News & Awards: THE FUTURE, THE ART OF LIBROMANCY, CONFESSIONS WITH KEITH, and more!

The Future by Catherine Leroux trans. Susan Ouriou (Sep 5, 2023) was reviewed in the Toronto Star. The review was published August 31st, 2023. You can read the full review here.

Alex Good writes of this post-dystopian novel,

“What makes The Future hopeful is its imagining of new, organic, co-operative (but not egalitarian) communities … savage but caring networks: small, local, and while living close to the edge still managing to get by. It may not be progress, but it is adapting to a vision of the future that hits pretty close to home.”

The Future was also featured in Kirkus Reviews as one of “Eight Big New Fiction Books from Small Presses.” The article was published online on September 6, 2023. You can read the full article here.

Catherine Leroux was interviewed by Nantali Indongo for the CBC Montreal arts and culture program The Bridge on August 26th, 2023. They discussed climate anxiety, dystopian and post-dystopian science fiction, parenting young kids, and what Catherine calls her “writing face”. The one hour interview is available on demand from CBC Radio here.

The Future has also been named by CBC Books to a list of Fiction Titles to Read for Fall 2023, which was published on August 31st, 2023. Read the list of anticipated fiction titles here.

Get The Future here!

THE FULL-MOON WHALING CHRONICLES

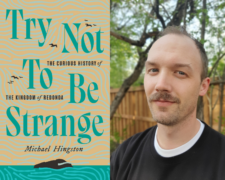

Jason Guriel, author of The Full-Moon Whaling Chronicles (August 1, 2023) has been interviewed in the Globe and Mail. The interview was published on August 31, 2023.

You can read the full interview here.

Get The Full-Moon Whaling Chronicles here!

Standing Heavy by GauZ’, trans. by Frank Wynne (October 3, 2023) was listed in The Walrus as one of the “Best Books of Fall 2023.” The article was online September 8, 2023. You can read the full article here.

The Walrus calls it:

“A spry volume of 167 pages … that manages to trade heavily in politics while also sneaking up on your sympathy. I won’t spoil the end, but it startled me in its poignancy.”

Order Standing Heavy here!

The Art of Libromancy by Josh Cook (Aug 22, 2023) was reviewed in the Winnipeg Free Press. The review was published online on September 2, 2023. You can read the full review here.

Ron Robinson writes,

“He writes as a fan of thesis, antithesis, synthesis — looking for solutions.”

The Art of Libromancy was also reviewed in That Shakespearean Rag by Steven Beattie. The review was published online on September 5, 2023. You can read the full review here.

Beattie writes,

“In pulling back the curtain to show readers the nuts and bolts of what this entails, Cook has provided a valuable service.”

Josh Cook was interviewed on the Book Storm podcast. The interview was published online on September 5, 2023. You can listen to the full episode here.

Get The Art of Libromancy here!

Breaking and Entering by Don Gillmor (August 15, 2023) has been reviewed in the Winnipeg Free Press. The review was published online on Sept 2, 2023. You can read the full review here.

Andrea Greary writes,

“Gillmor is a skilled writer.”

Get Breaking and Entering here!

Confessions with Keith by Pauline Holdstock has been shortlisted for the 2023 Victoria Butler Book Prize! The shortlist was announced on September 7, 2023.

Check out the full shortlist here.

Get Confessions with Keith here!

Big Men Fear Me by Mark Bourrie and On Browsing by Jason Guriel were both nominated for the 2023 Heritage Toronto Book Award! The nominees were announced on September 5, 2023.

Check out the full list here.

Get Big Men Fear Me here!

Get On Browsing here!