The Bibliophile: An Existential Tragedy

Want to get new excerpts, musings, and more from The Bibliophile right away? Sign up for our weekly online newsletter here!

***

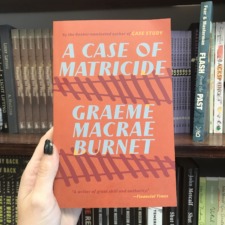

Graeme Macrae Burnet’s A Case of Matricide

Graeme Macrae Burnet first came across my radar when his second novel, His Bloody Project, made the Booker shortlist in 2016. Though I picked up a copy at the time, I never did get around to reading it: one of the unexpected consequences of jumping from the frying pan of bookselling to the fire of publishing is that my reading life has become constrained almost exclusively to books that we’re considering and/or publishing. So when, in late 2021, I learned that Graeme had a new book forthcoming, I asked Sara Hunt, the very fine publisher at Saraband in Scotland, if I could see a copy. Case Study left me feeling as if I were trapped in some kind of askew, Hitchcockian universe: when I started reading, I was certain that what had been sent to me was a novel; but by the time I’d read the preface and part of the first notebook I had put the manuscript aside and starting Googling to see if Collins Braithewaite was in fact a real person. My initial searches confused me further, as there seemed to be indications that he was a now forgotten acolyte of R. D. Laing; and even when I finally determined that Collins Braithewaite was a fictional creation, I couldn’t shake the sense that the boundary between what was real and what was imagined had been made more permeable than it had heretofore been. I loved the book, put in an offer with the agent, and luckily for all of us got it: by the time we published it in November 2022, it had already been nominated for the Booker Prize and voted an IndieNext selection by booksellers in the US; that year it saw rave reviews in the New York Times (where it made the Times 100 list), Wall Street Journal, New Yorker and elsewhere, and it continues, now two years later, to discover new readers every week.

As we were preparing to publish Case Study I allowed myself to go back and read Graeme’s other three books (for research!), including His Bloody Project and his two Gorski installments: each was animated by the same intelligence, social and psychological insight, subversion of expectation (more on which, anon), and playful reshaping of genre. All are crime novels of a kind: in GMB’s literary world, the usual boundaries between fiction and fact, high and low culture, genre and literary work, tend to become meaningless. He asks a lot of his readers, I think, because he respects them so much: and one of his asks is that they put aside their usual preconceptions about what is and what isn’t literature and worth reading.

Photo: Graeme Macrae Burnet at Mysterious Bookshop in 2022. Pictured with His Bloody Project, Case Study, and the first two Inspector Gorski novels: The Disappearance of Adèle Bedeau and The Accident on the A35.

A Case of Matricide is Graeme’s fifth novel and first since his Booker-nominated Case Study. Matricide is also the last novel in his trio of Simenon-inspired books exploring the life of the small-town provincial Inspector Georges Gorski. If in the first two novels, published by another press in North America, Gorski was a detective of promise and a certain acuity, he is in the current one increasingly a man undone: divorced from his high-class wife, living with his dementia-struck mother in a too-small apartment, and increasingly giving in to his thirst for an out-of-the-way bar’s dark corners. When a doppelganger of sorts shows up in his small town of Saint-Louis and begins tailing him, and then a long-time resident calls, convinced her son is about to murder her, and then an industrialist with likely criminal connections turns up dead of a suspected heart attack, Gorski tries to shake off his own entanglements and sense of complicity to pursue his hunch that these things are interconnected. But this attempt to reclaim agency proves impossible, resulting in an unexpected and tragic act, which forces Gorski to come to terms with the man he quite possibly has always been.

Though operating within the framework of a certain kind of genre novel, Burnet’s A Case of Matricide is much more of a literary existential tragedy. It’s as if Camus’s Meursault has been reborn as a late-20th-century provincial detective, undone by guilt and addiction. These Gorski police procedurals are used less to determine who-done-it and why, and more to explore questions of class, self-determination, and the ability of anyone to ever really escape their origins. Burnet also uses them to play a range of meta-fictional games in a way that will be familiar to readers of His Bloody Project and Case Study: for example, he purports to be not the book’s author but its translator (with the author listed as Raymond Brunet, an anagram of his own name); and that the books were written decades ago, only discovered after the suicide of the author, and only published after the author’s mother’s death (given the title of the novel, for quite obvious reasons). All of his previous books have been literary puzzles, and this one is no different: it took this reader weeks, over multiple readings, to untangle what was going on. Indeed, this process is still, nearly a year after first reading it, ongoing, and not just with me: I had a conversation last week with John Metcalf, one of the earliest readers of the book, where he started talking about it once again, explaining how Gorski’s story and what occurs within it continues to take on new shapes. When was the last time a crime novel, or any work of literature, did that for you?

In the final pages of Matricide, Burnet also subverts in a fashion I’ve never seen before the usual expectations of this kind of crime novel and how they are supposed to end, in a way that is both literarily and emotionally effective and much more reflective of the nature of power and the way that most of us, however we may view ourselves, tend to acquiesce to it. I don’t want to say any more than this, but I would love to know what readers think about this ending when they finish the final chapter.

GMB’s A Case of Matricide is certainly for lovers of intelligent crime fiction; but it will also appeal to those for whom crime fiction isn’t their usual bag. When Vanessa read Matricide, she mused aloud that perhaps she might really love crime fiction after all. I suspect that this isn’t the case: that what she loves is the work of Graeme Macrae Burnet. So do I; and so, if you give Matricide a chance (and though this isn’t the first Gorski book, and it may well be the last, I don’t think that they have to be read in order: and I’m not just saying that because the publisher of the first two books also publishes Melania Trump, Robert F Kennedy Jr, and Rand Paul!) may you.

To learn more, read this short interview conducted by Dominique Béchard with Graeme. And then go pick up a copy for your nearest independent. There are fewer better ways to spend a blustery November weekend.

Dan Wells,

Publisher

***

Photo: Graeme Macrae Burnet, sweeping the competition at shuffleboard in Chicago during his Fall 2022 North American tour.

An Interview with Graeme Macrae Burnet

A Case of Matricide is undeniably a crime novel, but it might not be classified as a crime novel by voracious readers of the genre. How would you respond to the division (which is at least present in the North American market) between genre fiction and literary fiction?

I agree that A Case of Matricide is a crime novel (or that it at least wears the garb of a crime novel), but it is perhaps not a conventional one. Throughout the writing of the three books of the Gorski trilogy, I’ve been conscious of the fact that I am writing within the crime genre, but that I perhaps subvert the conventions of the genre or to some extent play with the expectations of the readers, such as the resolution of the crime or mystery. Normally in a crime novel the detective figure (who is to some extent a surrogate for the reader) moves from a position of not-knowing to knowing, but in these books we don’t always know much more than we did at the beginning. I’m more interested in the detective figure—Georges Gorski in this case—investigating himself and coming to know something about himself that he was not aware of at the outset. There is also the meta-fictional side of the novels (I pose as the translator of a fictional French author’s work), which is perhaps somewhat unusual in the crime genre.

In terms of the division between genre fiction and literary fiction, as a writer perhaps with one foot in both camps, I make no distinction whatsoever in terms of my writing practice. I put every bit as much work into the Gorski novels as I do into my ostensibly literary novels (His Bloody Project and Case Study). The Gorski novels are not potboilers for me (actually in financial terms, they’re quite the opposite), but a literary project that I have spent about eight years writing. Here in the UK, there is certainly something of a distinction between crime and literary fiction in terms of literary kudos, but I think that’s eroded a bit in recent years, and I’ve been gratified with the seriousness with which critics over here have treated A Case of Matricide. I think in Europe, there has always been less of a division. Perhaps this is due to writers like Georges Simenon, Friedrich Dürrenmatt and Josef Škvorecký, who brought some serious literary chops to the crime genre. The French existentialists, and later some of the directors of the French nouvelle vague, were also very enamoured by the American hard-boiled fiction of Chandler, Hammett and the like, so I think the distinction has always been more porous there.

Though A Case of Matricide more obviously wears the cloak of crime fiction than some of your other work, playing with (and subverting) the usual expectations of the form, crime is still central to your more literary work as well. His Bloody Project is built around a historical crime; and Case Study is a crime novel of another kind, in which a young woman is convinced that a psychotherapist persuaded her sister to commit suicide. Indeed, in some ways your literary work deals with more sensational crimes than your crime fiction itself does. What is the role of crime in your literary world, and how and why do you handle it differently in your two writerly modes?

I agree with you about His Bloody Project, although if pressed I would call it ‘a novel about a crime’ rather than a crime novel, as I don’t think it shares the structure of more generic crime fiction. Having said that it is certainly the book of mine in which a violent crime has the greatest centrality. I struggle to see Case Study as a crime novel at all. I don’t think it has a crime novel structure and if a crime has been committed (and we never really know if that’s the case), I don’t think it has the same importance, as the novel develops, as the murders in His Bloody Project.

As to the second part of your question, regardless of what genre I may or may not be writing in, I don’t see myself as having different writerly modes. I approach the material in exactly the same way, which is that I try to inhabit the mind of the central character as much as possible—to see the world from their point of view. The crimes in my books are of importance primarily in the impact they have on the characters involved. A crime, by its nature, is a dramatic or violent event, so it’s likely to have the effect of throwing the world of the characters off-kilter, of placing them in unfamiliar or uncomfortable situations. So perhaps that is my attraction to crimes: that they force the characters into a position where they have to question or challenge themselves. In relation to A Case of Matricide, perhaps what is unusual is that Gorski—a cop—continually feels ill-at-ease and sometimes powerless. What interests me are his mental processes—his angst, if you like—as he goes about his investigative work, rather than the results themselves.

You’ve previously mentioned that you care most about character, that this is at the forefront when writing a book. Can you tell us more about how Gorski came to be, and perhaps why he’s progressed in some of the ways he has? (Without revealing too much, of course!)

Absolutely! For me, character is the most important aspect of any novel, whatever the genre. It’s the characters that draw us through the story, and in my books determine how the story unfolds. And no matter how clever or ingenious a book, I think it requires characters that elicit a reaction from readers (whether of empathy or loathing). Even after the details of the plot are forgotten, it’s the characters that remain in the minds of readers.

Georges Gorski first appeared as a secondary character in the first book of the trilogy, The Disappearance of Adèle Bedeau. He turns up at the apartment of the protagonist, Manfred Baumann, to question him about his connection to the disappearance of a local waitress. But I was intrigued by him and began to give him his own chapters. Then in the process of writing the book, he ended up sharing roughly equal billing with Manfred. By the time we reach A Case of Matricide he is absolutely the central character—aside from some interludes that provide a little breathing space between the main acts of the story, he’s in every scene.

I think of Gorski not as a cop, but as a man who happens to be a cop, and what I’m interested in exploring is not so much the unraveling of the events of the book, but the effect these events have on him as an individual. I’ve also, over the course of writing these books, become more and more fond of him. I feel his unease and am pained by his frequent humiliations and feelings of inadequacy. He’s not a detective in the tradition of Holmes or Poirot with their moments of insight and deduction. Nor is he in the tradition of the wise-cracking, alpha male who will beat a confession out of a suspect. He is a plodder, wedded to procedure. He has come to accept that he is something of a mediocrity, who has found his level as Chief of Police in a small town, where there is very little in the way of violent, dramatic crime.

Photo: A Case of Matricide by Graeme Macrae Burnet, third in the Inspector Gorski trilogy. Cover designed by Natalie Olsen.

Comparable to Raymond Brunet, the fictional author of this book, you’ve said that A Case of Matricide is the hardest book you’ve ever written. Why do you think that is?

I think A Case of Matricide was hard to write for two reasons. My two other novels, His Bloody Project and Case Study, were to some extent high concept books with a quite grand structural idea, and the feeling that there is a big idea behind a book helps you to keep going in the inevitable black periods of the writing process. In contrast, the Gorski novels—aside perhaps from the metafictional bracketing—are quieter books, more concerned with the minutiae of everyday interactions in an unremarkable town in France, so I was often haunted by the thought that no one would possibly be interested in a cop investigating something as trivial as the suspicious death of a lapdog or awkwardly flirting with the pretty florist in the shop below his apartment. But strangely enough, people do seem to be interested, and I must say that since A Case of Matricide has appeared here in the UK, I don’t think I have ever had such a positive and emotional response to a book.

The other reason the book was hard to write is that the book goes to some pretty dark places and of course, as the author, you must also go to these places, so it was quite emotionally draining.

You write about obsessive people: detectives, writers. I imagine that you see yourself as an obsessive writer (correct me if I’m wrong). How does it feel to conclude a lengthy project such as the trilogy? Is it freeing or difficult to no longer have to worry about Gorski?

I don’t particularly see myself as obsessive, or as an obsessive writer. Writing is a pretty grim process for me. I have to find ways to force myself to do it, but perhaps there is an element of obsession in the fact that I continue to do something I find so difficult.

It feels good to have completed such a big project. To me a trilogy is quite a special thing—as De La Soul said, Three is the magic number—and while A Case of Matricide can certainly be read in isolation from the other books, I wanted the three installments to kind of talk to each other and form a sort of organic whole. But while it feels good to have completed the project, I will miss mentally inhabiting the streets and bars of Saint-Louis (a real place of course). Despite the town’s ordinariness and the fact that I am continually rude about both it and its inhabitants, I’ve grown increasingly fond of it over the years.

What are you reading these days?

I devour everything written by Annie Ernaux, a writer whose hem I am not fit to touch. I also came across a book called Forbidden Notebook by Alba de Céspedes, written in the 1950s, but only just translated and published here by Pushkin Press (I love indie presses!). It tells the story of a housewife in postwar Rome and her relationships with her husband, boss and teenage children. It’s a novel of tremendous guile and subtlety—a masterpiece. Aside from that I read quite a lot of nonfiction, mostly recently on what was going on in central and eastern Europe during the Cold War, a period that fascinates me.

Who would you cast as Gorski if the book or trilogy were made into a film?

There’s a danger in this of putting a particular image of a character into readers’ heads, as I want everyone to be able to imagine Gorski as they see fit, but if you’re twisting my arm the Charles Aznavour of Tirez sur le pianiste.

***

In good publicity news:

- Comrade Papa by GauZ’ (trans. Frank Wynne) was reviewed in the Wall Street Journal: “GauZ’ avoids moralizing and is always alive to the humor and peculiarity of his stories.”

- Near Distance by Hanna Stoltenberg (trans. Wendy H. Gabrielsen) was reviewed in Kirkus Reviews: “Grimly fascinating . . . Page after page leaves the reader anxiously waiting for the other shoe to drop.”

- Heaven and Hell by Jón Kalman Stefánsson (trans. Philip Roughton) was given a starred review in Kirkus Reviews: “A moving story of loss and courage told in prose as crisp and clear as the Icelandic landscape where it takes place.”

- Roland Allen, author of The Notebook, appeared on several podcasts including Read to Lead, Something You Should Know, and Virtual Memories Show.

- Seth’s Christmas Ghost Stories were included in So Many Damn Books podcast’s Holiday Gift Guide 2024 episode, beginning at 26:30.

- A Way to Be Happy by Caroline Adderson was reviewed in FreeFall: “This clever and meticulously crafted collection from a writer who has mastered her art is a pleasure to read.”