theme of his artistic quest.

When I discovered Tarkovsky’s work, I understood my father better (not to mention that physically they looked as alike as two drops of water).

Early in the book, you equate learning a language with accepting a social contract. Can you elaborate on this idea?

From the moment we put aside our mother tongue in order to learn the languages that will help us integrate into our new society, we sign a new social contract. Not to learn its language is necessarily to be outside of a society. My father never wanted to go through this process; whether that was a positive choice or simply out of spite, I do not know. What is certain is that he willingly remained outside of Canadian society and the Canadian social contract, sometimes for better and sometimes for worse.

Let’s start with the worst: I was his assigned translator, his indispensable crutch; he had no contact with the outside world that did not pass through me. As for the best: he had direct access to reality beyond language and the social contract. He had an amazing ability to understand situations, people, and the world beyond language. In other words, he had a direct experience of life. As he was a visual man, he pictured reality, especially in metaphorical images. This is an advantage in itself, because it allowed him to access emotion directly, without going through the intellect or the cogs and gears of language. But his linguistic handicap was above all a burden for me.

Talk a little bit about the part Cuba plays in your book.

Coming from a socialist country on the old continent, I belong to a whole generation for whom Cuba represented an admirable satellite led by idealistic warriors demanding a more just world. And when you’re young, you need ideals. As a teenager, I was desperately in love with Che Guevara because he represented my masculine ideal: a handsome, long-haired, dark and gloomy figure, but also a poet, a doctor, and a revolutionary. Then there’s my father’s love for Cuba, this utopian island where the promise of communism had not yet failed as it had elsewhere on the planet.

In the book there is a whole chapter on Cuba where I try to explain the disenchantment that comes when those ideals meet reality. In that chapter, when my father realizes that all in Cuba is not really as he imagined it, it’s like a nail in the wound his exile has already created. He has to come to terms with the realization that his lost paradise will never be found. From that moment, he sinks into a melancholy that will continue until the end of his life.

I have to add that, consciously or unconsciously, I married a gloomy long-haired Cuban who looks like Che Guevara, so my daughter is also half Cuba. Fantasy imitates reality and vice versa . . .

How do your experiences as a philosophy teacher and as a documentary filmmaker affect your approach to writing?

I’m often asked how I manage to do all of this at once, but for me, all these practices come from the same starting point. In other words, it is the same vibration, the same source, the same inspiration that unfolds in different forms. As much as the teaching of philosophy nourishes me on a daily basis, not only because I am obliged to update my knowledge, but also to share it with my students who in turn bring me a lot, the documentaries or the images on the screen offer another visual language that influences my writing. I believe in the power of images, whether visual, cinematographic, literary, or philosophical. For example, the image of the Sun of Knowledge in Plato remains vivid for me. When we come to knowledge—true knowledge—we come out of the darkness to feel enlightened . . .

What are you reading right now?

I just finished Amin Maalouf’s Naufrage des civilisations (Shipwreck of Civilizations). He is an author that I admire a lot, and his latest book puts into words what I have been feeling for some time: that we’re living through the decline of civilization and the return of barbarism. Depressing book, but necessary for all those who are trying to understand our time.