The Bibliophile: Gone a wee bit mad

Want to get new excerpts, musings, and more from The Bibliophile right away? Sign up for our weekly online newsletter here!

***

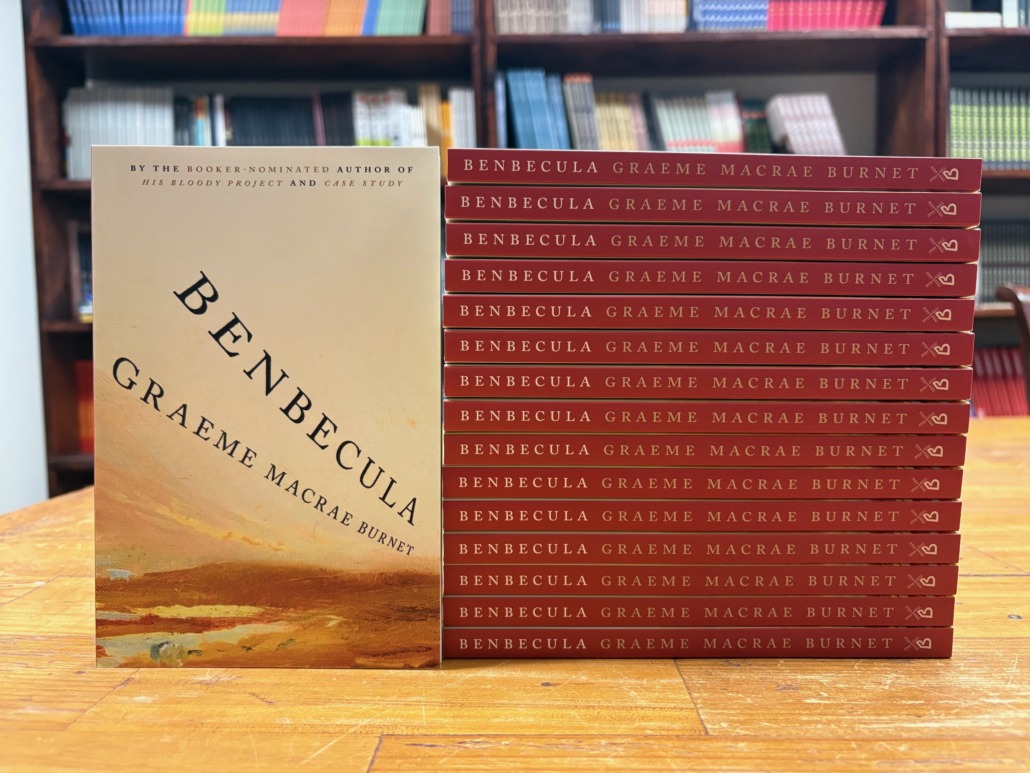

It’s a striking little book. Benbecula by Graeme Macrae Burnet. By striking I mean it is both very beautiful and violent and grotesque. It’s also funnier than you’d expect. Benbecula comes out in North America next week and it may be the book I’m most excited about. A story of madness and uncertainty told with a Samuel Beckett-esque voice, the novel is based on a true, little-known triple murder that took place on a remote Scottish island in the 1850s. It’s written from the perspective of the murderer’s brother, who describes what led to his brother’s actions, and as he tells us what’s happened, we start to question whether his brother was the only insane one.

Burnet first learned of the case when he was doing research for his internationally celebrated and Booker-shortlisted novel His Bloody Project. In some ways Benbecula is the inverse of that book—where His Bloody Project was about a fictional murder presented as fact, Benbecula takes a real murder and builds a fiction around it. And like all of Burnet’s work, it keeps you guessing on what’s true and what’s not.

Benbecula was the first of Burnet’s books that I’ve read, but after doing so I quickly sought out his others. And I know this post is to let you know about Benbecula in the hope that you will read it, but I would also like to shout out his 2022 novel Case Study, because I recently read it and can’t stop thinking about it. Just as I can’t stop thinking about Benbecula. This is fiction that genuinely makes me giddy to read. I don’t know if it’s the existentialist bent to his work that appeals to me as someone who read too much Beckett and Camus in university, or his dark humour, or the vividness of his language. It’s probably all of that, but I’ll stop gushing now.

For every book we publish, we put together a press kit for the media that we send along with advance copies of the book. Some of you are no doubt already familiar with this. The kit includes a description of the book, a biography of the author, and all the lovely things critics and booksellers have said about it. We also include a short interview with the author, usually conducted by me or Dominique, which we then like to post on Substack. I’ve been at Biblioasis exactly one year as of this past Tuesday, and doing these interviews is one of my favourite parts of the job. I really enjoyed my conversation with Burnet, and hope you do too.

Ahmed Abdalla,

Publicist

A Biblioasis Interview with Graeme Macrae Burnet

You’ve said that you first heard of the MacPhees’ story when you were writing His Bloody Project around twelve years ago. Why did you decide to return to it now? What about it made it stick in your mind all this time?

I was doing that research for His Bloody Project years ago and I came across the case of Angus MacPhee who killed three members of his family on this tiny Scottish island. It was of interest to me at the time because I was writing about a fictional nineteenth-century murder case in a Scottish Highland community, and here was one that actually happened, and that Angus was found to be criminally insane and so was not hanged was also interesting. At the time, it was tangential to what I was doing, but it stuck in my mind, not only because it was remarkable in itself, but because there was a French case, which actually inspired His Bloody Project, about a peasant called Pierre Riviere who killed three members of his own family. And Angus MacPhee killed three members of his own family. It just seemed so remarkable to come across cases that were so similar in some ways.

I returned to it because I was approached by a publisher here in Scotland who were doing a series of books based on real incidents in Scottish history and they asked me if I had any ideas. Once they said yes to this, I went back and really properly researched the case in the archives in Scotland and got down to the nitty gritty of it.

How extensive was that research?

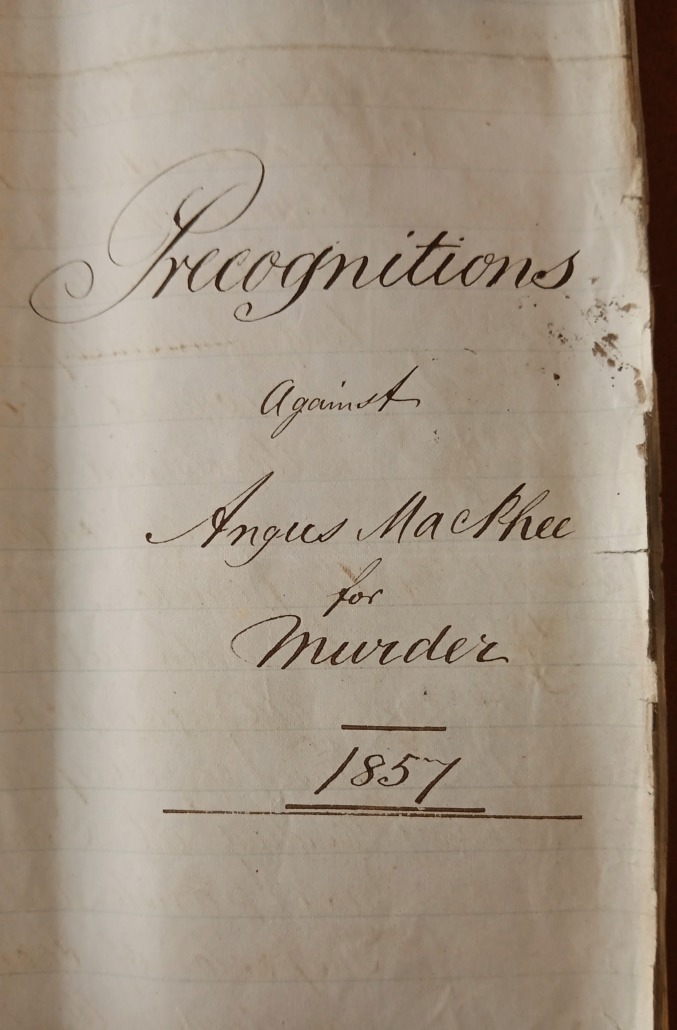

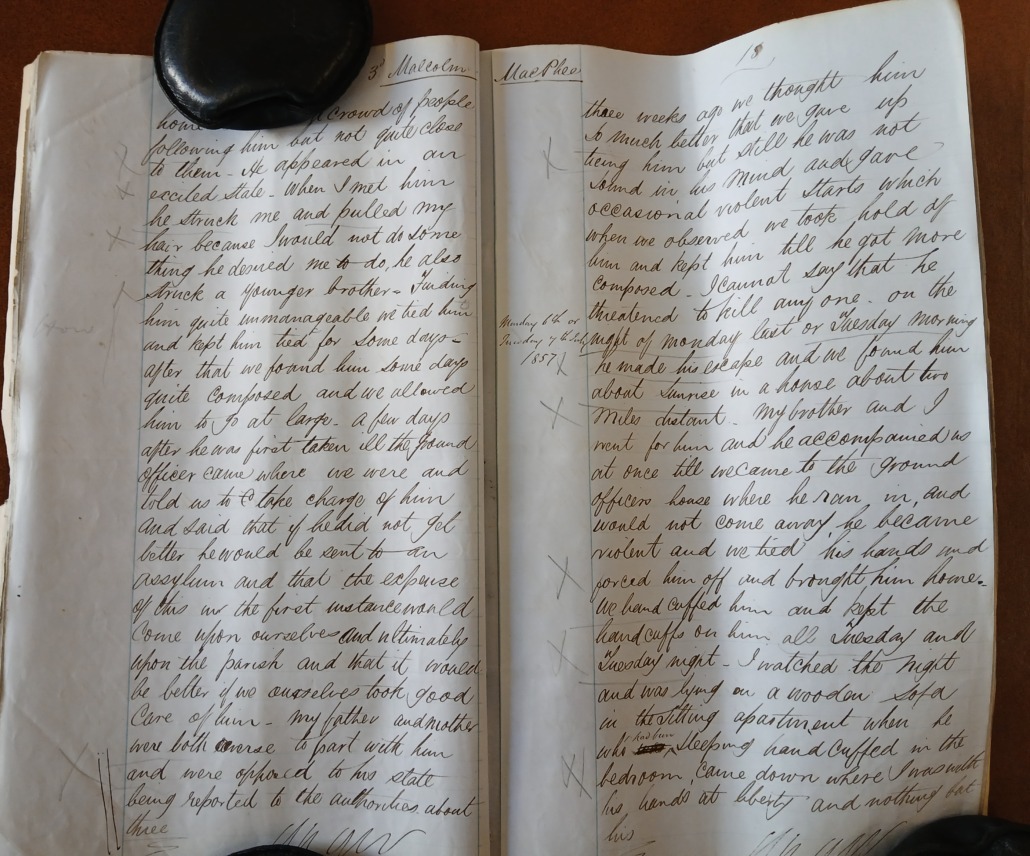

We have the National Records Office in Scotland, which contains all the documents relating to criminal cases going back to the 1800s. At that time, 1857, records of trials weren’t kept routinely, but what was in the archive were the “precognition statements.” These are basically witness statements that you would give to the police, and it’s what the witness would say at the trial. There were about 130 pages of those handwritten, completely original documents that I’m not sure anybody’s read before. I certainly haven’t seen references to them. Those 130 pages of precognition statements were the foundation of the book. Then there were also the legal documents, letters between lawyers and so on which were of less interest to me. It took me about a week or two to read through that material properly. It’s quite time consuming because it’s all handwritten. And I did other little bits of research into the historical side of what life was like in Benbecula at the time.

I think I heard you once say that you found archival material “evocating and inspiring.” What about it appeals to you and how does it inspire?

Partly it’s the physical documents. They come bundled up, tied with ribbon. Immediately you feel like you’re entering a secret world. And there’s the old vellum smell of the documents, and the handwriting, which changes depending on the author. They’re very evocative in that way. They almost transport you to the point when these documents were being created. It’s not like a print out of a Word document, which is just completely anonymous.

But it’s also the material that’s contained in these documents and the insight into the life of the characters that I was writing about. Little details like a young girl feeling that this character is following her along the path. Somehow you get surprising insights through reading these documents. I think any novelist would find that kind of material sort of inspiring and feel that it’s a starting point for a story.

And how much of it is real vs. fictional? It almost feels like true crime, assembling the basic plot from these real documents and the real case, but this is fiction which gives you the freedom to change the story.

That was the challenge for me because I was commissioned to write a fictional book and in some ways you could easily have written a nonfiction book about this case and the ramifications of the case. So very early in the writing, I decided to tell the story from the point of view of the murderer’s brother, Malcolm, and with that there’s two strands to the narrative. There’s the strand in which Malcolm describes the events leading up to his brother Angus’ murders and then there’s the strand in which Malcolm describes his current life in Benbecula. All the events in the past tense about Angus are based on the documents I read. All the present tense of Malcolm’s life is completely fictional. So it’s about 50/50.

Writing from Malcolm’s point of view was an interesting choice. To me, it gave the book a certain level of intimacy, a kind of disquieting intimacy as you realize he’s starting to go mad himself. And it also feels like a confession.

The decision to use Malcolm as the narrator was completely instinctive. The book had to be written quickly. I made that decision when I was in Kelvingrove Park in Glasgow. I sat there and wrote about five hundred words of what is now the opening. Of course as soon as you decide on your mode of narration, it imposes limitations on what you can write, but I stuck with it. Very quickly I realized that what I’m writing about is a man alone in an isolated cottage with his dark memories and he’s quite tormented in a disquieting way, as you would say.

Years ago when I was student, I was a massive aficionado of Samuel Beckett, particularly his trilogy of novels (Molloy, Malone Dies, and The Unnameable). I hadn’t read those books for thirty years, although they had a massive impact on me when I read them. I went back and listened to them as an audio book. There’s a brilliant reading by an actor called Sean Barrett which actually makes it more accessible because they’re quite avant-garde books. But I went back to Beckett because Beckett is writing about this increasingly disembodied voice, a person alone with his memories and you’re not sure what’s true and not true. I kind of drew on that Beckettian vibe.

I always found Beckett rather funny as well. I also think there’s a similar humour in Benbecula too.

I think it’s a very dark piece but the more times I went over it during the editorial process, weirdly I began to find it funnier and funnier, which probably says more about me than the book. A lot of it is quite grotesque, a really dark sort of humour. And it’s probably not very funny at all. I think I might have gone a wee bit mad writing the book.

Malcolm makes very rude remarks about his neighbors’ children or whatever, there’s a kind of humour there, but there’s also a sort of humour, and I don’t know if it’s even humour, but when something very violent or dramatic or unpleasant has happened, a paragraph will end with a nondescript observation or sentiment or an understatement. To me there’s a kind of humour in that which I think is quite Scottish.

You mentioned the Beckett influence, and it seems a lot of your work has a kind of existentialist bent to it. But were there any other influences on Benbecula?

Influence is a funny thing because you’re not always conscious of it. Somebody else might discern it or ascribe influence when you’ve never read that other text. But you’re right, I’m a dyed in the wool existentialist and I’m always concerned about questions of free will and agency and things like that. But I wasn’t thinking about that stuff when I was writing this book.

The only other thing I returned to mentally was Robert Louis Stevenson, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, which I also reread when writing the book. There’s a couple of quite meaty illusions to Jekyll and Hyde. The reason I went back to that text is because to me I was trying to create layers of textures in the book. As I was writing, I was thinking about the relationship between Malcolm and Angus. Angus is the “id” in Freudian terms. He’s unbridled, unfiltered, lust and instinct. He has drives and just follows them. Malcolm is the more sensible, normal brother. But it’s the relationship between the two which becomes closer. Malcolm becomes less “civilized” to use another Freudian term. (I’m not a Freudian by the way). But yes, there’s a bit of a Stevenson influence.

In the afterword, you talk about the “maniac” label and how, for some people, it’s used as a way of writing them off or dismissing an attempt to understand. Do you see Benbecula as a way of understanding that madness? By comparing Angus and Malcolm, the reader gets to see someone outwardly mad and one that’s more internal.

Malcolm’s mental universe does not really allow him to question or try things in the way that we do now in the twenty-first century. We have a different vocabulary and frameworks of thinking about madness. I don’t think Malcolm is trying to understand Angus. He almost just accepts what Angus did. But of course, it’s for the reader to speculate about why Angus may have committed the acts he did. Even in the afterword, I didn’t really want to get into too much speculation about why Angus did it because it would be no more than that, speculation. But also because I like the reader to do some work. I don’t want to say here is my interpretation of what happened 150 years ago, because people tend to see the author’s view as authoritative and that closes down the relationship with the material. And we still use words like maniac to divert ourselves from trying to understand why a person has committed an act of violence.

I really enjoyed the afterword. Part of me wasn’t sure if it was supposed to be nonfiction or fictional.

I’ve always wanted to write a nonfiction book and I love dealing with the research, so the afterword is nonfiction. But that’s interesting to me because when I wrote His Bloody Project, that was a fictional case written in a documentary style. So many readers thought it was based on a true case or that all the documents were real. Whereas Benbecula is the exact mirror image. It’s a real case written in a fictional style. All my work has some device in which I’m the translator not the author of the novel or something like that, so I’ll be very curious to know if readers are like “Yeah, right, he’s pulling our leg again.”

Was it more challenging to take a real case and write it into a novel or was it easier the other way around?

It was in a way more difficult because with the real life aspects of this book, I felt tied to the actual events. And so I’m describing certain things that actually happened or at least describing the version that I have access to, but of course I have to fictionalize them to the extent that I invent dialogue and conflate characters, but there’s a restriction in that. Whereas with the wholly fictional parts, I immediately felt much more free in the writing of it. We are inside Malcolm’s head and I wanted in a way to create the feeling that these thoughts are tumbling out of his head. The two parts were quite different to write simply because the Angus bits are really anchored in the facts of the case.

Did you actually travel to Benbecula as well as part of your research? What was that like?

Yeah, I went there in late January or early February and it was in the middle of a really bad storm. You have to take a ferry there. My first trip was canceled because the ferry didn’t run. Then I rebooked for the following week. The storm was coming but I knew I would get there, but I didn’t know if I would get off. So I spent a lot of the time there just looking at the travel app to see if the ferry was leaving. But it was really important for me to get there because in a sort of vaguely ethical way, I would have felt it was wrong to write about a place that I’d never set foot in. But also in terms of imagining the book, it was absolutely crucial that I went and stood where that house was and saw the landscape. I could now see the small universe of the book.

I also had a copy of this hand-drawn map of the murder scene that I got from the archive, which is all wet now. And the reason that it’s all wet is because I took it with me just before the storm. It was really windy and I was in this completely desolate stretch of land. It’s not beautiful at all. And I’m going around and there’s two settlements on this map and there were two sets of ruins on this piece of land. I also had another map from 1851, which we called ordinance survey maps, that marked all the settlements. So I could kind of match up the hand-drawn map with the other map. I can’t be 100 percent sure, but I feel quite confident I found the ruins of the house. I think that sort of thing is quite cool. But I don’t think it’ll start a birth of tourism for Benbecula.

Is there anything you want people to take away from reading this book?

I want them to feel immersed in the world of the book. I felt, and this is going back a bit to Beckett, that if you’re writing in a shorter form it offers the opportunity to be slightly more experimental. I just really wanted to get inside the head of this guy who lived in this landscape. So I would like people to feel immersed in this book, and they can make whatever they want of it, but I want them to feel it’s vivid and have a kind of visceral feeling on reading it.

Almost like they’re going mad themselves?

Hopefully.

In good publicity news:

- Benbecula by Graeme Macrae Burnet appeared on The Herald’s list of 10 books for November, and was reviewed in the Historical Novels Review:

- Let Me Go Mad in My Own Way by Elaine Feeney was included in the Washington Post’s list of 11 new paperbacks.

- Precarious by Marcello Di Cintio was reviewed in Publishers Weekly: “Thorough and damning . . . While offering precise and useful insights into the Canadian system, Di Cintio also provides rich food for thought about the role migration plays in the global order.”

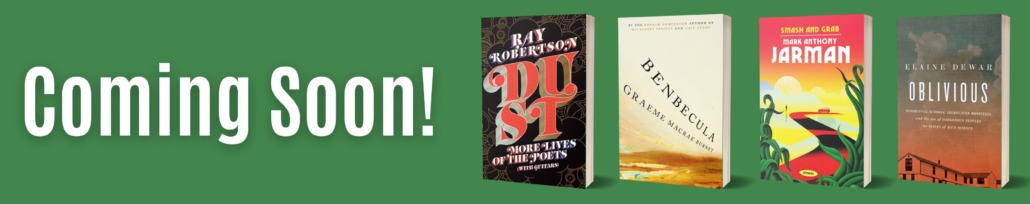

- A chapter from Dust: More Lives of the Poets (with Guitars) by Ray Robertson about Handsome Ned was excerpted in the Hamilton Review of Books.

- We’re Somewhere Else Now by Robyn Sarah was reviewed in the Montreal Review of Books: “We’re Somewhere Else Now marks a return to a voice both familiar and probing. [Sarah’s] poems carry an ease of camaraderie, a voice to commiserate with, lightly.”

- Vijay Khurana, author of The Passenger Seat, was interviewed on the Getting Lit with Linda podcast.

- UNMET by stephanie roberts was reviewed in Periodicities: “Crystalline and vibrant . . . UNMET, when finished, leaves the reader with more questions and thoughts, evaluating longings and appearances, pondering how to best meet the world with thoughtfulness and compassion.”

- The Mistress in Black (2025 Christmas Ghost Stories) was read on the Christmas Past podcast.