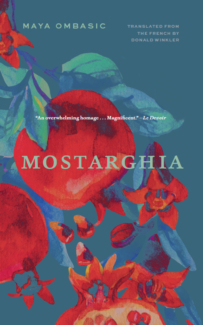

Happy U.S. Publication Date, MOSTARGHIA!

U.S. Readers: The Wait Is Over!

Donald Winkler’s English translation of Maya Ombasic’s Mostarghia, a moving memoir of refugee experience and filial love, is available today in U.S. bookstores.

AN OPENCANADA SUMMER READ 2019

In the south of Bosnia and Herzegovina lies Mostar, a medieval town on the banks of the emerald Neretva, which flows from the “valley of sugared trees” through sunny hills to reach the Adriatic Sea. This idyllic locale is the scene of Maya Ombasic’s childhood—until civil war breaks out in Yugoslavia and the bombs begin to fall. Her family is exiled to Switzerland, and after a brief return, they leave again for Canada. While Maya adapts to their new home, her father never does, refusing even to learn the language of his new country.

A portmanteau of Mostar and nostalgia, Mostarghia evokes Ombasic’s yearning for a place that no longer exists: the city before the civil war, when its many ethnicities interacted in a spirit of civility and in harmony. It refers as well to Andrei Tarkovsky’s classic film Nostalghia, the viewing of which illuminated the author’s often explosive relationship with her father, a larger-than-life figure who was both influence and psychological burden: he inspired her interest, and eventual career, in philosophy, and she was his translator, his support, his obsession. Along with this portrait of a man described by turns as passionate, endearing, maddening, and suffocating, Ombasic deftly constructs a moving personal account of what it means to be a refugee and how a generation learns to thrive despite the struggles of its predecessors.

Praise for Mostarghia

“Fascinating and timely…anybody who wants to think deeply about what happens when people are forced to leave their homelands will want to pick this book up.” —Book Riot

“Intimate, a filial cri de cœur…The book is run through with dark humour, and some of the most fatalistic scenes are also wryly funny…The condition of nostalgia is both dissociative and cleaving, and it is this tension that Ombasic most adeptly conveys.” —Montreal Review of Books

“Strikes a great balance between the ebb and flow between unemotional observations that provide context for the lasting divides in the Balkans, and a humanization of the victims of conflict….[Ombasic writes] with a tender care that evokes a sadness mixed with levity, anger mixed with love.” —The Walleye

“After her father dies, Ombasic seeks to resolve all that was unresolved between them in life. Her memoir ripples with the tension of these two great hearts each trying to shoulder an outsized burden… Subtly and with lyricism, Ombasic unpacks her father’s role in her history alongside the role of their hometown, Mostar, not to mention the Balkans, religion, communism, war, displacement, and nostalgia.” —Foreword Reviews (starred review)

“With great candor, Ombasic shares how her experience as a refugee differed from her father’s…Through beautiful prose and impressive attention to detail, Ombasic paints a loving yet honest portrait of her father in all his complexity.” —OpenCanada

“An overwhelming homage, clear-eyed and drenched in tenderness, Mostarghia is driven by Maya Ombasić’s strong, sensitive voice, which allows us to glimpse the reverse side of the shadow of exile. Magnificent.” –Le Devoir (Montreal)

“In an unadorned style, which contains emotion by restricting itself to facts, the author recounts her years during the war, then her exile in Switzerland, then Canada. The book’s strength stems in large part from its ability to show the concrete daily consequences of a war from which the family suffers without participating in it directly, to showcase the absurdity of the issues–ethnic, religious, territorial–from which children and parents feel themselves estranged.” –Le Monde (Paris)

“The book, its title inspired by Andrei Tarkovsky’s film Nostalghia, is a daughter’s love song to her father and the tale of her salvation, her refusal to be defeated by depression in order to move on.” –l’Humanité (Paris)