Want to get new excerpts, musings, and more from The Bibliophile right away? Sign up for our weekly newsletter here!

***

Editors’ note: While The Bibliophile was taking its summer nap, we were wide awake and thinking about some kinds of features we’d like to run in this space. Thus, this week’s installment is the first in a charmingly irregular series we should probably call “Why We Published It,” which debuts with Vanessa’s response to Anne Hawk’s The Pages of the Sea.

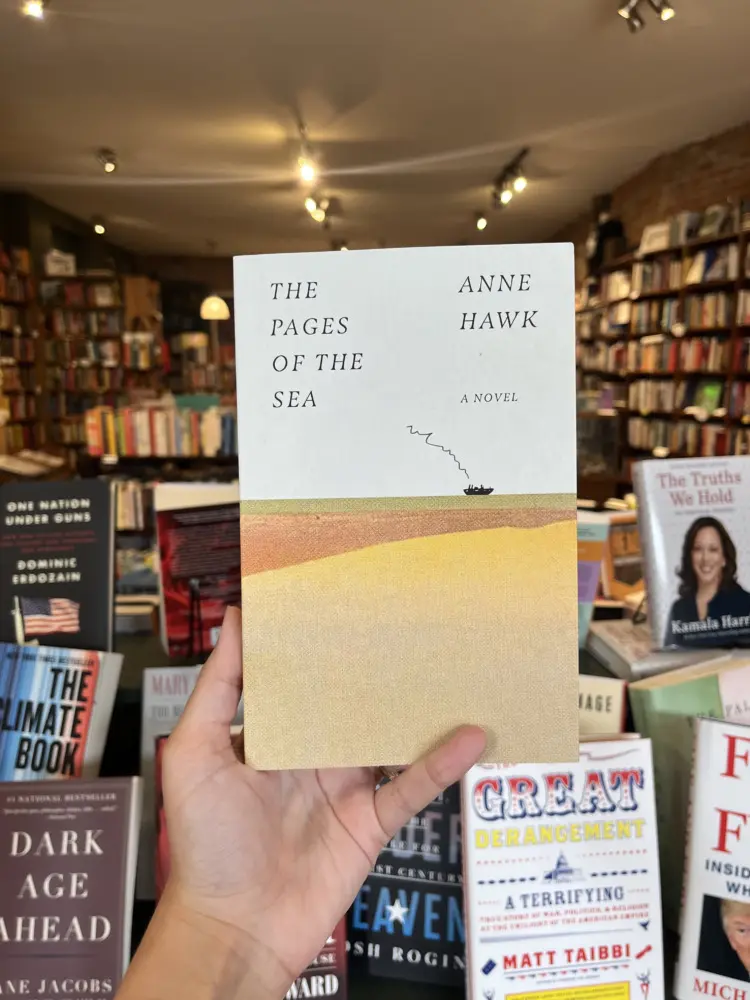

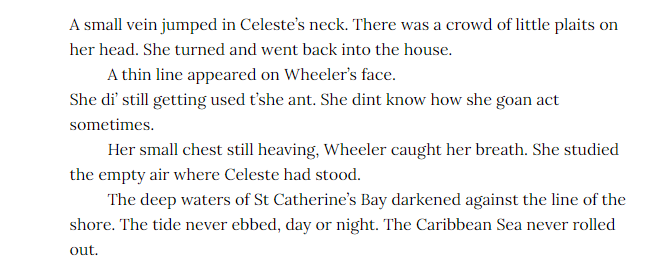

Photo: You can pre-order a copy of The Pages of the Sea today!

As a kid growing up in southeastern Pennsylvania in the 1980s, I spent a lot of time by myself. We lived on the rural outskirts of an already rural place, four miles from a town of fewer than 1,600. Between the turquoise waters of the public swimming pool—what was to me, at age six, the hallowed centre of the known universe—and the farmhouse I grew up in: cornfields and fields of tobacco and soy, rolling hills and the rocky glens and old-growth trees that stair-step the lower third of the the county down to the wide Susquehanna. A trip into town to the grocery store or drive-through at the bank was a source of excitement, and seeing my father’s brown Ford Ranger emerge from behind the woods at the top of the ridge that formed the southern edge of the little valley we lived in engendered a chanting sort of song that I’d sing as he made the left hand turn onto our little road, technically two lanes, but closer to one and a half, and into the long stone drive at the end of a day he’d spent pumping gas and changing tires at the gas station in town.

When I was eight or nine, my father got a new job, one that required he wake at 4:30 in the morning and drive an hour to a welding shop where, from what I could tell, he spent the day burning tiny holes in his t-shirts. Around this time, my mother stopped her part-time work cleaning houses and took a night shift stocking shelves at the grocery store. Now she slept all day, and left for her job as my father was coming home, exhausted, from his. What did I know, what did I know, as Robert Hayden asked, of the sacrifices they made, what it took from them to meet their responsibilities the best they could? Not much, if anything at all.

I did know there was a meadow with a modest herd of Holsteins and that sometimes there was a bull, and when that was the case I could not climb the metal gate or slip under the barbed wire to take the old dirt footpath along the dry creek to the tree with the bent trunk, the moss-covered one I liked to sit on. I knew I had to make myself lunch in the summer, and quietly, so as to not wake my mother, and when she was promoted, for her hard work, to a daytime position, I knew where we kept the key to the front door to let myself in after school. I can’t remember if I was told to lock it behind me: probably not. But other than these rules and similar, and school, and church most Sundays, I was left almost entirely to my own devices. I swung on the tire swing that hung from the weeping willow, and played in the sandbox, and practiced with my youth-sized recurve bow, shooting at a stack of haybales against the barn. I kicked a soccer ball against a wall and practiced free throws in the driveway and shot my BB gun at the stop sign on top of the hill, straining to hear the faint ping. I walked the fencerows back towards the deeper woods as far as I was not afraid to go, and I read stacks and stacks and stacks of books.

***

Books: have we come round, at last, to the point? The Pages of the Sea, a debut novel by Anne Hawk, landed in my inbox one day in April courtesy of Dan, who’d received it from the good people at Weatherglass Books, an independent press in the UK. I took a galley home and started reading that night. (Some childhood habits, happily, never change.) In the opening scene, Wheeler, the novel’s young protagonist, is sitting outside watching her aunt, Celeste, go in and out of the house:

We quickly learn that Wheeler and her two sisters have recently moved into the house they now share with their two aunts and three cousins because their mother has gone overseas to work in England, and “[e]ach month a postal order arrived from England covering the sisters’ room and board.”

When Tant’Celeste speaks to Wheeler, it’s to ask a question she can’t answer: where the rest of the children have gone. When Wheeler doesn’t respond, Celeste sends her to look for them, and when she returns alone, she’s not sure what to make of her aunt’s response:

It’s a beautiful piece of exposition, these opening four pages: Hawk immerses us in Wheeler’s world, capturing the child’s discomfort in the unfamiliar situation and her uncertainty about the mysterious actions and emotions of adults, and establishing both conflict and setting, one inextricable from the other. Wheeler’s interior monologue, written in the rich cadences of her native Caribbean English, with dialogue rendered in the same, voice the lived experience of a time and place and together join a standard English narration in what Hawk describes as a collaboration between Englishes that complement and often overlap each other. It’s a technique that puts me in mind of Their Eyes Were Watching God, Zora Neale Hurston’s brilliant vernacular novel of the American South, which starts gazing out towards a metaphorical sea and then introduces a young protagonist growing up without a father or mother, and of another of our favourite Biblioasis books: Roy Jacobsen’s The Unseen, with its inventive English translation, by Don Bartlett and Don Shaw, of an untranslatable Norwegian dialect—and another novel that begins with a small girl living on a small island, wondering about the world of adults. Like both of those books—one a classic of Modern literature, one an International Booker finalist and bestselling Biblioasis novel—this one welcomes its readers into its world on its own terms from a position of imaginative generosity and of love. It’s often said a great book teaches you how to read it: let me be one of the first, and certainly not the last, to say this is a great book.

For reasons likely obvious by now, my response was: sign it up. And so I couldn’t be more pleased to be writing this to you, Dear Reader, the week before the Canadian publication of Anne Hawk’s brilliant debut novel, The Pages of the Sea. I hope it will find you, wherever you are and wherever you are from, and it will remind you what literature is for. And I hope you’ll stay tuned for September 27, when The Bibliophile will feature an original essay by Anne Hawk on Caribbean English.

BC readers: Upstart & Crow will host the launch of The Pages of the Sea on October 3, 2024 at 7:00PM.

Vanessa Stauffer

Managing Editor

***

Keep up with us!

We’re thrilled to share that this week, The Pages of the Sea by Anne Hawk was announced as making the fiction category shortlist for the 2025 OCM Bocas Prize for Caribbean Literature! The announcement was made on Sunday, March 16, and can be read in full here.

We’re thrilled to share that this week, The Pages of the Sea by Anne Hawk was announced as making the fiction category shortlist for the 2025 OCM Bocas Prize for Caribbean Literature! The announcement was made on Sunday, March 16, and can be read in full here.