How a Poet Must: On the passing of Steven Heighton

It was with great shock and sadness that I learned of the passing last evening of Steven Heighton. We knew that he was ill, though we hadn’t for long. We were certain that he—and we—had more time. His partner Ginger Pharand called it “a forest fire of an illness,” and so it must have been. On February 17 he wrote to say that he’d “just been back from the hospital: barium smoothie and a 12 minute x-ray. It was surprisingly fun. It’s a merry crew in the imaging department.” You can hear Steve’s usual spirit, playful even in the midst of anxiety. When I inquired about his health he said that there was little to worry about, that the x-ray indicated that there was nothing life-menacing causing the pain he’d been living with. On antibiotics, he was looking forward to a month without weed or alcohol. We found out later that it was indeed life-menacing, but the prognosis still gave him a year, perhaps longer. If anyone was going to defy such a prognosis, wouldn’t it have been Steve? He was, if not quite youthful, then ageless.

I didn’t get a lot of time in his presence. We ran into each other here and there over the years, at festivals, events, once at the Ottawa ceremony for the Governor General’s Award, the only time I ever saw him in a suit. When we launched his Reaching Mithymna: Among the Volunteers and Refugees on Lesvos we were in the middle of the pandemic, and the launch and even the Weston Writers’ Trust ceremony, after the book was nominated for the organization’s nonfiction prize, were virtual. It was a disappointment, not being able to get together with him to celebrate Reaching Mithymna, but we had other books, there would be other times. We’d met the first time a little more than 20 years ago, before Biblioasis existed as a press, when I invited him to Bookfest Windsor in support of his new novel, The Shadow Boxer. At the afterparty in his Al Purdy shirt—there’s a fine essay here on his relationship to that piece of clothing—black jeans and some sort of cowboy boots (though perhaps my memory is playing tricks), he looked to me like some kind of earnest punk, by which I mean to pay him the highest compliment: think of a slightly older Joe Strummer. He could certainly be mischievous—and we got up to some hijinx that night, playing a prank on a former schoolmate of his turned professor who had since Steve last knew him acquired a British accent—but it was a gentle brand of mischief, one that took a great deal of joy in the absurdity of the world, and of the literary world in particular. He was humble, self-deprecating, and obviously interested in everything, and in everyone, surrounding him. Care, concern, emanated. There are those writers, and we all know who they are, who work to keep the spotlight on themselves at all costs; others, far more rare, willing to divert that light elsewhere: Steven for me is one of only a handful of the latter.

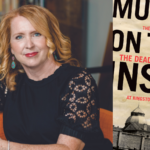

If he was ageless, it was because of these qualities: he hadn’t hardened yet into any encrusted position. Being humble, he was still too curious about the world, willing to learn, try new things, consistently aware of what he didn’t know, hence he remained a touch more malleable than some of his other age-sharpened peers. He worked successfully across a range of forms, poetry, short stories, novels, and music, one feeding and bleeding into the next. He worked at translation throughout his career (he called these mistranslations) to be closer to the poets he most admired, and his versions of Paul Celan, Arthur Rimbaud, Osip Mandelstam and others (all gathered in House of Anansi’s Selected Poems 1983-2020, which you can purchase here) opened their work to me for the first time: full-bodied and felt, there’s no typical translator distance with these poems. Celebrated as a novelist, I think he truly excelled in the shorter forms: he was one of our best poets, a masterful short story writer, a playful essayist. His first two short story collections, Flight Paths of the Emperor and On Earth as It Is, rank as among the strongest collections published in the last quarter of the previous century in this country; and 2012’s The Dead Are More Visible is quite easily one of the best of this century. It received universal praise: “The best stories in this book,” Jeet Heer wrote in the National Post, “are as good as the fiction of Alice Munro or Mavis Gallant. Or, to be more blunt, Heighton is as good a writer as Canada has ever produced”; “As good,” Mark Medley agreed in the Globe & Mail, “a short story writer as anyone not named Munro … The best (living) author never to have won a Giller Prize.” He was working on the edits to his next collection, Instructions for the Drowning (forthcoming, Biblioasis) when the forest fire struck: it causes me immeasurable sadness that he won’t be present to launch the book with us.

It’s a strange thing to develop a relationship with writers through publishing their books. There are these intense periods of daily, more than daily contact, for weeks, months, sometimes as much as a year; before a bit more distance enters, you hear from one another less frequently, having less reason to do so, until the next book, and the cycle begins to quicken again. What we were most looking forward to with Steven was the next book, and not only because it promised to be spectacular: it was to work with him, to have reason once again to be in even closer contact, to share jokes and asides and encouragement. To finally spend a bit more time with him, in our backyard or his, coffee or wine or whiskey as the occasion warranted. But also because the next book promised to be spectacular, sparking the missionary element of our vocation: with Instructions for the Drowning we were going to work our asses off to try and finally bring him the readership he deserved. As we will, being the least we can do, and what Steve deserves. So: if you’re reading this, go read him instead.

Steven Heighton made us better, as publishers, as people. I can see from the tributes that have met his passing we’re far from alone in this. He challenged and encouraged in equal measure, almost always getting the balance right. In this age of ironic detachment he risked being earnest, vulnerable, showing care and concern; “hardened against carious / words, spurious charms,” there was about him nothing counterfeit; he worked and worried about making the world a better place to be; worried about how he, and all of us, should move through it. And goddamn it is he going to be missed.

–Dan Wells

(Photo credit: Neal McQueen Photography)