IN CONVERSATION: with Pino Coluccio

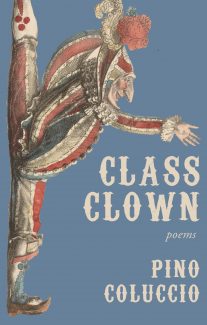

We’re thrilled to finally share the news that Pino Coluccio’s Class Clown has been named a finalist for the 2018 Trillium Book Award for Poetry! The award is given annually to a first, second, or third book by a new or emerging poet. Pino’s collection is one of three finalists for the $10,000 prize, the winner of which will be announced June 21.

We couldn’t be more pleased for Pino, whose work has been described by CBC Sunday Edition’s Michael Enright as “short, witty poems about love, death, and the absurdities of modern life … I kept going back to it over and over and over again.” While we wait for the cool days of mid-June (seriously who turned up the sun omg), please enjoy this interview with our favourite class clown. Laughing makes you feel cooler, you know …

A Biblioasis Interview with Pino Coluccio, author of Class Clown.

But seriously…

What do you want readers to know about you? What are your interests outside of poetry?

What do I want readers to know about me? Honestly, as little as possible (laughs). I don’t want no strangers all up in my business.

My interests outside of poetry? They come and go but right now, my job, TV, occasional movies or streams of old favourites. Youtube, Time travel, the 80s. All kinds of music but especially rock.

Languages – I make a point of reading the news in French and Italian as well as English and am currently learning German. But most of this stuff I do in half-asleep dribs and drabs. I spend most of my time at work or recovering from work.

There is occasional resistance/snobbery in contemporary poetry to things like meter, rhyme, capitalization, punctuation, etc. Can you talk a bit about your formal choices in your poems? Do you make these choices before you set out to write a poem (or a collection) or do you simply write what feels right for the work?

I don’t make a whole lot of choices during the initial writing stage. Things will occasionally just hit me, and they pretty much always hit me in meter. I sort of set myself to meter back in my 20s and things just come out that way now. I suppose that was a choice — setting myself to meter. I think I did that on the recommendation of a professor I had for a creative writing course I took, and also in imitation of Seamus Heaney, who I worshipped at the time. Plus, my Italian wasn’t so good back then, so when I read Italian poetry, I didn’t always understand what the heck it meant, but if it rhymed and scanned, I got enjoyment out of it that way, just by the patterns of sound, and decided similarly pleasurable patterns of sound would be good to include in my own work.

I think rhyme and meter make poetry more exuberant and entertaining, more like rock music, and so I keep myself set that way and things come out in meter. And then where choice comes in is when I revise, but that’s just changing words or stanzas, not usually the whole form or style of the poem.

Can you discuss the importance of humour in your writing? Do you think you see the world differently than some writers because you come to writing through a lens of humour?

Ain’t nobody got time for other people’s problems. But make people laugh and they just might stick around. But seriously, I kind of just stumbled into the humour thing, to be honest. People seemed to find some of my first book funny and seemed to like that about it, and so I decided to make that my thing. I was actually trying really hard to be grand and tragic in my first book (laughs). But then it dawned on me, the tragedy market is already saturated and other people do it better. If I move into comedy I’ll have way less competition. Plus, all the TV shows and movies I watch are comedies, I like humour, why act all tragic in my poems? I like rock and it’s fun and lively. Why not write rock poetry?

That said, I don’t think much of what I write is, in the true sense of the term, light verse. Marcus Bales, a poet out of the US, says he tries to be light but not merely light, serious but not merely serious. I really like that, that seriousness can be mere too, and that one should be merely neither. I like to put it this way: it’s not me who’s light, it’s other people who are overweight.

The way I see it, there’s three schools of thought. The “life sucks and isn’t that just terrible” school. The “life does NOT suck, it’s perfectly goddamn wonderful” school. And the “life definitely totally 100% does suck but I ain’t gonna let that stand in the way of me having a good time” school. You can guess which one I’m enrolled in.

What can people do to see more poetry in their day-to-day lives? To find more humour in them?

The absolute 100% best way to see more poetry in your day-to-day life is to read more Philip Larkin, trust me on this one. And to find more humour in your life, watch SCTV, anything by Christopher Guest, Seinfeld, Borat, The US Office, Curb Your Enthusiasm, Peep Show and just about anything by Woody Allen.

In “Poets” the poetic voice seems to be somewhat…critical about how seriously other poets take themselves, and in “Manifesto” the poem ponders the difference in status between “the fiddler” and “the violinist.” This comparison continues with the between “brew” and “vino” before ending on “not a poet/ but a Pino.” Am I correct in assuming that you’re aligning yourself here with the fiddler and the brew over the violinist and the vino? Is there an aim in your writing to strip away the pomp and get down to the honesty behind poetry?

Well, I’m a fiddler around violinists and a violinist around fiddlers (laughs). But where I was going with that poem is, categories don’t matter, just be yourself and do what honestly gives you pleasure, and to heck with people who say you’re a Philistine or boor or what-have-you.

Some of your poems in Class Clown are based upon writing or stories of Italian writers and performers. Corrado Govoni, Giovanni Pascoli, Domenico Modugno all feature. How does your Italian heritage influence your work or your world view? What draws you specifically to the writers you’ve acknowledged in Class Clown? Are there others of particular importance you would like to mention?

There’s only a handful of Italian poets I’ve read very much of, whole books as opposed to just anthology pieces, Leopardi, Pascoli, Guido Gozzano and Montale. The rest I either find too difficult, like Dante, or I understand them but just don’t like them. So, the poems I adapt in the book are just ones I understand and like. The Govoni I came across in an anthology and easily got and liked. And Modugno is actually a singer – “Volare” is the hit he’s most known for. But “Vecchio Frack” is true poetry, very mysterious, deep and haunting. Plus it’s from my parents’ era so it’s sort of a nod to them. “Benedizione” I first read years ago and it’s stayed with me ever since. A poem I both fully get and truly love. My adaptation of it was inspired by a real priest, Don Augusto, and a pious Italian Catholic girl I met here in Toronto, named Francesca.

I should also mention that I get a lot of inspiration from Neapolitan dialect poets – Libero Bovio, Ferdinando Russo, Rocco Galdieri, Eduardo de Filippo, Edoardo Nicolardi, Armando Gill and Salvatore Di Giacomo to name a few. And for that matter from Neapolitan music and from the actors Toto’ and Massimo Troisi.

My background has for sure had a huge impact on my worldview – whose hasn’t – and Italian culture in general inspires me, gives me models to aspire to and feeds my imagination – gives me ideas, images, details and subjects, the more so because I see Italian culture as legitimately my own, a mighty trunk I’m a tiny twig on a branch of, as opposed to something foreign just randomly borrowed.

Overall, my work has been way more influenced by British, Irish and American poets than by Italian ones. Which only makes sense since, after all, I’m writing in English. Who better to learn the ropes from than fellow English-language poets? The two languages and their respective poetic traditions are much different from each other — more so than, say, Italian and French or English and German. So, there’s not much overlap or much that’s transferable from the one to the other. So, if I’m going to write in English I kind of have to base myself on English examples.

There’s something an Italian-Canadian girl I once knew said that’s always stuck with me: “I think in English, but I feel in Italian.”

Well, one thing I definitely got from Italy is my “life sucks but have fun anyway” attitude. Italy is, after all, the country that, though beaten to a pulp dozens of times by all manner of foreign powers (not to mention Popes, plagues, earthquakes and Madonna), nevertheless managed to invent like 400 different shapes of pasta.