The Bibliophile: Frontlist is Backlist

Want to get new excerpts, musings, and more from The Bibliophile right away? Sign up for our weekly newsletter here!

***

When frontlist is backlist . . .

Last week Dan outlined one of the eternal conflicts of independent publishing: the challenge of keeping books available for readers to discover, in an industry that is perpetually forward-focused, and within the pesky confines of time and space, i.e. in the face of return windows and the media’s own short attention spans, as well as the physical limitations of our vast yet rapidly overflowing warehouse shelves. (Speaking of the warehouse, our warehouse sale—200+ Biblioasis titles for five bucks a pop—continues through Labour Day.)

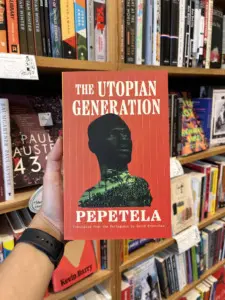

Given our ongoing obstinacy in the face of short (shelf and otherwise) lifespans, there’s a particular pleasure in saying that the most recent hot new Biblioasis release happens to be a book written thirty years ago: The Utopian Generation, by the great Angolan writer Pepetela. A Geração da Utopia was first published in its original Portuguese in 1992 by Dom Quixote. (And no, a windmill is never just a windmill.)

The Utopian Generation tells the story of four young revolutionaries and their fight for Angolan independence from Portugal. The four are living in Lisbon at the start of the War of Independence, and each must make choices that will have dire consequences for their futures. The novel follows them on their individual trajectories, from the optimism and passion inspired by the People’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA), to guerilla combat in Angola and the disillusionment of world-tested ideals and their gradual understanding of the self-renewing global hegemony of capitalism.

Richly detailed in its depictions of African and Portuguese culture, and peopled by vividly drawn characters whose lives reveal intricate insights into the racial and psychological tensions of colonialism, The Utopian Generation is widely considered in the Portuguese-speaking world the seminal novel of African decolonization, companion to novels like Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o’s Petals of Blood, Wole Soyinka’s The Interpreters, and Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Half of a Yellow Sun. You’ve certainly at least heard of these books, but without an English-language translation available, Pepetela’s novel has remained largely undiscovered outside of Lusophone cultures. We are terrifically excited that this edition, brought to us by longtime editor Stephen Henighan, and masterfully translated by the great David Brookshaw, is poised to change that fact.

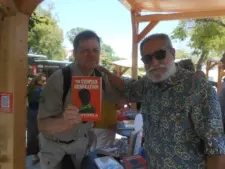

Photo: Stephen Henighan (left) presents Pepetela (right) with copies of the English translation of his novel.

. . . and the future is the past

We’ve worked with David Brookshaw on a number of projects, among them the novels and short fiction of Mozambican Mia Couto. The Utopian Generation is a book he’s known and loved—and taught—for as many years as English-language readers have been unaware of it. We sat down to ask him a few questions about translation, but also about the context in which the novel was written, and what he said confirmed our strident belief that some of our most important lessons have already been learned, and can be applied anew to our contemporary concerns.

Biblioasis: The way the novel represents the diversity of Africa and Angola, culturally, racially, and the ways the struggle for independence united people across differences, is fascinating. Can you speak to the ways this diversity makes The Utopian Generation such a dynamic novel?

DB: One of the great challenges the Angolan nationalists had to face was how to forge a sense of common purpose and identity in a country whose borders had been created artificially by competing European colonial powers in the 19th century, to the extent that an African ethnic or linguistic group might find itself divided by a hastily drawn international frontier. This was the case of the old Kingdom of the Congo, part of which found itself owing its allegiance to Belgium, and the other part to Portugal as a result of the Congress of Berlin in 1885.

When the anti-colonial struggle started to gather strength from the 1940s, the challenge in Angola and the other territories ruled by Portugal was to overcome local rivalries, which had often been stoked up by the colonial authorities. In Angola, these nationalists embarked on a journey that might lead to a sense of “angolanidade” (Angolanity). Pepetela’s novel confronts this problem through the interactions of its characters (most of whom come from different ethnic, regional, or linguistic backgrounds), and their discussions, whether in the student canteen in Lisbon, or while sitting around a campfire in the middle of the Angolan bush, or, after independence, by a beach in southern Angola or in an apartment in Luanda.

The dynamism of the novel is propelled forward not only by the changing experiences of the characters in the different historical moments and locations, and their shifting ideals (or lack of ideals), but by debate and conversation.

Photo: Angola, Portuguese troops gathered in Luanda, 1961. Designer Zoe Norvell found this photo from the American Geographical Society Library (University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Libraries) and incorporated it into the book cover.

***

Speaking of conversation . . .

We were delighted to see Olivia Snaije’s interview with Pepetela up at The Africa Report last week. Snaije outlines some of the autobiographical elements of the novel’s construction—like his protagonists, Pepetela was a student in Lisbon at the outbreak of the war, and, like two of them, he fought as a guerilla for the MPLA—and also shares the astonishing circumstances of the book’s composition and the impact of its publication:

Pepetela wrote the nearly 500-page The Utopian Generation in just one year while on a writer’s residency in Berlin. “We thought we would create paradise, but things didn’t turn out how we had thought they would,” Luanda-based Pepetela tells The Africa Report from Lisbon.

When the book was published in 1992, it became a bestseller and had the effect of a bomb due to its disillusionment and critical stance towards the corrupt post-independence government.

“My friends with the MPLA in Angola weren’t happy at all,” says Pepetela, adding that he wasn’t persecuted but that many of his friends dropped him. Today, he says, “these friends are even more critical than I was”.

The late academic Fernando Arenas wrote that The Utopian Generation was “the first novel to offer a sustained, probing, heart-wrenching as well as in-depth critique of the postcolonial national project.”

You can read the interview in its entirety here. And, thanks to Stephen Henighan and David Brookshaw, you can now read a classic of African literature in English, just thirty-two years after its original publication—thereby proving once again: backlist is fiction.

Vanessa Stauffer

Managing Editor

***

Keep up with us!

- May Our Joy Endure by Kev Lambert (trans. by Donald Winkler) will be available on September 3, 2024.

- The Notebook by Roland Allen comes out the same day on September 3, 2024.

- A Way to Be Happy by Caroline Adderson can be purchased on September 10, 2024.

- The Pages of the Sea by Anne Hawk comes out in Canada on September 17, 2024.

- Comrade Papa by GauZ’ (trans. by Frank Wynne) will be published on October 8, 2024.