IN THE NEWS!

A GHOST IN THE THROAT

On Tuesday, May 25, 2021, Doireann Ní Ghríofa’s A Ghost in the Throat received a rave review in The New York Times! The review was published online, and was in the print issue on May 26, 2021. You can read it on their website here.

On Tuesday, May 25, 2021, Doireann Ní Ghríofa’s A Ghost in the Throat received a rave review in The New York Times! The review was published online, and was in the print issue on May 26, 2021. You can read it on their website here.

Reviewer Parul Sehgal wrote,

“The ardent, shape-shifting A Ghost in the Throat is Ní Ghríofa’s offering … She pieces together Ní Chonaill’s life as if she is darning a hem, keeping the story from unraveling further. She interrupts herself to stuff a child into a car seat, wrestle a duvet into its cover, pick pieces of pasta off the floor … What is this ecstasy of self-abnegation, what are its costs? She documents this tendency without shame or fear but with curiosity, even amusement … The real woman Ní Ghríofa summons forth is herself.”

And we’re thrilled that A Ghost in the Throat also received a second rave review in The New York Times! The review was published online on June 1, and it will be in a print issue this week. You can read it on their website here.

Reviewer Nina Maclaughlin wrote,

“A powerful, bewitching blend of memoir and literary investigation … Ní Ghríofa is deeply attuned to the gaps, silences and mysteries in women’s lives, and the book reveals, perhaps above all else, how we absorb what we love—a child, a lover, a poem—and how it changes us from the inside out … This is not dusty scholarship but a work of passion. ‘Raw’ is not the right word; the book is finely structured, its pace controlled. ‘Vulnerable’ gets closer, in its root force: vulnus, or wound. This book comes from the body, from the ‘entwining strands of female voices that were carried in female bodies.’ The sound of the female voice, the aural texture of A Ghost in the Throat, is part of its deep pleasure.”

A Ghost in the Throat was also reviewed in New York Magazine‘s weekly literary newsletter for Vulture, “Read Like the Wind”. The newsletter was emailed out on June 1, 2021. You can read the review here.

Reviewer Molly Young wrote,

“A Ghost in the Throat is a thrilling voyage into the lore of Ireland, motherhood, marriage, blood, and guts … Ghríofa assembles a cache of information on Eibhlín Dubh, composing her translation during minutes stolen away from domestic tasks. This is both a page-turner and a raw but erudite expression of a totally unique consciousness.”

Doireann Ní Ghríofa did an interview about A Ghost in the Throat with Between the Covers, a literary radio show and podcast hosted by David Naimon (produced by Tin House and KBOO 90.7FM community radio in Portland, Oregon). Her interview was released on June 1, 2021. You can listen to the episode on their website here.

Here’s what David Naimon had to say:

“A Ghost in the Throat is wonderfully hard to categorize: a memoir, a work of historical fiction, an autofiction, a translation, a book about translation, a book about poetry, a book that is poetry. It is all of these things and yet reads less like a work of avant-garde literary experiment and more like a detective or adventure story, an act of literary archaeology, a love letter, and a reclamation against the erasure of women’s lives and women’s art.”

The Paris Review published a wonderful, thoughtful review with Doireann Ní Ghríofa about A Ghost in the Throat. Rhian Sasseen, the Engagement Editor at Paris Review, spoke to Doireann about her writing, the mischief of translation, and the importance of elevating women’s voices. The interview was published on their website on June 2, 2021. You can read it here.

Here’s a highlight from one of Doireann Ní Ghríofa’s responses:

“It’s only as we progress through a life in art, or a life in literature, that we begin to understand what our core concerns are, and history is the throbbing pulse of my work as an artist. In all of my books, in all of my poems, I return again and again to our sense of the past and what questions the past is asking of us, and the ways in which we attempt to answer those questions, just by being who we are in the environments we’re born to.”

And finally, Doireann Ní Ghríofa was interviewed on Across the Pond, the literary podcast hosted by Texas indie bookstore owner Lori Feathers and UK publisher Sam Jordison. Across the Pond is a podcast about the most discussed and anticipated books on both sides of the Atlantic. Doireann was interviewed for their seventh episode, which was posted on June 1, 2021. You can listen to it here.

Pick up your copy of A Ghost in the Throat from Biblioasis!

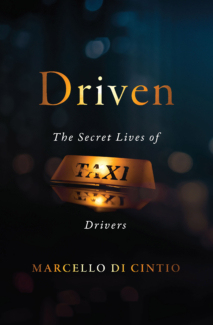

DRIVEN

Marcello Di Cintio, author of Driven The Secret Lives of Taxi Drivers (May 4, 2021), was interviewed by Piya Chattopadhyay on CBC’s The Sunday Magazine! The interview was aired on Sunday, May 16, 2021. You can listen to it here.

Marcello Di Cintio’s Driven The Secret Lives of Taxi Drivers received a starred review from Quill & Quire! The review was published online on May 20, 2021, and it was published in the print June 2021 issue. You can read it online here.

Reviewer Kevin Hardcastle raved,

“Di Cintio, a two-time winner of the W.O. Mitchell City of Calgary Book Prize, lets the drivers’ individual stories shine in these anthologized glimpses while reserving his own judgments … In a world of ride shares and COVID-19, the stories in Driven are coloured by the spectre that this livelihood could be lost … But there is hope in these stories and a powerful dose of humanity in how these drivers endure, all while looking squarely at inequities and uncertainty. The cabbies profiled by Di Cintio are not here just to tell stories; they reveal truth in a way that may well disarm and sharply adjust the perceptions of many readers.”

Marcello Di Cintio also published an article in the Globe & Mail titled “‘Road’ scholars: why every taxi driver possesses their own type of genius”! The article was published online on May 21, 2021, and it was published in the print issue of the Globe the following weekend. You can read it online here.

Finally, Marcello Di Cintio’s Driven The Secret Lives of Taxi Drivers received a great review in the Literary Review of Canada! The review was published online on May 26, 2021, and it will be in the June 2021 print issue of the LRC. You can read it online here.

Reviewer David Macfarlane wrote,

“No big event kicks Driven into gear. Nobody is a celebrity. There is no specific wrong to be righted, no particular injustice to be exposed. Indeed, Di Cintio consciously abjures the best-known tropes of cab driving … Instead, he sticks to wanting to know about cab drivers, and this impulse—plain, old-fashioned inquisitiveness—is a journalistic force not to be underestimated.”

Get your copy of Driven today from Biblioasis!

WHITE SHADOW

Roy Jacobsen’s White Shadow (April 6, 2021) was featured by the New York Times in their list “The Ultimate Summer Escape: Historical Fiction”! The list was published on May 27, 2021. You can read the article on their website here.

Roy Jacobsen’s White Shadow (April 6, 2021) was featured by the New York Times in their list “The Ultimate Summer Escape: Historical Fiction”! The list was published on May 27, 2021. You can read the article on their website here.

Reviewer Alida Becker wrote,

“The heroine of Roy Jacobsen’s White Shadow knows every inch of her home turf, a tiny island off the coast of northern Norway that her people have inhabited for generations … The novel’s account of Ingrid’s experience of World War II is unsettlingly easy to follow.”

On June 1, 2021, White Shadow was the featured novel at Interabang Books’ (Dallas, TX) June Book Club meeting. The book club was highlighted by PaperCity Magazine in their list “The Best Event Series to Catch for a Dallas Summer Well Spent”. The list was published on May 26, 2021, and you can read it on their website here.

Grab your copy of White Shadow from Biblioasis!

We’re excited to announce that Rinaldo Walcott’s On Property has been nominated for the 2021 Toronto Book Awards! The longlist was announced yesterday on June 29, 2021. Rinaldo Walcott is one of 10 authors on the longlist. The shortlist will be announced in August 2021.

We’re excited to announce that Rinaldo Walcott’s On Property has been nominated for the 2021 Toronto Book Awards! The longlist was announced yesterday on June 29, 2021. Rinaldo Walcott is one of 10 authors on the longlist. The shortlist will be announced in August 2021.