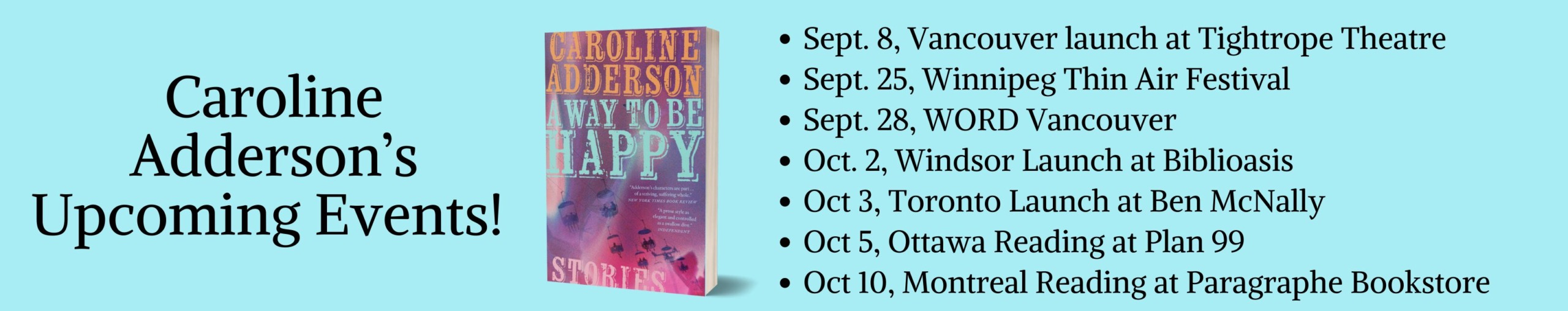

The Bibliophile: Biblioasis Women in Translation

Want to get new excerpts, musings, and more from The Bibliophile right away? Sign up for our weekly online newsletter here!

***

Some of us are still enjoying sun and sand, but we’re bringing the Bibliophile back with a feature for Women in Translation Month, highlighting not only some of our fabulous writers, but the amazing work done by their dedicated translators.

We’ve got novels, nonfiction, and linked stories—including one book forthcoming next year! Check them out below, and join us in celebrating translated works by commenting some of your favourite translations by women (from Biblioasis, or elsewhere).

Ashley Van Elswyk

Editorial Assistant

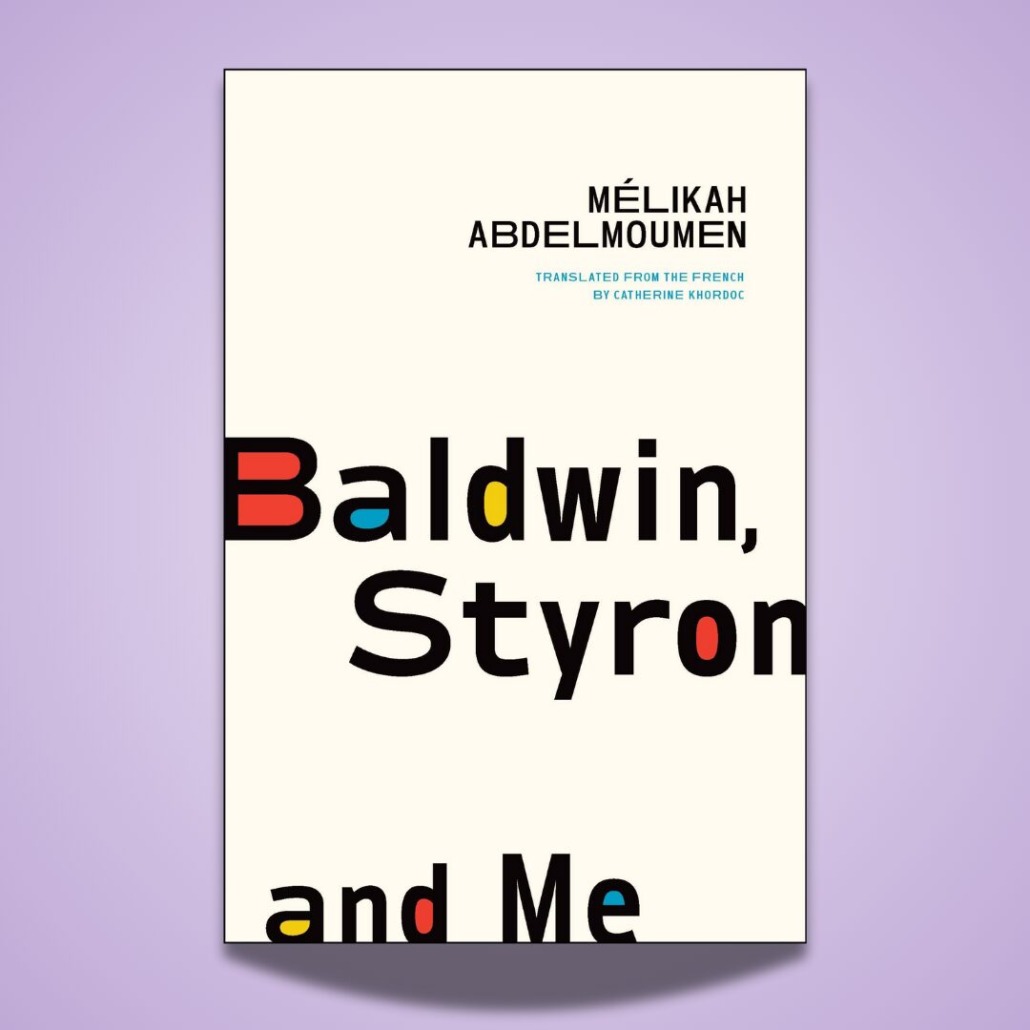

Baldwin, Styron, and Me

Mélikah Abdelmoumen, translated by Catherine Khordoc

An unlikely literary friendship from the past sheds light on the radicalization of public debate around identity, race, and censorship.

In 1961, James Baldwin spent several months in William Styron’s guest house. The two wrote during the day, then spent evenings confiding in each other and talking about race in America. During one of those conversations, Baldwin is said to have convinced his friend to write, in first person, the story of the 1831 slave rebellion led by Nat Turner. The Confessions of Nat Turner was published to critical acclaim, winning the Pulitzer Prize in 1968, and also creating outrage in part of the African American community.

Decades later, the controversy around cultural appropriation, identity, and the rights and responsibilities of the writer still resonates. In Baldwin, Styron, and Me, Mélikah Abdelmoumen considers the writers’ surprising yet vital friendship from her standpoint as a racialized woman torn by the often unidimensional versions of her identity put forth by today’s politics and media. Considering questions of identity, race, equity, and the often contentious public debates about these topics, Abdelmoumen works to create a space where the answers are found by first learning how to listen—even in disagreement.

Near Distance

Hanna Stoltenberg, translated by Wendy H. Gabrielsen

“Stoltenberg’s elegant prose makes each scene . . . so engaging that it gives plot a bad name.”—John Self, Guardian

For her entire life, Karin has fled anything and anyone that tries to possess her. Her job demands little, she mostly socializes with men she meets online, and she’s rarely in touch with Helene, her adult daughter. But when Helene’s marriage is threatened, she turns, uncharacteristically, to her mother for commiseration, and a long weekend away in London. As the two women embark on their uneasy companionship, Karin’s past, and the origins of her studied detachments, are cast in a new light, and she can no longer ignore their effects—on not only herself and her own relationships, but on her daughter’s as well.

An unnerving, closely observed study of character—and the choices we do and do not make—Near Distance introduces Hanna Stoltenberg as a writer of piercing insight and startling lucidity.

Love Novel

Ivana Sajko, translated by Mima Simić

Winner of the HKW Internationaler Literaturpreis • Shortlisted for the 2023 Dublin Literary Award

Love in late capitalism: in an unnamed city, a husband and wife wage a silent war of rage and resentment. He, an out-of-work Dante scholar, is trying to change the world—and write a novel. She was once a passable actress, but now she’s failing at breastfeeding. They take on gigs and debts. He drinks cheap wine; she cleans obsessively. In their two-room flat the tension rises and turns exquisite: the rent is past due, their careers have stalled, the regime is crumbling, and there’s always the baby, the baby who won’t stop crying.

Intense and astutely ironic, devastating and darkly comic, Ivana Sajko’s Love Novel takes a scalpel to the heart of modern married life.

And forthcoming…

Keep an eye out in January for Ivana Sajko’s next book, translated again by Mima Simić!

Every Time We Say Goodbye is a novel about departures, about childhood, about the end of love and about the lost idea of escaping to a better place. Each chapter is one long sentence that moves from the past to the present, from the skin of a frightened boy to the suit of an adult man, from one end of Europe to the other, following the fate of a man who travels from a coastal town on the Adriatic to Berlin in order to start again. Ivana Sajko paints a portrait of an intellectual at a crossroads with stylistic care and precision.

The Future

Catherine Leroux, translated by Susan Ouriou

Winner of Canada Reads 2024 • Longlisted for the 2025 Dublin Literary Award • Longlisted for the 2024 Carol Shields Prize for Fiction

In an alternate history of Detroit, the Motor City was never surrendered to the US. Its residents deal with pollution, poverty, and the legacy of racism—and strange and magical things are happening: children rule over their own kingdom in the trees and burned houses regenerate themselves. When Gloria arrives looking for answers and her missing granddaughters, at first she finds only a hungry mouse in the derelict home where her daughter was murdered. But the neighbours take pity on her and she turns to their resilience and impressive gardens for sustenance.

When a strange intuition sends Gloria into the woods of Parc Rouge, where the city’s orphaned and abandoned children are rumored to have created their own society, she can’t imagine the strength she will find. A richly imagined story of community and a plea for persistence in the face of our uncertain future, The Future is a lyrical testament to the power we hold to protect the people and places we love—together.

The Music Game

Stéfanie Clermont, translated by JC Sutcliffe

Winner of the 2023 French-American Translation Prize for Fiction

Friends since grade school, Céline, Julie, and Sabrina come of age at the start of a new millennium, supporting each other and drifting apart as their lives pull them in different directions. But when their friend dies by suicide in the abandoned city lot where they once gathered, they must carry on in the world that left him behind—one they once dreamed they would change for the better. From the grind of Montreal service jobs, to isolated French Ontario countryside childhoods, to the tenuous cooperation of Bay Area punk squats, the three young women navigate everyday losses and fears against the backdrop of a tumultuous twenty-first century. An ode to friendship and the ties that bind us together, Stéfanie Clermont’s award-winning The Music Game confronts the violence of the modern world and pays homage to those who work in the hope and faith that it can still be made a better place.

In good publicity news:

- The Future by Catherine Leroux (trans. Susan Ouriou) and Baldwin, Styron, and Me by Mélikah Abdelmoumen (trans. Catherine Khordoc) were both included in Read Quebec’s feature for Women in Translation Month.

- Let Me Go Mad in My Own Way by Elaine Feeney was reviewed in Publishers Weekly: “With arresting imagery and skillful shifts in perspective, Feeney weaves together these narrative threads to gut-wrenching effect . . . It’s a potent drama of a family shaped by a nation in upheaval.”

- Dark Like Under by Alice Chadwick was reviewed in the Winnipeg Free Press: “A wholly engrossing, multi-layered story told with a slow burn.”

- On Oil by Don Gillmor was reviewed in the Literary Review of Canada: “Gillmor exposes the many myths of a multi-billion-dollar industry . . . [A] strong indictment of the most earth-destroying economic force that exists today.”

- Casey Plett, author of On Community, was interviewed on the TELUS Talks podcast.

- On Book Banning by Ira Wells was reviewed in the Seaboard Review of Books: “A thought-provoking read . . . For readers concerned about intellectual freedom, On Book Banning is worth a look.”