The Bibliophile: Like working a piece of clay

Want to get new excerpts, musings, and more from The Bibliophile right away? Sign up for our weekly online newsletter here!

***

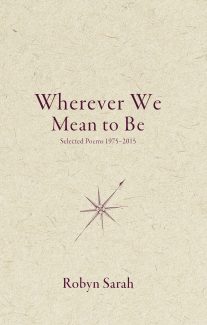

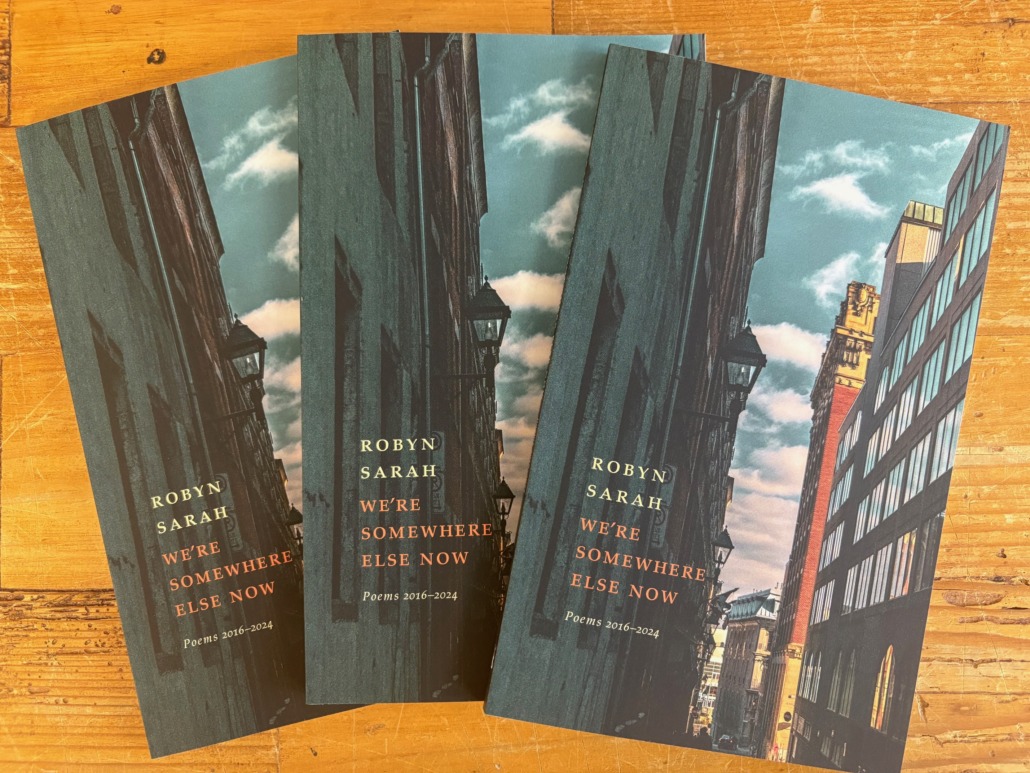

An interview with Robyn Sarah, author of We’re Somewhere Else Now

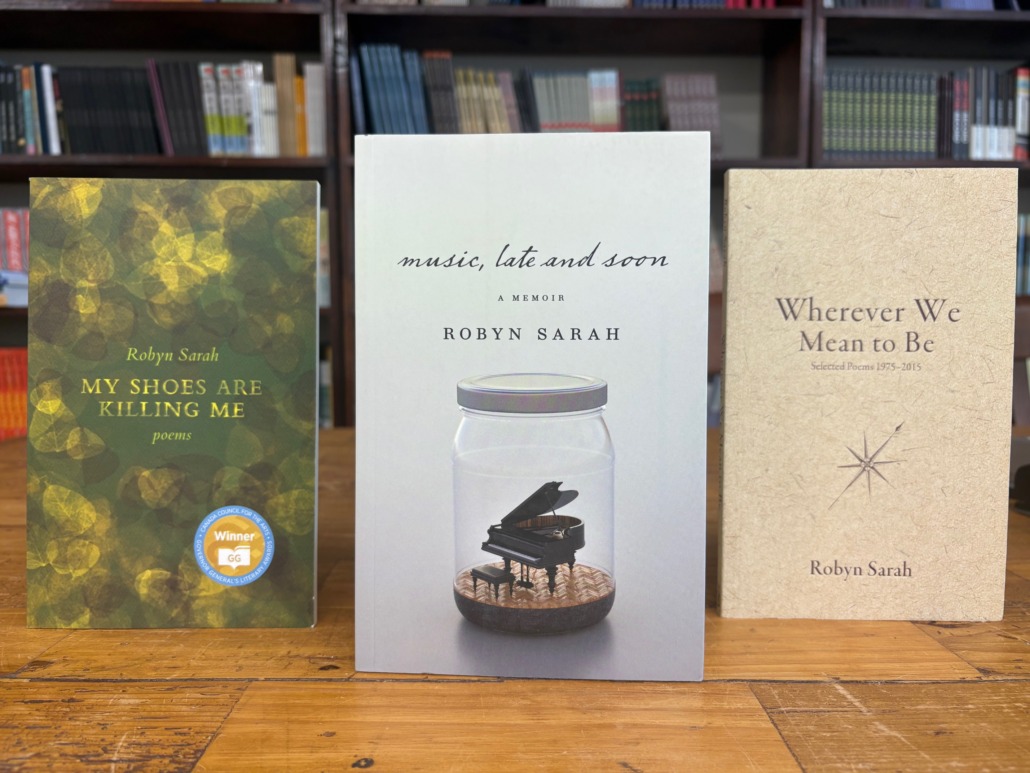

Robyn Sarah has been a household name among Canadian poets since before I started reading poetry, and it’s been a privilege to work (even in my small way) on her latest collection—her first book of new poems since 2015’s Governor General’s Award-winning My Shoes Are Killing Me (maybe one of my favourite titles of the century).

We’re Somewhere Else Now compiles poems written between 2016 and 2024, documenting the pandemic years with a quiet, lyric attentiveness. The poems are full of lovely—alternately foreboding and humour-tinged—imagery. One of my favourite images describes a high-rise apartment in the midst of lockdown: “balconies / stacked skyward like open bureau drawers.”

Another highlight of this book is the extended sequence poem, “In the Wilderness,” a poem that combines various forms and voices, a meditative yet playful unmooring of faith and “jam session with Doubt.”

I had the immense pleasure of asking Robyn a few questions about her work.

Thank you for reading,

Dominique

Publicity & Marketing Coordinator

A Biblioasis Interview with Robyn Sarah

It’s been ten years since your last poetry collection was published. In this time, your selected poems came out, and you wrote a music memoir. I wonder what you see as having changed (intentionally or not) in your poetry since My Shoes Are Killing Me? Have the experiences of writing a prose memoir and compiling a book of selected poems also altered your more recent poetic preoccupations?

I wouldn’t say that compiling a second selected in 2017 (the first was The Touchstone in 1992) altered anything in my poetic practice or preoccupations. Nor did working for close to a decade on an extended prose work—except in the sense that its completion freed me to write poems again, something I felt good and ready to do! The memoir was extremely demanding, and from 2016 until 2020 it took the place of poetry-writing almost entirely (though around 2018 I did begin scratching out fragments towards what would become the long mixed-genre poem in the new collection). I’ve always written both prose and poetry (first stories at the age of six, first poems at nine) and have also sometimes mixed them (there are prose poems in every collection I’ve published). Many reviewers have observed that my poetic practice and preoccupations have been remarkably consistent from one collection to the next (“stubbornly so,” as one put it).

Montreal is a consistent backdrop in We’re Somewhere Else Now. Early on in the book, the speaker is “buying a potted narcissus / at the Atwater Market,” and later on in the poems we get glimpses of intersections: Hutchison and Villeneuve, Parc and Villeneuve. I wonder how important a place—and specifically Montreal—is to your work?

Some writers find visiting new places indispensable to their creativity. I am not one. Travel is stimulating, but I find it very stressful and disruptive, so I minimize time away from home; I need stability in order to do creative work. I’ve lived in Montreal almost continuously since the age of four—that’s a lifespan—and have rarely left it for longer than a few weeks at a time. I watched the city grow and change as I grew and changed. If you live in a city for long enough, you don’t have to go somewhere else to find yourself in a new place: you see it become one again and again—for better or worse. The same with a street or neighbourhood, like the Mile-End block where I’ve lived (in four different flats) for more than forty years. The current view out my window overlays memories that go back forty years—not to mention memories passed on by immigrant grandparents who lived within blocks of here in the 1920s. I love this city and neighbourhood. You mention Villeneuve (referenced in poems set in 1981 and 2021). Villeneuve was the name we gave to a small press I co-founded in 1976—based at home, in a third-floor walkup on that street, and then in two successive flats around the corner on Hutchison. My kids grew up on this block—a two-minute walk to Mount Royal Park, a half-hour walk downtown along Avenue du Parc. Literary forbears also lived here: the poet A. M. Klein raised his family in the block above ours; Mordecai Richler apparently lived briefly on ours as a college student.

Your poetry collections are usually varied on a formal level, and this one is no exception. I’m curious to know how you approach form: does it happen intuitively, or do you set goals for yourself? Is there a form you’d like to attempt that you haven’t yet?

Hard to answer, because what begins intuitively can later become more goal-directed. (I’m almost entirely an intuitive writer, but at a certain point in the process, unconscious intentions become conscious and begin to direct my choices.) I don’t go about looking for new forms to attempt, like learning a new trick—it’s more like one day I become aware of the formal pattern of a poem I may have known and loved for years without noticing it was in a form, and I become intrigued by the form and am inspired to imitate it in a poem of my own. (I wrote my first villanelle without knowing that the form I was imitating had a name.) I rarely begin a poem with a form in mind, but my training as a classical musician has always had an influence on how I write: I like my poems to have a shape or pattern, even if they’re free verse. I start a poem usually with a few lines that come into my head from nowhere, lines I like the sound of, and I let the poem grow from there, shaping as I go along. It’s more like working a piece of clay than like trying to impose a template on the words: you could say I invent new forms, some looser and some more obviously formal. But really it’s like I let each poem find its own form—either it begins to fall into a particular traditional pattern or it evolves into a shape I create just for that poem.

The second half of We’re Somewhere Else Now comprises a long sequence poem, “In the Wilderness.” I’m interested to know about the evolution of this one: did you set out to write a long poem, or did the various pieces eventually come together? Although thematically cohesive, I was struck by the variations in form and tone throughout (for instance, the playful, shorter lines at the beginning of “The Fiddler” are enticingly opposed to other, almost prose-like sections).

The title poem in My Shoes Are Killing Me, which I called “a poem in nine movements,” was not a suite of individual poems but an extended single work, meant to be read continuously as one, even though its nine sections have individual titles. At eleven pages, it was the longest single poem I had ever written, and it gave me the idea I might consider doing something similar, perhaps even chapbook or book length, on a single theme that had begun to preoccupy me: the irony that in a world where a glut of information on any topic was available at the click of a mouse, the effect seemed to be not to advance us in knowledge but increasingly to cast all knowledge into doubt. I had in mind, vaguely, an extended text that would be philosophical in impulse, but not theoretical—not a treatise on doubt, but an inquiry with a human face, in layman’s language. How does the human being anchor itself at times when truths that have been our common ground for understanding the world begin to break down? The poem evolved very slowly; for two years there was no poem at all, just an accumulating body of disjointed fragments (ranging from a few lines to the equivalent of a paragraph or two, sometimes prose, sometimes free verse) scribbled by hand and eventually filling the equivalent of a Hilroy notebook, mixed in with other jottings and failed poem starts. This was not at all how “My Shoes Are Killing Me” had begun. I had no clear sense of what I was doing or how to work with this material, and no confidence that it would ever amount to anything. But I had to start somewhere, so at some point I began transcribing the “doubt” fragments onto the computer in a single long document, in the order in which they were written, separated by asterisks. Each time I reopened the file to enter the next batch, I would find myself beginning to “ work” one or more of the fragments already entered—letting them grow in stages, sometimes to merge with other fragments, sometimes to incorporate and dialogue with quotations from literature, scripture, prayer, popular song, film, and other sources. Sometimes I moved them around as I saw sub-themes begin to emerge. I wanted the segments, in the voice of a lone speaker, cumulatively to enact the sometimes chaotic thought processes of humanity cast adrift from its moorings as technology pulls familiar ground out from under the world we once knew, erasing landmarks and disrupting our belief systems. I wanted this text to sound and feel improvisatory, like “thinking aloud” in real time—a sort of ad-lib soliloquy with starts and stops and rough edges—not like polished poetry. Hence the variability—moving back and forth between prose and verse, sometimes within the same segment; different line lengths and stanza patterns, different vocal registers and tonal shifts.

Your book is filled with questions. These often seem to point out, or dismantle, the absurdity of human logic: “Why put a name on a day? / How can it matter what a day is called? / The cat doesn’t know it’s Tuesday.” What do questions mean to your work? What do you think they contribute to a poem that a statement might lack?

Many readers have remarked that my memoir, too, is filled with questions. I’m not necessarily looking for answers. I think questions are my “way in” to something I wonder about and would like to explore. I’m a wonderer. Even when I don’t voice them in so many words, I think the impulse to poetry comes to me as a question. It can be directed to the poem’s subject or addressee, or it can be a question I ask myself. It may be a “question arising” from the poem or implied by it, left to linger unanswered. Questions invite a reader’s involvement. A question opens the way to thinking about something, where an answer or a statement tends to close it.

As a final question, I’m curious to know who your great poetry loves are. While writing this book, but also more generally—who are the poets who’ve guided you in your own work over the years? I might guess Gerard Manley Hopkins, for one, from the appearance of some of his lines in this collection . . .

Single poems encountered at the right moment, by poets I might not otherwise consider “great poetry loves,” have inspired many of my poems. Different “loved poets” have guided or influenced me at different times, and there have been so many. Generally, in my early high school years the poets I loved were A. E. Housman, Edna St Vincent Millay, and Walt Whitman; in my late teens and early twenties it was primarily T. S. Eliot, Robert Frost, and Wallace Stevens, but also Emily Dickinson, Robinson Jeffers, Theodore Roethke, Dylan Thomas, Conrad Aiken, Wilfred Owen, more ambivalently William Carlos Williams, Marianne Moore . . . . Well, I could go on. Donne and Herbert and Hopkins. Philip Larkin was a later discovery, I don’t know how I missed him before. Of contemporary Canadian poets, I have especially loved the poems of George Johnston, Margaret Avison, and Don Coles. Along the way I’ve also read poetry in translation and have been inspired by poems originally written in French, Latin, modern Greek, modern Hebrew, Italian, Spanish, German, Russian, Polish, Swedish, and Chinese.

In good publicity news:

- The Sorrow of Angels by Jón Kalman Stefánsson (trans. Philip Roughton) was reviewed in Kirkus Reviews: “‘Some books are essential, others diversions,’ the boy thinks to himself. This book belongs in the former category.”

- Precarious: The Lives of Migrant Workers by Marcello Di Cintio appeared on CBC Books’ Fall Book Preview: “Di Cintio investigates . . . and questions whether a system that relies on the vulnerability of its most marginalized can ever be made more just.”

- Voices of Resistance: Diaries of Genocide was reviewed in several outlets recently, including:

- Asymptote: “As long as these powerful voices continue to speak to us, we—and anyone with the power to stop this ongoing genocide—will repay them with our listening.”

- Arab Lit Quarterly: “Their words go beyond the frame . . . [and] requires of the reader an emotional strength to see Gaza in depth, to follow day by day—or for as long the genocide allows them to write—the thoughts of Batool, Sondos, Nahil and Ala’a.”

- The New Arab: “The artistry and creativity displayed by these four remarkable women both astonish and humble readers . . . Instead of cold numbers and abstract political jargon, these pages offer irrefutable proof of lives lived and spirits tired, but unbroken.”

- Ira Wells, author of On Book Banning, was mentioned in the Guardian’s and the Globe and Mail’s articles on Alberta book bans.

- Elise Levine, author of Big of You, was interviewed about her short story collection in The Ex-Puritan.

- Benbecula by Graeme Macrae Burnet was featured in Publishers Weekly’s article on Big Indie Books of Fall 2025.