The Bibliophile: Ripper: The Making of Pierre Poilievre

Want to get new excerpts, musings, and more from The Bibliophile right away? Sign up for our weekly online newsletter here!

***

Late one evening in 2023 I received a Facebook message from a pair of high school friends I hadn’t seen since graduation more than thirty years before. They were heading down from Chatham on a day-long cruise on their Harleys and were going to stop by the bookstore, and they were wondering if I’d be around. I made sure I was, and when they arrived, we went to the Walkerville Brewery to catch up. It was a wonderful couple of hours: both these men, despite our losing contact for decades, were fellows I had wondered about from time to time, good men who, when boys, helped bring me through very rough patches. I even lived with one for a while when my own home life was fraught. When they left that aft, we promised to keep in touch, and later that eve came an invitation to a WhatsApp group called, simply, The Boys. My two friends were connected to half a dozen others from high school, and they used the group to keep in touch, pass jokes and memes, and arrange meeting times at the local bar. Most of it was typical middle-aged silly fun. I didn’t participate much, but I got a kick out of the back and forth, sharing a bit of these guys’ lives.

But there was one thing that surprised me. With increasing regularity, various members of this group shared political posts, almost all of them focusing on Prime Minister Trudeau’s latest gaffe or supposed idiocy; others attacked Liberal policies on the pandemic response, the housing crisis, and the carbon tax. More than once, I was tipped off to some new “scandal” via these messages before some variant of the same story turned up in the pages of the Globe and Mail or the National Post. The messages were deeply partisan, and most (but not all) couldn’t have withstood much more than a quick Google, let alone a proper fact-check. But that didn’t matter, because there was no fact-checking. Several times I almost said something, then thought better of it: I did not want to get into a political debate, nor did I feel it was my place. I stopped engaging much and just watched, growing more and more fascinated and concerned.

Occasionally, someone would share a political story that wasn’t Canadian at all. After the last Russian election, a member of the Boys shared an interview between a Russian-supported online news agency and a Russian propagandist explaining that Putin had actually earned his resounding election victory as a result of the genuine love and faith entrusted to him by Russian voters, and that Russia had a stronger democracy than either Canada or the US. One of the boys responded with something akin to “When Putin defeats Ukraine I hope his next stop is Canada, where he can help finally rid us of Trudeau.”

These were not boys, or men, I would have ever expected to be overtly politically engaged. Our parents tended to think about politics dutifully and when they needed to: it wasn’t a topic of casual interaction. And we certainly weren’t political as kids, more interested in the latest hardcore sound (my ears still ring from 1988’s Anthrax concert), or scoring a mickey of something to drink in the park on Friday night. As men, they all work hard, demanding jobs; they have children and wives and mortgages; they look forward to Friday night at Chuck’s, a few pops and more laughs—who couldn’t use more of both? But here they were, passing along slickly made political memes and videos with increasing regularity, whether they were of Conservative or Russian origin, bashing the government and championing the person that everyone said would be the next prime minister of Canada: Pierre Poilievre. For the Boys, this couldn’t happen fast enough.

*

Photo: Mark Bourrie reading from Crosses in the Sky at the Biblioasis Spring Launch at Biblioasis Bookshop, May 2024.

Towards the end of last May, Biblioasis hosted a book launch in Windsor. Mark Bourrie, whose Crosses in the Sky we had just published, was among the authors, and the next morning he and I met for coffee. Conversation naturally turned to his next project. Mark wanted to gather, revise, and expand some of the work he’d previously published on Great Lakes shipwrecks; he had an idea for a book on African exploration and another on a strange American assassin: they were all of interest.

Mark had also previously pitched me several times on a Field Note about the crisis facing Canadian media, and the conversation switched to this. I told him about my Boys WhatsApp group, and how I feared that the app was being used to misinform and radicalize the men and others like them, and that no one seemed to be talking about it. But Mark reminded me that he had explored exactly this in books like Kill the Messengers and The Killing Game. And then he told me how the Conservatives had developed massive alternative media networks to amplify their message, allowing them to directly reach voters outside of traditional channels: what I had come across was just one small part of it. Pierre Poilievre, Mark argued, had mastered the use of social media to reach people through YouTube, where he’d posted thousands of videos over his career, and through other social media channels: his videos and messages were full of misinformation that he was rarely called on, but that were viewed between tens and hundreds of thousands of times. Poilievre had had the benefit of almost everything Canada offered, and yet he’d long been the angriest man on the political stage, constantly flinging rage. Mark said that he was terrified about what a Poilievre government might mean for the country: he feared that it would result in the cementing of a Trump-like political culture in Canada, and that many of the most vulnerable, including a lot of people who, as has been the case with Trump, would likely vote for Poilievre would suffer enormously. Poilievre was a partisan who had not substantially altered his political views since, as a teenager, he’d been exposed to the work of Ayn Rand and Milton Friedman. He was Canada’s great divider, and we needed to show people, before the next election, what he really stood for.

It was probably around this point that I suggested that, rather than writing a Field Note on the decline of Canadian media, Mark write one on Pierre Poilievre. I imagined something short and quick and polemical. We tossed the idea around for a while before he left. A few days later I received a short email, saying that he’d do it. We set the publication date for late Spring, to give ourselves a few months before the anticipated Fall 2025 election.

Photo: Three books from our Field Notes series: On Class by Deborah Dundas, On Property by Rinaldo Walcott, and the latest addition, On Book Banning by Ira Wells.

But what started as a Field Note morphed quickly into a full-length political biography. First pages arrived in December: we were at the early stages of editorial when Chrystia Freeland resigned as finance minister and the crisis seemed ready to topple the government and trigger an early election. I consoled myself with the idea that, rather than having the first critical biography of Poilievre—Andrew Lawton’s, from last year, at times seems to border on hagiography—we’d have the first critical biography of the new prime minister of Canada. Mark worked out when he thought the election would be called and asked what we would need to do to get the book done before that became the case. I told him, and he said that he could do it.

So we worked incessantly for the better part of two months, through December and the Christmas break, January and into the first week of February, writing, editing, rewriting. It was an immense, almost impossible amount of work, with the resulting manuscript expanding to flesh out its portrait not only of Poilievre, but of the Canada that has brought him to the brink of power. The thesis of this book is that Poilievre has always been what he is: a rigid partisan and attack dog and divider, or in the parlance of David Brooks, who, in a pandemic-era New York Times column on the political forces shaping the modern world, helped to give this book its title: a ripper.

Here’s the working cover copy:

As Canada heads towards a pivotal election, bestselling author Mark Bourrie charts the rise of Opposition leader Pierre Poilievre and considers the history and potential cost of the politics of division.

Six weeks into the Covid pandemic, New York Times columnist David Brooks identified two types of Western politicians: rippers and weavers. Rippers, whether on the right or the left, see politics as war. They don’t care about the destruction that’s caused as they fight for power. Weavers are their opposite: people who try to fix things, who want to bring people together and try to build consensus. At the beginning of the pandemic, weavers seemed to be winning. Five years later, as Canada heads towards a pivotal election, that’s no longer the case. Across the border, a ripper is remaking the American government. And for the first time in its history, Canada has its own ripper poised to assume power.

Pierre Poilievre has enjoyed most of the advantages of the mainstream Canadian middle class. Yet he’s long been the angriest man on the political stage. In Ripper: The Making of Pierre Poilievre, bestselling author Mark Bourrie, winner of the Charles Taylor Prize, charts Poilievre’s rise through the political system, from teenage volunteer to outspoken Opposition leader known for cutting soundbites and theatrics. Bourrie shows how we arrived at this divisive moment in our history, one in which rippers are poised to capitalize on conflict. He shows how Poilievre and this new style of politics have gained so much ground—and warns of what it will cost us if they succeed.

Books should start hitting shelves at the end of March.

*

As we watch what Trump and Musk are doing in the US, and the license the last few weeks have given Poilievre and his team to make similar statements about cutting government bureaucracy; gender essentialism; deporting migrants; and the problems with Canadian foreign aid, it’s become even more apparent that this is a pivotal national election. And that’s before even considering the question of who is the better leader to guide the country through Trump’s proposed economic sanctions and provide a real alternative to what we see happening in the United States. If Poilievre is a ripper, who will be our much needed weaver? Only time will tell.

I’m immensely proud of the work that Mark has put in to make this book happen, and of the intelligence, care, and compassion that is central to it. I think Ripper offers a harsh but fair portrait of a talented politician built for opposition, but one who would make, especially at this particular moment in our history, a terrible first minister. But it’s an equally harsh portrait of who we as a people have increasingly become. Working on it has been a privilege that’s given me much pause; I hope it does the same for each and every one of you.

Dan Wells,

Publisher

***

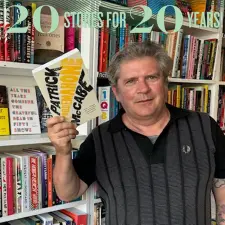

20 Bookstores for 20 Years: The City & The City Books

The City & The City Books in Hamilton, Ontario, is an energetic and highly curated store that offers an impressive collection of independently published titles from across North America and beyond. Owners Tim and Janet cultivate a welcoming atmosphere where you’ll feel at home coming in out of the cold to hunt down a hidden gem and enjoy lively conversations about your latest read (Check out their book club that meets every other month at the Hearty Hooligan!) Read on for why Dan sees The City & The City Books as a home away from home, and why owner Tim loves Patrick McCabe’s Poguemahone.

Dan on The City & The City Books: I first met Tim and Janet nearly two decades ago at a mutual friend’s book launch, the evening spent in ever-tightening circles talking about books and music. Almost immediately I felt a sense of kinship, so it wasn’t much of a surprise when I learned that they had left Big Smoke with the idea of opening an independent bookstore in Hamilton, Ontario. Nor is it a surprise that their shop is as good as it is, offering exactly the right mix of the anticipated and unexpected, with a particularly strong selection of the best independently published titles from across North America, and even further afield. Hamilton is a city blessed with a handful of excellent bookshops—including Epic and King W—but I have a hard time not thinking of Tim and Janet’s The City & The City as my home away from home, no matter how infrequently I get to darken its doorstep.

Why Tim loved the “unhinged spirit” of Poguemahone: “A rollicking 600 pages of Patrick McCabe’s—greatest talker since Francis Brady in The Butcher Boy. A free verse epic to be sang, yelled and danced. A book that forces you up out of the reading chair; to stomp around and read to the rafters.”

***

In good publicity news:

- Heaven and Hell by Jón Kalman Stefánsson (trans. Philip Roughton) was reviewed in the New York Times: “The good news is that Heaven and Hell is the first book in a trilogy, and there is more of this beguiling life to come.”

- The Passenger Seat by Vijay Khurana was named an March 2025 Indie Next Pick, and reviewed in the Literary Review of Canada: “The Passenger Seat will both mesmerize and refuse comforting resolution.”

- The Pages of the Sea by Anne Hawk was included in the CBC Books list “25 Canadian books to read during Black History Month 2025 and beyond.”

- Hello, Horse by Richard Kelly Kemick was reviewed in the Literary Review of Canada: “Kemick’s unique voice shines . . . By using dark humour to sharpen the impact of otherwise grim scenarios, he traverses the extremes of slapstick comedy and gory tragedy.”

- Near Distance by Hanna Stoltenberg (trans. Wendy H. Gabrielsen) was reviewed in the Winnipeg Free Press (“sparse, direct and discomforting prose”) and The Complete Review (“offers a strong character- and relationship-portrait”).