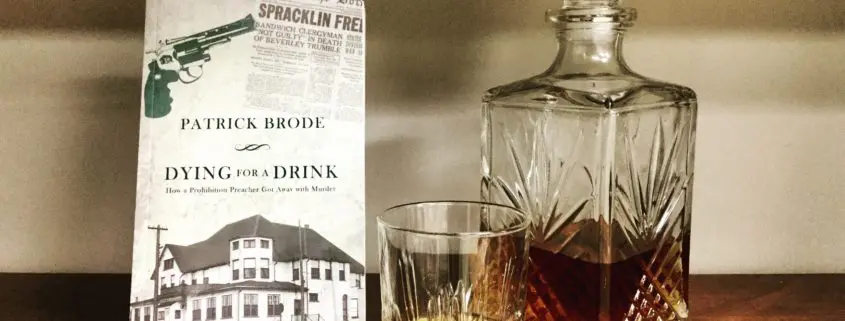

A Biblioasis Interview with Patrick Brode, author of Dying for a Drink: How a Prohibition Preacher Got Away with Murder

We’re delighted by this week’s arrival of beloved local author Patrick Brode’s Dying for a Drink: How a Prohibition Preacher Got Away with Murder. Brode’s latest tells a story that’s familiar to many Windsorites and guaranteed to captivate anyone who’s interested in the history of the Prohibition era. We sat down with Pat to find out more about the true story behind this local lore.

For those who might not be familiar with your work, can you tell us a little bit about yourself as a writer and a historian?

I have been writing legal history since the 1970s. My publications so far consist of biographies and studies of unique issues such as sexual “seduction” and its consequences in Canada. Many of my writings have been case studies, which have focused on specific cases. For example, I have written on the 1860 extradition trial of the escaped slave John Anderson, the 1895 murder trial of a black woman, Clara Ford in Toronto, and the prosecution of a serial killer of homosexuals in Windsor Ontario in 1947.

Babe Trumble’s murder is a well-known story in the Windsor region. What drew you to write about this particular case for a national—and international—audience?

What makes the murder of the saloonkeeper Babe Trumble by a Methodist clergyman so compelling was the way in which it so captured the opposing forces of the Prohibition era. That a religious figure would shoot down and kill a man who had the nerve to sell alcohol became the high water mark of religious zealotry in Canada. It became a turning point in which the public began to question the validity of morality by government force.

I was struck by the extent of Toronto media coverage of this case, and the ways in which Toronto was so at odds with the Border Cities region over the alcohol issue. Can you talk a little bit about that dynamic?

All major Toronto newspapers sent reporters to Windsor to cover the early rum running events. Their coverage was inevitably sensational with accounts of running gun battles, and bloody confrontations between police and bootleggers along the shore of the Detroit River. It made for exciting copy, and the Toronto public loved it. Part of it was vicarious thrills. The Windsor area was often referred to as the “Essex Frontier” as if it was the Wild West. It was portrayed as a dangerous place where everyone carried a gun and was ready to use it. The Toronto reading public was entertained by but safely removed from this mini-war going on 300 kilometers away.

The Windsor region has always been intertwined with that of our American neighbours across the river in Detroit. How was the Detroit region affected by the hullabaloo recounted in Dying For a Drink?

Throughout this incident, the role of Detroit as the great magnet for Canadian booze is central. Both cities had nothing but disdain for the prevailing liquor laws and intended to defy those laws for their mutual benefit. The almost overnight growth of the cross-border smuggling trade was a business phenomenon that made millionaires out of cab drivers. But to prohibition true believers, such as the Reverend Spracklin, this was a defiance of morality which had the force of law. It had to be stopped.

Today, Windsor seems fondly proud of its rum-running past, almost part of our civic heritage. Has it always been that way?

There was almost a romantic “Robin Hood” feel to the period. Ordinary people were rising up to resist a law that had little popular support. It is one of the few instances where so many people in a Canadian city openly broke the law. For that reason, the “Rumrunner era” continues to resonate. The descendants of bootleggers proudly display relicts of their family’s past and tours celebrate the persons and sites of the era.

The Prohibition era has an extensive mythology—you’re very careful to ground your work in facts and not legends. Are there any persistent myths you come across while working in that era’s history?

That one of the many who broke the law was shot down and killed for his defiance shocked Windsor. It was a further measure of the times that in most of the rest of the Ontario the respectable classes thought he got what he deserved.

In many ways the incident has been embellished since 1920. It has been romanticized to suggest that the killing was the result of an ongoing feud. It has also been suggested that the Reverend Spracklin was a Canadian “Eliot Ness.” Neither view has any substance and detracts from the real facts that brought them together in a tragic, spontaneous clash.

What are you working on next?

I’m working on a further legal history on the war crimes committed against Canadian servicemen at the end of World War II and the resulting courts martial.