Want to get new excerpts, musings, and more from The Bibliophile right away? Sign up for our weekly online newsletter here!

***

“I cannot praise a fugitive and cloister’d virtue, unexercis’d & unbreath’d, that never sallies out and sees her adversary, but slinks out of the race.”

—John Milton, Areopagitica

Over the past few weeks I’ve been on my phone reading the papers and various magazines and Substacks so much that my usage is up more than 177%. It’s difficult knowing how to act or be when faced with such a deluge of threats, which is probably the point of it all in the first place. In Windsor, 25% tariffs will quickly devastate both the wider community and my family, many of whom work in the auto industry; and with approximately 70% of the press’s distributed sales coming via the United States this year, the threat of tariffs leave us vulnerable. And these seem increasingly like lesser matters when compared to an American president who seems either incompetent, in the pocket of foreign or oligarchic interests, evil, or some combination of all three.

But, hey, at least we won the hockey game.

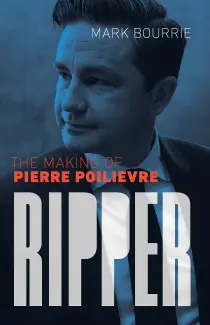

I have believed all my life in the power of books, if only because they have had so much power over me. Whether it be the work of a writer like Jón Kalman Stefánsson, who will remind me, almost as an aside, that “The ocean is cold blue and never still, a gigantic creature that breathes, most often tolerates us, but sometimes not, and then we drown; the history of humankind is not terribly complicated,” or that of a Jeannie Marshall or Mark Kingwell or Caroline Adderson, all of these and so many others (yes, including many we’ve not (yet) published) have taught me, repeatedly, to try to put aside my hubris and sense of certainty and to see the world anew. Each has, in recent years, in different ways, snapped the world for me into a slightly different focus. What more can we ask of our writers and their books? I have believed books can change the world, because they have so often changed mine. I’ve tried to keep that at the forefront in my work as a publisher, whether it be of fiction or, increasingly, of nonfiction. It was the animating impulse during the early days of the pandemic, and after the murder of George Floyd, for starting our Field Note pamphlet series. And it’s at the root of so much of the nonfiction we are publishing this year, from Mark Bourrie’s Ripper: The Making of Pierre Poilievre through to Marcello Di Cintio’s Precarious: The Lives of Migrant Workers, Don Gillmor’s On Oil, and Elaine Dewar’s Growing up Oblivious in Mississippi North. It’s our hope that these books will both inform and move the needle towards justice: however vague a concept this may be, most of us can at least agree on its general direction.

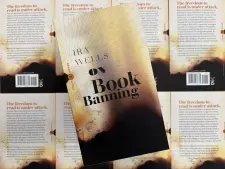

Photo: On Book Banning by Ira Wells. Cover designed by Ingrid Paulson.

In recent months, I have, at least at my worst moments, started doubting the ability of books to change much of anything. I remain convinced that books still have much to impart—as I said in my note last week, Mark Kingwell’s argument about conviction addiction explains for me better than anything I’ve read in newspapers and magazines and so very many Substacks what has led us to this particular historic moment—but I am deeply concerned that their reach, their public lives, have become dangerously shortened and constrained and I am not at all certain how to combat that. The reasons for this shortening are legion: disintermediation and its aftereffects, including political polarization, the dominance of foreign multinationals within the book industry itself, which greatly affects what readers have access to, and generalized exhaustion. It is perhaps also tied to the fact that the cold blue seems less and less tolerant, that for a variety of reasons one feels on the verge of drowning. It’s not, as with most things, that complicated.

Though I’ve also been struggling with a contradiction of sorts. Why is it, at the time that books have never seemed less central to people’s lives that the efforts to ban them have become increasingly common? On the left and on the right, in Canada and the US, book banners (however they may deny such a label) have made books and libraries, school and public, a central battleground to contest a range of social and political issues: religious and parental freedom, LGBTQ rights, issues of representation and inclusion and identity, access to diverse political arguments, and much else besides. And book banners on both the left and the right use many of the very same arguments to justify their exclusion of certain kinds of literature. It is all part of what Ira Wells, in his new Field Note On Book Banning (publishing next week in Canada, and in June in the US and abroad) calls the new censorship consensus. In attempting to ban access of certain populations to certain books, both sides are trying, to paraphrase Orwell, to control both the past, present, and future through a rewriting of all three, and each are convinced that they are on the right side of history (see above: Mark Kingwell and conviction addiction), though both are contributing equally to the undermining of democracy and our ability to think for ourselves. As Ira shows, there is nothing new in this, and if we examine the history of censorship (and the historical arguments against it) we will see why we can’t let the banners and censors win. And in that, too, perhaps be reminded of the conviction that makes what we do as publishers and readers and supporters of bookish culture so important in the first place.

Below, please find an interview that Ahmed Abdalla, publicist at Biblioasis, conducted with Ira about On Book Banning: Or, How the New Censorship Consensus Trivializes Art and Undermines Democracy.

Dan Wells,

Publisher

***

Photo: Ira Wells, courtesy of the author.

Can you tell me a little bit about yourself for readers approaching your work for the first time?

I am a professor of literature at Victoria College in the University of Toronto, a father of two school-aged kids, and a devoted, dyed-in-the-wool reader. I’m a book person.

What prompted you to write On Book Banning?

There were two moments. First, as I write in the book, my children’s elementary school undertook an equity-based “library audit,” during which our principal “joked” that she wished she could get rid of “all the old books.” Clearly, she was not alone in this thinking: the next fall, Peel District School Board, which consists of more than two hundred schools, undertook an equity-based book-weeding process in which some schools appear to have purged all books written before 2008.

Second, an episode I do not write about in the book, involves a talk on free speech that was delivered at the University of Toronto in 2023. The talk went off without a hitch—there was nothing even remotely controversial about the content or delivery—but I was struck, after the fact, to discover that our excellent students are deeply skeptical about the value of expressive freedom. Many students today believe that governments and other authorities should censor those harmful views; they do not understand why people with the “wrong” views should ever have a microphone or platform. My sense is that most young people today have never grappled with the foundational arguments (by John Milton, J.S. Mill, Frederick Douglass, and others) for free speech—arguments I wanted to outline clearly and succinctly, alongside the shocking and brutal history of censorship, which is the historical rule, not the exception. Of course, I was aware of the massive surge in censorship playing out in Florida and other jurisdictions across the United States—which may seem like a totally separate phenomenon, but which I argue is actually just another manifestation of the impulse to censor.

You start this book from the point of view of a parent whose children’s school was implementing a book-weeding process and give your first hand experience with it and the equity toolkit. How did this experience as a parent influence your thoughts on censorship and the structure of the book?

Yes, I joined a committee of parents who used the Toronto District School Board Equity Toolkit as part of this somewhat mysterious audit. (I say somewhat mysterious because the purpose of this exercise was never entirely clear to those who were involved—perhaps it was meant to educate us, the parents.) As someone who loves imaginative literature, and children’s literature, I was struck by the extent to which the toolkit manages to eliminate the imaginative and magical qualities of children’s lit. You get the sense that administrators want children’s lit to consist of little manifestos for the causes approved by the administrators. It’s basically a view of literature as propaganda. It’s alarming that those who are in charge of teaching the next generation of children how to read and think about books are doing so in these terms. I suspect that many children will turn off of reading entirely, which is of course already happening—they’re saddled with addictive technology that can make it hard to focus on anything for more than fifteen seconds. Childhood today sucks, and we’re making it worse.

What do you think the rise in book bans from both conservatives and progressives is saying about how we view literature? I know you also mention that part of the reason book banning thrives is when books and reading are devalued. Could you elaborate on that and why you think reading is being devalued?

I think that both conservatives and progressives see the library, and especially the school library, as a microcosm of society. They think—or rather believe, because all of this is playing out at the level of belief, rather than rational thought—that they can reshape society by transforming the library. They think of library books as levers they can pull to exert some kind of change in our culture. It doesn’t work that way, of course—John Milton argued more than four hundred years ago that “bad” ideas are perfectly capable of spreading without books—but this kind of library censorship does amount to a kind of symbolic violence, a way of signalling who does or doesn’t belong, a way of projecting social violence onto a scapegoat. At the same time, censorship thrives when books, and especially imaginative literature, are devalued. That is to say, when we reduce books to one putative “message,” that is a step in the direction of censorship, because it becomes easier to ban the books that convey the wrong messages. Once we accept that books and other art forms are delivery mechanisms for good or bad political content—and combine that assumption with the idea that we’re in a state of political emergency, that we’re facing existential stakes our very lives are on the line—then it can feel morally imperative to liquidate the “bad” messages, the bad books. Again, all of this is predicated on the idea that literature is reducible to messages (another mistake made by the toolkits), which they aren’t. The best novels are endlessly fascinating precisely because they are internally conflicted. They contain multiple voices and multiple messages.

What do you make of the idea that those who want to ban books never seem to refer to their actions as banning books/censorship? How does that inform their thinking?

According to the Ontario School Library Association, censorship “is the removal, suppression, or restricted circulation of literary, artistic, or educational images, ideas, and/or information because they are morally or otherwise objectionable. While the selector seeks reasons to include material in the collection, the censor seeks reasons to exclude material from the group.” That seems pretty clear to me. Whether you’re pulling Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye, Maia Kobabe’s Gender Queer, or William Golding’s Lord of the Flies—if you’re removing a book because it is “morally or otherwise objectionable,” that’s censorship, according to the OSLA. If you’re using an equity toolkit to “seek reasons to exclude material,” you’re practicing censorship. It’s all clear-cut. Of course, conservative and progressive book banners believe that censorship is something practiced by the other side. The conservatives believe that they are anti-pornography or anti-LGBTQ+ indoctrination; the progressives believe that they are anti-racist and anti-colonial. Both are convinced that they are right, and that their own righteousness legitimates, or even necessitates, their censorship. As I argue in On Book Banning, both groups are convinced they are saving children from harm. Instead, they are introducing new sources of harm.

In the book, you suggest we need to find a way to distinguish between purposefully offensive language and works that contain language that could offend but it makes sense historically or artistically that it is there. How should schools approach this?

I think it’s important to approach these questions with sensitivity, nuance, and an attention to historical context. I also believe that children, especially middle and high school students, are capable of understanding that social norms and language have changed over time. We do a disservice to students by whitewashing or sanitizing history. Students should be able to read Lawrence Hill. They should be able to read Toni Morrison. Teachers should be encouraged to teach these writers, not punished for doing so. Educators use the concept of “harm” in a very blunt way. It can refer to anything that might be legitimately traumatizing to something that might induce mild discomfort, if that. We shouldn’t treat students as fragile receptacles of information; instead, we should teach them that history, social norms, and language have evolved over time. Educators should be in the business of de-mythologizing, rather than re-mythologizing.

Censorship has never really gone away—it reflects a desire for social control, and each generation has to renew the fight for expressive freedom, which is the cornerstone of artistic expression and democracy.

You give a wide history of censorship in the book and it seems that arguments around censorship have hardly changed. Some people have always wanted to censor others because of language they deem offensive (with varying reasons as to why they find it offensive). What do you make of that? And did anything surprise you in your research?

Concepts like “obscenity,” “pornography,” and so on, are highly malleable. Less than a hundred years ago, James Joyce’s great novel Ulysses was banned as obscene; it’s hard to imagine anyone objecting to that book today. “Obscenity” is a living standard, which is to say that it shifts with the times. This cuts two ways. Yes, the zone of expressive freedom expanded in the postwar years, but there’s nothing permanent about those victories: censorship may be on the verge of a major comeback, especially with the revival of Comstock laws in the US. And of course, expressive freedom has never applied equally to all people. Some readers may be surprised to learn about the brutal persecution of LGBTQ+ publishers and booksellers which continued into the 1980s and 1990s. Censorship has never really gone away—it reflects a desire for social control, and each generation has to renew the fight for expressive freedom, which is the cornerstone of artistic expression and democracy.

Where do you think censorship will go from here? Do you think attitudes about book banning and the new censorship consensus will change? Either for better or for worse?

I wish I could say I thought things will get better. I do think that people are getting fed up with being told what they or their children are allowed to read. That said, the forces of censorship are ascendent in the US. The degree to which Trump will implement Project 2025 is an open question, but that document encourages the prosecution of teachers and librarians for dissemination of “pornography” as they define it. As the fall of Roe reveals, our legal victories are always tenuous. It can all be undone. In all likelihood, Trump will appoint two more Supreme Court justices. Historically, censorship and abortion have been linked—and it’s all possible that legal censorship is now on the cusp of a generational revival. I hope that On Book Banning may provide a useful reminder of the counterarguments, as well as the stakes. We’re going to have our work cut out for us. In the meantime, let’s leave the kids alone to read what they will.

***

- May Our Joy Endure by Kev Lambert (trans. Donald Winkler) was reviewed in the TLS: “This is a novel that makes readers take mordant notice of the world around them—but it is more than a mere succession of clever scores on self- aggrandizing elite progressivism.”

- Heaven and Hell by Jón Kalman Stefánsson (trans. Philip Roughton) was reviewed on WOSU’s The Longest Chapter: “Some novels are so extraordinary, it’s hard to do them justice in a review. This is one of them.”

- Roland Allen, author of The Notebook, was interviewed on The Art of Manliness podcast, about the history and power of the notebook.

- The Full-Moon Whaling Chronicles by Jason Guriel was reviewed in New Verse Review: “Guriel’s story, at its core, is not about the individual characters but about how an imagined book extends its imaginative influence into an imagined future world.”