Tell me a bit about yourself.

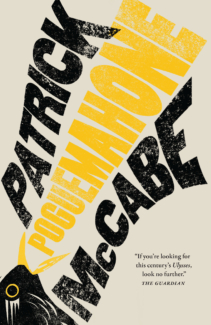

Well, I suppose I have been a full-time writer for twenty years now. I used to do other jobs, but they are not of any interest to either me or your public. I suppose I have written a lot about contemporary Ireland, the ancient world, and the interplay between them.

How does the ancient world—folklore, myth—influence your work?

I was brought up on the Catholic Gaelic tradition, you know, which is filled with all sorts of contemplations of alternate worlds and alternative realities and that is always really appealing to a child. In my case, it became comingled with what we call the “culture of the degraded image.” Popular culture like horror movies, comic fiction, TV, all sorts of things. The various manifestations and expressions of the inexplicable in the modern world and the ancient world became one for me. That is very true of Poguemahone. It is ancient folklore and contemporary folklore performing a progressive music dance.

There is also an element of hilarity and self-parody as well. I suppose what I like to do in fiction is to do battle with the English language. There is a sympathetic understanding between the two languages—that is to say Gaelic and the English language—in the book but also a kind of mischievous duet. It has been said that the characters speak in English but feel in Irish. Feel in Gaelic, in the Catholic Gaelic tradition, but speak in the Anglo-Saxon, more pragmatic, straight-talking tradition. There is a lot of that kind of dancing going on. Language dancing around itself, as it were.

It is evident on the page and, well, in moments where characters don’t realize they have slipped into Gaelic. Those moments are very poignant.

Well, it is a serious book and, poignant is what I was looking for. It is ultimately about the greatest horror I’ve ever experienced, which is Alzheimer’s. I haven’t experienced this personally, but I have been very close to it. If in the ancient world people said a spell had been cast either on a person, or a town, it might seem to the rational or contemporary mind to be a ludicrous superstition. But, when you are close to Alzheimer’s, it is as good an explanation as any. Because that is what it looks like.

In the age of TikTok and in the age of the information superhighway, we know everything and we know nothing more than the ancients really. A simple plague can knock everything out. If this had been a bubonic plague, none of these things would have counted for anything. They would have just been toys. It might happen yet.

Yes, it might happen yet. I mean, it is obviously a raucous book. But I found it to be quite serious throughout.

It’s meant to be deadly serious—it is the most serious book I’ve ever written. The overlay of hilarity, self-mockery, and parody is just that: an overlay. The subterranean river running through it is one of dread.

My next question is about your narrator—

I’ve been married for a long time, 40 or 50 years now. I’ve got 2.5 grandchildren, there is one coming in May. I’m sort of a traditional anarchist, as it were. Imaginatively anarchistic, socially traditional. I like order. It is very easy to be anarchic in your imagination if you are ordered in your life. If you are disordered in your life, all hell breaks loose on both fronts. I like steadiness.

When I was reading, I couldn’t help but think of Joyce, Nabokov, especially when thinking about Dan, and the role he plays as the narrator—

As a young man I was very influenced by both of those writers. I suppose who you encounter first leaves a lasting mark. I read all of Nabokov’s work, some of it I liked more than others. I mean I found Ada impenetrable. But the other ones are linguistically very exciting. It is all about language in a way for me in the end. If you get the beat and the rhythm and timbre of a language right, the novel usually emerges through the language, through the cracks between the words. I don’t start off with a story, I never have an idea of where it is going to go. I just follow the language.

This book started off as a traditional, chapter-based book. When I saw what I had, I was in despair, and felt like tearing the whole thing up. I didn’t like it, didn’t think it was original enough, and then a couple of things happened that kind of released the book. It was like an emotional pressure valve that, when released, the book came out. And it came out in an entirely different form than originally anticipated.

And that was very true with this, you know. A lot of it is set in the 70s and to the kind of rhythm of the 70s, like Dylan’s Desolation Row or the poetry of Gregory Corso and William Burroughs. It is at once an homage and a means of acknowledging the rhythms of an age which, for me, release the emotions of an age.

A prospective publisher said to me: “I don’t understand why it is written in this middle of the page kind of poetic style.” I said, “well you know, if it is good enough for Ginsberg, it is good enough for me. If it is good enough for TS Eliot, it is good enough for me. But also, didn’t you know that Irish Leprechauns speak in iambic pentameter?” And he said, “no I didn’t,” and I said, “well they do, and I’ve seen them.” At that point, he terminated the phone call.

Yes, well, I am a reader of poetry first and I think, you know, opening a 600-page book of poetry can be daunting for anyone, at first. But it immediately became viscerally clear why you chose this form.

Yes, well, I completely understand those concerns. If it is difficult to read a 600-page book of poetry, it is equally daunting to write it. I didn’t want to write it unless the story barreled along and was very clear. I am no fan of opaque epics. I love poetry but if something is keeping the reader out, rather than bringing the reader in, particularly now more than in any other age, it is already lost. Because of the proliferation of visceral imagery now, you notice at the theatre or movies, the audience will give [something] ten minutes before glazing over, unless there is something going on that is of interest to them.

So we are in a different time, concentration-wise. I was well-aware of what the challenges would be. But I think once I got the note struck, whoever is going to be interested in this, they are not going to be willfully excluded from anything I have to say.

Yeah, well it is quite stunning, and, in that way, very clear.

That is very important. Nothing maddens me more than a poem that eludes you unnecessarily when you could have been brought into everyone’s advantage, especially the author’s.

When you were thinking about Dan, as the speaker, was it important that he was unstable, unreliable?

If you think about what is happening, it is like a basilisk or a virus (to which we are all accustomed now) has gotten loose. It is the basilisk of vascular dementia, and you don’t know what way that is going to go. You don’t know if what you are being told is the truth, or if it is one time the truth, and next time not the truth. That is the way that affliction works.

It is also an allusion to general apprehensions of reality. The way, say, a Gaelic Catholic sees the world is not the way, say, an Indian Hindu sees the world. Is a tree the same thing to everyone? What is a tree anyway? Who calls it a tree?

These things only become apparent as you get older and you see them collapse. Like the foundation pillars that maybe held a person’s life both intellectually and theologically together crumbling in front of them. What was once very familiar is now terrifying, strange, maybe amusing, but it’s not the thing that was there before. So what is it? So then it’s very important that the narrator had a multistranded view. And the person that he’s representing—or is he representing?—what is her reality now?

It is as big a book as it is because the number of questions it is taking on is quite a lot for me. Normally, the focus is narrower than that. This one, you’ve got two narrators in one, in a way. You’ve got the Spanish/Portuguese element which represents the dreamlike world of the Latin which is very close, I find, to the Catholic Gaelic, one in that rationality moves in and out of itself all of the time. It is colourful. Linguistically it is impish, daring, and challenging in a way that perhaps the Anglo-Saxon Canadian/American anglophile world, shall we say, is not. Not that either is better or worse, they are just different.

You find those differences between Ireland and England. Superficially, they seem the same, until you start listening, and digging a bit, and you see curious gaps. Interesting gaps.

Those are minor explorations though. I suppose really what this story is, is one of exile and heartbreak. You’ve been exiled from yourself, that is the ultimate exile, isn’t it?

That was my next question: exile and the role it plays in your work. I know Fogarty—the last name of your main characters—translates to “exiled” in Gaelic. I’ve read quite a bit of exile literature, rarely from Ireland. A lot of German literature. I know there are many different ways to approach the subject. Exile from the self, the country, what kind of country you are talking about, what the historical conditions of exile are…

I love that tradition of European literature. There is an element there of stark, bony exile feel. But then there is the florid Latin/Gaelic, that is equally trying to lasso the notion of exile but is expressing it in an entirely different way. But you are still left with the empty room of Kafka in the soul. Had there been anybody there at all? Did you imagine the whole story? Where did the story come from? Fogarty also means outlaw, being on the fringe, on the perimeter of society. But what is society? Is it made up of individuals? Which brings us to Camus. I’ve been interested in L’Étranger—a couple different translations of it.

One translation would open: “Mother died yesterday.” Okay, that is one. Another translation would be: “My mother died yesterday.” Straight away you have two different books, haven’t you? They are both dealing with exile. So, “Mother died yesterday” is the more European, Anglo-Saxon statement of fact. Three words. But then, when you add “my,” it personalizes it, which is the way the Irish mind would approach it. It brings it to the village.

But it doesn’t matter which way you express it, really. The exile is still the same. You are left alone. So, definitely, there is an element of The Waste Land. Who knows anyone? Who knows oneself?

These are such heavy questions. I couldn’t have written them except for in the style in which they emerged, a rainbow river that tumbles and torrents along. It had to come out for me that way, all these other things were buried deep. The form helped them to be released.

Do you think the condition of their being in exile helped you work out other themes that exile compounds? Like madness, alienation, isolation?

If you look at any of my humble offerings. There is always an element of someone being at the center of things, but they’re not. And they know they’re not. In The Butcher Boy, there is the illusion of being happy-go-lucky, but in fact the soul is desolate. You will often find, particularly if you examine Irish history, expressions that there is some terrible loss. Maybe even just in the biblical sense, as simple as banishment from the Garden of Eden. A sense of what is missing. People search for it in good work, love, God. It often eludes them.

It seems to me, having come through a God-centered world and now, in its absence, that the exile may be far deeper than we have begun to realize.

The world as it reconfigures itself and moves at such a speed, there are sometimes in the secular world when people seem to me to speak with enormous authority without any great information. Unbelievable confidence, but when you start to pick at this technological delivery, it doesn’t do a great deal. That’s not to say that I am particularly religious, but I grew up in a world where the psalms were known to very ordinary people, they could quote things, even if they weren’t particularly well-schooled or educated, they had a relationship—however oblique—with the classical world which is now laughable…

Obliterated.

Completely obliterated, annihilated, and in fact scorned. You see politicians who are attempting to impress but are so fool-hearty and ham-fisted in their delivery that it is nothing but an embarrassment. We may come out of this, I don’t know. But I think there is some time left for it to run, before something happens, and the game is up. It certainly does embarrass me. Do you know what I mean by that?

Yes. The denigration of language that was once universal for a community. Exile as a universal, philosophical, or existential condition, yeah…

Ultimately, it doesn’t make any difference if you were here or not.

Yeah, and now you might not have the language to express or even approach expressing those feelings.

Well, that is really worth exploring. Why, it is really good to have a dialogue with younger people because when you get to your mid-20s, these things might start to be of some interest. Because the thin ice that they’re fed, it only lasts through the teens. When real emotions start to come in, the language that has been attacked and obliterated could be of service to them. You can see the difference between people who have now realized that and people that haven’t.

The ones who haven’t would be really fine writers, maybe, and competent. It’s not their fault that they have been tumbled into an age where these things have been derided, particularly in America now. It wouldn’t be the first time. It just seems to have happened at a furious speed to me. But the 50s and the 70s didn’t differ in that respect, so much.

Kind of a shift but, not really. I would love to hear you talk about the role music plays in the text.

The beat of the book is set by the appearance of one particular song, which is an old Irish, Scottish folk song called “The Killiburn Brae.” A brae is a slope or a hill. It is generally sung to the beat of a hand drum. Like a lot of work songs, it is about the war between men and women. A man speaks about sending his wife down to hell. She is so infuriating that the Devil brings her back and dumps her at the doorway of her husband’s house, saying “you can look after her, because I can’t handle her.” The lyrics of this song are not that significant, but what is significant is the rhythm. It is the first song you encounter and is the musical foundation of the book.

As it moves into different areas, you could encounter the cool crooners of the 1950s, it could be Nat King Cole, or scat beats of the 60s. When it goes into the 70s, it moves into the psychedelic, transcendental phase. You have that absorbing period between 1970 and 1974 when all sorts of outlandish experimentations were taking place. In a way, the book is an homage to that as well, insofar as it is a drug-fueled opera. This sort of thing that was very common at that time. It was possible for record companies to form some of the most outlandish projects imaginable before they ran out of road, and punk came in.

But the circular librettos of the 70s certainly inform the book, as does William Burroughs and George Corso and all those … well I don’t like the word experimental, they are all part of the canon now. They might have been seen as experimental against Tennyson but not now. Just look at Bob Dylan, the most experimental of them all has won a Nobel Prize and is regarded along with Shakespeare. Quite rightfully so, I think.

Dylan told someone that in 1972 that he was a sea-faring mariner off the coast of Barbados. It was all a pack of lies, wasn’t it Bob, and it would have turned out to have actually happened to someone like Dave van Ronk. Dylan would’ve stolen the story and convinced himself that he was there. And if he convinced himself, well, maybe he was there.

It is operating on that level. I have always been interested in that multi-layered aspect of Dylan’s imagination. He rang his mother up one time, and he said to her, “I hope you don’t mind me making up all these stories.” She had read somewhere another pack of lies about when he ran away with the carnival. She said “Oh, absolutely no dear, but why are you doing it?” and he said “oh, well, I think it helps my career” and chuckles. And, you know, I like to chuckle.

It helps with the condition of exile. There isn’t that much of Dylan in the book, just a little bit. Because he is too powerful. If you admitted him in, he could take over, then it’s no book of your own, he would scoop the prize again, like he did to Dave van Ronk.

I found it very operatic, in the way that The Wall and Quadrophenia, are.

Those albums, at their best, well, I love their absolute audacity. They really shouldn’t have the nerve to do those things. I thought that with the original 1500-page manuscript of this book, it was quite tame. Little strokes trying to burst, little veins. Then, when I got them all together, it came out in a torrent. But it was a controlled torrent. The original manuscript was solid and not as imaginative. But it provided the foundation. Like what I was saying: you live a relatively straight life so you can let your imagination go where it wants. If you are living a too dangerous life, and your imagination is going where it wants, you may well end up in trouble. And there is plenty of evidence, with the history of writers, to suggest that. It just doesn’t really work. It can be really dangerous. Anyway.

Well, you have addressed this already, in so many ways, but one of my questions is about the departure from prose. Especially as it pertains to dementia and expressing fractured consciousness. Maybe there is more you want to say on that.

I have approached it before, in other books, but I’ve never quite gone full throttle ‘til the end. It has been part of chapters here or there. I suppose, I’ve never been this close to fractured consciousness. At various times in my life, I’ve been semi-fractured myself in my perception or I have been associated with people, specifically in those countercultural days, who willfully courted distorted perception. Jim Morrison would be a great hero of ours. All these people who made it very attractive, especially to the young.

But when you are older, my age, and you are close to fractured consciousness to the extent that it terrifies you and terrifies you. You can only do it justice by writing a book like this, which addresses it head on. It is not funny. It is not a cultural fad. It is a nightmare.

Well, those are all my larger, thematic questions. My final question is what you are reading now?

I’m reading a book called Dead Fashion Girl by Fred Vermorel. It is set in the demi-monde of London’s Soho, late 1950s. I don’t know why I am reading it. There is a nexus of writing of people like Eoin McNamee and David Peace and a number of other English writers, that seem to circle the same world, a blue-lit, tremulous world of secrets and illicit comingling of the upper and lower classes in Britain. But it also affects Northern Ireland. There is a strange, fetishistic nocturnal world there. Post-war Britain, just before the 60s break, that is very, very interesting. I don’t know why, but it is. I don’t know if these writers communicate. There is something going on there.

Order your copy of Poguemahone here!

Biblioasis is thrilled to share that last night, on Thursday, June 9 at 6:30PM EST, it was announced by the Atlantic Book Awards that Chemical Valley by David Huebert won the Alistair MacLeod Prize for Short Fiction!

Biblioasis is thrilled to share that last night, on Thursday, June 9 at 6:30PM EST, it was announced by the Atlantic Book Awards that Chemical Valley by David Huebert won the Alistair MacLeod Prize for Short Fiction!