The Bibliophile: The wonders we can create

Want to get new excerpts, musings, and more from The Bibliophile right away? Sign up for our weekly online newsletter here!

***

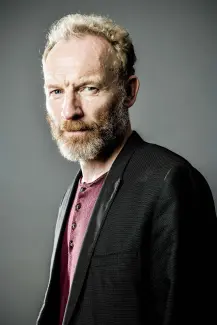

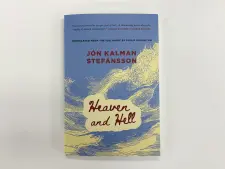

In anticipation of Heaven and Hell’s pub date this Tuesday, we’re following up last week’s excerpt with an interview with Icelandic author Jón Kalman Stefánsson, conducted by publicist and all-star interviewer Dominique.

On another note, if you have any thoughts on what you might like to see in a future Bibliophile—the behind-the-scenes of book publishing, features on backlist or frontlist books, whatever you’re curious about—feel free to reach out and let us know! We want to know what you most want to read about.

Ashley Van Elswyk

Editorial Assistant

***

A Biblioasis Interview with Jón Kalman Stefánsson

Heaven and Hell is a testament to the power of literature: tragedy strikes because of poetry, but the boy is also able to find a reason to carry on because of books—in returning the Milton to its original owner and in the company of readers he finds once he arrives. Can you tell us a bit about how books, as well as the friendships and communities that form around books, have changed your life or given you hope?

I was, as a child and a teenager, an eager reader, and for me libraries were places of wonder, adventure, and shelter. I think I was what we could call a born reader: it’s in my blood, the love for literature, this hunger, need, for the worlds and the wonders we can create and find in words. Books were for me both, at perhaps the same time, some kind of get-away transport, and something that enlarged my life and my thoughts. And I believe that one of the main purposes of literature is namely to do all that: enlarge our life, help us to forget our self, make us see the world and our own lives in a new, often unexpected light, help us to travel around the world, get to know other times, different cultures, ideas. Those who read a lot of books, both fiction and non-fiction, and of course poetry, from all over the world, are the only ones who truly can be called cosmopolitans. And those who read little, and perhaps never foreign literature, can be easy prey for populist politicians who get their power from prejudice, discrimination, hatred and fear for those who are slightly different from them; politicians who want us to fear variety, instead of embracing it as we should do.

It’s been a while since Heaven and Hell was originally published in Iceland. Has your relationship to this work changed since the beginning? What does it mean to you now, considering the scope of your work?

Yes, I wrote Heaven and Hell almost twenty years ago, so many things have changed since then: both in my own life and in the world. The book is the first one in a trilogy, and the next two came out in 2009 and 2011, so these worlds travelled inside me for around six years. Since then, I’ve written six novels, and I think that one changes—hopefully—a bit with every book one writes. I have to admit that I seldom think of my older books: they just are there, living their own lives, and have no need for me anymore. They are part of me, but they are at the same time totally independent every time they meet a new reader. I’m fond of them, glad if they are doing well, and hope that they’ll change or affect the lives and thoughts of the readers.

A stack of Heaven and Hell by Jón Kalman Stefansson, translated by Philip Roughton. Photo courtesy of our Biblioasis Bookshop staff.

A lot about this book reminded me of epic poetry—the movement of the language (the plentiful, rhythmic use of commas, the repetition of “I am nothing, without thee”), the “hero’s journey” at the center of the book. How important is poetry to your prose writing? Are there any particular poets whose influence you see in your writing?

Poetry is very important to me; I started my writing career as a poet, published three books of poetry before I turned over to prose. In a way, I think that I use, though subconsciously, the technique and the inner thinking of poetry while writing prose; therefore, poetry lies in the veins of my prose. I think as a poet while writing as a novelist. I also see my novels partly as a piece of music, a symphony, a requiem, a rock or hip-hop song. There lies so much music, both in the language and the novel itself: its structure, style, breath. And the structure is for me just as important as the stories; one can sometimes call it one of the characters.

A lot of poets have influenced me throughout time. I read poetry constantly, and never travel without having some books of poetry with me. They can be Icelandic, European, South or North American, Asian . . . and from all time periods. I guess that poets like Vallejo, Szymborska, Borges, Tranströmer, Zagajewski and many more have influenced or inspired me; the same goes for lyrical novelists, like, for example, José Saramago and Knut Hamsun.

I like the coexistence, in the lives of your characters, of the physically rigorous and the intellectual. These characters are in a constant struggle against the elements, but many of them are simultaneously leading these rich, bookish lives. And the books they read (Paradise Lost, for example) seem far less escapist than immersive—like an extra set of eyes over the world. How important is the natural world to the intellectual world of books, and vice versa, in your work?

Books have in my view always been part of life, the world; not something sidelong, but flowing through life, affecting it. We sometimes forget that some of the most famous persons in world history are characters in books, novels: Raskolnikov in Crime and Punishment; Don Quixote; Achilles; Oliver Twist; Anne Karenina . . . People who read novels are constantly meeting new people, new characters, who affect them, influence them, move them with their thoughts, words, destiny, in short: become part of their life, their inner world. I sometimes say that what we call reality and then fiction/literature are like a couple dancing together; and occasionally the dance becomes so intense, that they seem to almost melt together and then it’s impossible to see which is which. Therefore: literature reflects life, and life reflects literature.

I think I was what we could call a born reader: it’s in my blood, the love for literature, this hunger, need, for the worlds and the wonders we can create and find in words.

I was in a class once in university where the professor would have us make a playlist for every book we read. I liked that idea, and still find myself doing it. I know that music is very important to you—you created Death’s Playlist for Your Absence Is Darkness, and you’ve written a book about The Beatles. I’m not asking you to create an entire playlist for Heaven and Hell, but does this book (or the trilogy as a whole) evoke any particular songs for you?

Seems to me that this professor did a good job; a wonderful idea! Yes, music is very important for me. I love making playlists, for myself, for my wife and I, my friends, my kids, who influence me all the time by playing for me the music they are listening to. I’m always eager to get to know new artists, both those who are contemporaneous to us, in hip-hop, rock, jazz, classical, and then also getting to know artists and composers from the past. And my novels are often filled with music, references to music, songs that characters are listening to, or it simply comes to my mind while writing, forcing itself into the story, becoming part of it. I’m not sure that there were any particular songs linked to Heaven and Hell, but I think that my running songs from that time—I’m a runner and I always have a special song list for my runs—and while running, my thoughts about the novel I’m working on at that time flow around in me, mixing with the songs, which sometimes affect or create new ideas. And my running songs from that period were for example songs like Jesus of the Moon by Nick Cave; Where is My Mind by Pixies, Back to Black by Amy Winehouse; but while working on the novel songs like Falla by Nana, Aria from Pastorale in F Major by Bach, both played by the great Pablo Casals, and Gnossiennes by Satie; and I guess that the atmosphere of that music coloured, in one way or another, what I was writing, and how.

And we ask this every time, but I always love hearing the answer—what are you reading and enjoying right now?

I’m usually reading many books at the same time, and right now I could name: Human Acts by Han Kang; The Gospel According to Jesus Christ by José Saramago, one of those authors who has followed me for a long time; I’m reading this book for the second time because I read it in Danish some fifteen years ago, and was very taken by it then. It’s great to read it again, but I’m afraid that I’m a bit more critical towards this fine novel now; Urd by a Norwegian poet, Ruth Lillegraven, a strong, fascinating book of poetry telling a story of two women across different periods of time; The Confessions of Augustine of Hippo, written about 400 AD, a book that has influenced our way of thinking, if not feeling, regrettably in some ways; and then always some books of poetry: Szymborska, Werner Aspenström, a great Swedish poet, and the poems of Enheduanna, the earliest known name in world history, from around 2280 BC, who wrote her poems almost 1500 years before the first letter was drawn in the Old Testament.

***

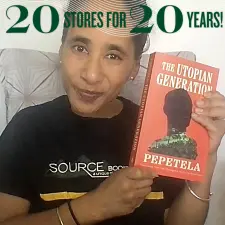

20 Stores for 20 Years: Source Booksellers

After a brief hiatus, we’re starting up our 20 bookstores to celebrate 20 years of publishing posts again! Today, we’d like to celebrate our neighbours in Detroit: Source Booksellers. Owner Janet Webster-Jones spent 40 years as an educator in Detroit public schools before she set up Source’s brick and mortar location in 2002. Janet now runs the store alongside her daughter Alyson, and they are a midtown institution! Read on for why our publisher Dan loves Source, and why Alyson chose The Utopian Generation by Pepetela (trans. David Brookshaw) as her favorite Biblioasis book.

Biblioasis publisher Dan Wells poses with Source Booksellers’ Alyson Turner and Janet Webster-Jones.

Dan on Source Books: I’m not sure there’s a bookseller I admire more than Janet Jones at Source. Whenever I’m feeling exhausted by the state of the world, or the state of the industry, I take inspiration from her example. Now well into her ninth decade, she remains a veritable fount of inspiration, joy, enthusiasm and love, for books, literature, and for her Cass Corridor community. Alongside her daughter, Alyson, a very fine and energetic bookseller in her own right, Source is set to remain an inspiration for years to come.

And here’s why Alyson chose The Utopian Generation: “My heart landed on celebrating the creative and brave translated novels we get from Biblioasis. Yes the Canada Reads ’24 winner in French, The Future, which rethinks Detroit, MI, is a delight to read and sell. Yet another recent release that is hard to put down, The Utopian Generation gives us a peek into an African struggle for decolonization. Bravo to Biblioasis for Twenty Years of indie publishing just across the river!!!!”

***

In good publicity news:

- The Notebook by Roland Allen was reviewed in the New Criterion: “Fascinating . . . [a] wide-ranging and well-researched book.”

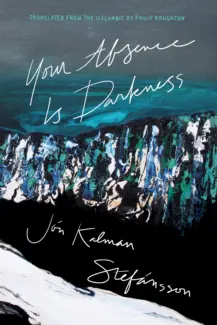

- Your Absence is Darkness by Jón Kalman Stefánsson (trans. Philip Roughton) was reviewed in The Scandinavia Review: “[An] epic story of love, legacy and grief.”