The Bibliophile: We all went over our assigned word count

Want to get new excerpts, musings, and more from The Bibliophile right away? Sign up for our weekly online newsletter here!

***

In lieu of an intro: in which we pick our favourite books of the year!

***

***

Vanessa’s Picks

It Seemed Like a Good Idea at the Time may end up being the title of my publishing memoir—this would be an entry in the Act of Ignorant Enthusiasm subgenre that arises from the publication of Dan’s publishing memoir of that name, should we ever find the time to write books—and it’s what I thought when Ashley reminded us we’d agreed we’d all write about our favourite books of the year. How to choose, let alone remember what we’ve spent the last year doing, when my tasks today include the layout for a book that’s coming out in June and compiling a list of the titles we’ll be publishing between September 2025 and March 2026. The truth is that I can’t pick: they’re all good books, and I learned something from each of them, and so in lieu of the usual year-end list, I humbly present: my 2024 Weird Production Superlatives List.

Photo: The Hollow Beast by Christophe Bernard (trans. by Lazer Lederhendler), May Our Joy Endure by Kev Lambert (trans. by Donald Winkler) and Barfly by Michael Lista.

The Book with the Best First Round Cover Comps: The Hollow Beast by Christophe Bernard, translated from the French by Lazer Lederhendler

The Hollow Beast was the first book we did with Jason Arias, who received as a main objective: “Darkly comic adventure: screwball comedy with menace, a la Don Quioxte meets Who Framed Roger Rabbit? Or Thomas Pynchon done by Looney Tunes.” Jason clearly got the assignment, and it was one of those too-hard-to-choose just one, but eventually we made up our minds. (And Jason would go on to repeat this feat several more times for 2024 titles.)

The Book That Wore It Best, Typeface Edition: Barfly and Other Poems by Michael Lista

I had a tremendously good time in getting to both edit and design (aka: pulling a Steeves) Michael Lista’s long-awaited third collection. It’s typeset in Dante, an old-style serif named for its first use in an edition of Boccaccio’s Life of Dante. Featuring a weary 21st-century traveller beset by torments (buzzing flies, cultural apparatchiks, “belated Anglo-Saxon set on farms,” Anne Carson everywhere!), it’s a ruthless collection, no less so by virtue of the savage wit executed in Lista’s version of terza rima, which is not terza rima at all, but an irregular couplet that wanders and snaps shut like a trap.

The Book with the Best Second Round Cover Comps: May Our Joy Endure by Kevin Lambert, translated from the French by Donald Winkler

I didn’t have to think . . . well, at all about who to send this one to: the amazing Zoe Norvell had already knocked it out of the park with Lambert’s first two books. May Our Joy Endure is a radical departure for Lambert, featuring violence of an entirely different order: the insidious, often beautiful brutality of privilege and extreme wealth. We were slightly stumped on the first round, though Zoe landed on the typeface, Carol Gothic, which she said was inspired by Saltburn. The key: the baroque cover of Lambert-influence Michel Houellebecq’s Serotonin, which reminded us of historical markers of wealth, which Zoe made fresh with what is now a signature Lambert neon yellow.

The Book I Barely Touched But Can’t Stop Talking About: The Pages of the Sea by Anne Hawk

We shared the text files with Weatherglass, the UK publisher, and our new friend Kate Sinclair gave us that gorgeous cover in a quick second round revision, and I didn’t have to do much other than send it to print. Which has left me free to pitch this book to everyone who will listen: if you like Marilynne Robinson or Zora Neale Hurston, coming-of-age stories or novels of manners, historical fiction about untold lives, Caribbean literature, debut work, or books by brilliant Black voices, this one is for you.

The Book I Think About Every Day, and Not Because I’m Flashing Back to Typesetting 400pp In a Single Day: Question Authority: A Polemic about Trust in Five Meditations by Mark Kingwell

You know those books that split your life into Before and After? This is one of mine. How lucky am I, this and every year, that it’s my job to help make books like these and help to put them in your hands.

***

Ashley’s Picks

Love Novel by Ivana Sajko, translated by Mima Simić

Our first title of 2024 was this delightfully acerbic book—short and far from sweet, like a literary sour candy. I read it in an hour on the train while, rather amusingly, sitting across from someone reading a romance. Talk about two very different kinds of love novels! I was drawn in by the tension surrounding this unnamed couple, lovers turned new parents, caught in the deeply unfortunate circumstances of having failing careers in an increasingly unlivable society: rent is past due, they’re scrabbling for odd jobs in theaters and papers, and neither can manage to connect with the other the right way. The emotion of this story was surprisingly relatable in parts, and I’ve found myself going back to it several times this year. This Love Novel may not have a happily-ever-after, but it’s the kind of punch-in-the-jaw book that will linger with you.

Crosses in the Sky: Jean de Brébeuf and the Destruction of Huronia by Mark Bourrie

As a big history reader, Crosses in the Sky was on my TBR list from the beginning—I then had the pleasure of acting as publicist, so I shall try to keep this piece relatively impartial! What a history this is. Told in a narrative style and utilizing contemporary writings, interspersed with maps and artwork from across the centuries, Crosses in the Sky is the story of how and why the Jesuits came to “New France,” what happened when they arrived, and how these encounters have shaped settler relationships with Indigenous people to this day. I was only vaguely familiar with the story of Jean de Brébeuf, at least the bare bones of his unfortunate end, so I really enjoyed being able to dive into the full story and especially the historical context of Brébeuf’s mission and the Indigenous people who very often get overlooked when this “legend” is told.

***

Emily’s Picks

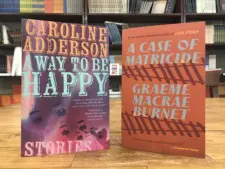

A Way to Be Happy by Caroline Adderson

Loving short stories is almost a guaranteed way to get your heart broken when you work in sales. I’ve been a lifetime lover of this genre that suits my busy brain perfectly. What’s better than a skillfully constructed piece of art you can devour before your head hits the pillow or the ice melts in your glass? So it was especially delightful to start at a press this year where the short story is celebrated and sought after. Caroline Adderson’s A Way to Be Happy was the first story collection I got to read as part of Biblioasis, and it is special. I had never read Adderson before, and was immediately embarrassed I hadn’t read her sooner. She is so obviously a master of her craft. Each story, though varied in time, place, and theme, has a core of empathetic observation. Whether she is writing about people you might avoid eye contact with on the subway, or the inmates of a 19th century asylum, she sketches her characters with a generosity of spirit and humor that shades her darker stories with hints of light. It was a pleasure to “discover” an author I should have known long ago.

A Case of Matricide by Graeme Macrae Burnet

I’m not a mystery reader, per se, but I love a good puzzle, a police procedural, and a tormented main character. While I had read Graeme Macrae Burnet’s books before, I had never read any of his books starring Inspector Gorski until I picked up A Case of Matricide. Gorski seems like a fairly average bumbling small town police inspector at first glance. He’s tired of the social constraints that have kept him where he is, and is in firm denial about his worsening alcoholism. He is also tormented by guilt over a trivial childhood transgression involving his mother’s mustard spoon, and its absence from her table condiment set presses heavily on his conscience to an alarming degree. The cycle of investigations, mustard spoon obsession, too many aperitifs and Friday night dinners crescendo to a reveal so shocking I yelped “what?,” and immediately had to reread a few pages. Throughout the whole story, Burnet expertly weaves in the meta threads he has made his signature. What if this whole story is the found manuscript of an author in the story who is a stand-in for the actual author of the story? And what if it’s a translation? How can we possibly trust the unreliable narrator who is writing and the character who is conveying his thoughts to us, the reader? The answer is never completely clear, but it’s a lot of fun to puzzle out.

***

Ahmed’s Pick

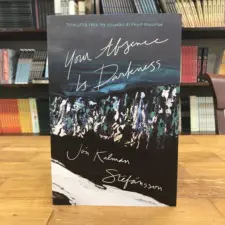

Your Absence Is Darkness by Jón Kalman Stefánsson, translated from the Icelandic by Philip Roughton

The first Stefánsson I’ve read and one that I’ll prattle on about to anyone who’ll listen. It felt like a dream. A man wakes up in a church with no memory of who he is let alone how he got there with a mysterious man who could be Death or the Devil. I was absorbed from the start. Trying to understand himself, the narrator winds up with a large cast of characters who love deeply in a cold, small part of Iceland where everyone is connected and haunted by their pasts. Stefánsson is able to make you care for every one of them. We move through lives across generations and everyone’s story is so beautifully realized. Reading it felt like I was discovering this strange and wonderful thing and I wanted to stay for as long as I could. But what really gets me about this book is the music throughout it, which unites them and shapes the story. Stefánsson has written a ballad as a novel.

***

Dominique’s Picks

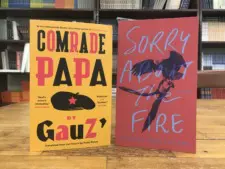

Sorry About the Fire: Poems by Colleen Coco Collins

This is a startlingly good collection, head-and-shoulders above most recent poetry because it does more than simply put words to use, but actually revels in the strangeness of language. Words from the book will suddenly appear to me while I’m doing mundane tasks like washing the dishes—words like haustoria, dehiscence, weft . . . And I love that these poems encourage a thousand slow re-readings to disinter their thousand possible musics. I read almost one hundred poetry collections this year, and nobody writes like Collins.

Comrade Papa by GauZ’, translated from the French by Frank Wynne

Somehow, I hadn’t heard of GauZ’ before starting work at Biblioasis, but the first few chapters of Comrade Papa immediately felt like a revelation to me. As soon as I finished it, I picked up Standing Heavy. And I intend to read these in their original French because, as someone who’s tried her hand at French to English translation a number of times, Frank Wynne’s talent for transcribing style seems inexplicable—I’m so curious to know what Anouman’s malapropisms (“the lumpenproletariat,” “the retching of the earth,” etc.) are like in their original French. Anyone who isn’t reading GauZ’ (and Frank Wynne) are seriously missing out.

***

Dan’s Picks

A decade or so ago, Mark Medley expressed exasperation in the Globe and Mail over my general enthusiasm for our list, writing that “in almost a decade writing about the Canadian industry, [he’d] never met a publisher so convinced of the greatness of their every book; [he’d] grown exasperated with [me] more than once when [I] told [him] that the slate of books the company was about to publish was the “best” [we’d] ever produced.” It seems, Medley claimed, I say the same thing every year.

Perhaps this is true, and perhaps this is true because our list has gotten better every year. Though I fear every year might be the high-water mark, and that there may be no way to continue to sustain what we’ve cobbled together, somehow, with the help of Vanessa and John and everyone else who makes Biblioasis what it is, we pull it off. One of the lessons of this year is that publishing is hard; and, harder to accept than that, that it will always be so; but another is that there’s reason to be constantly hopeful. Despite appearances, we’re nothing if we’re not eternal optimists.

The problem with putting together a year-end list of my favourite books is that, as Mark suggests, most of our books are, in fact, favourites. And never has there been a year where this is more the case. I loved Ivana Sajko’s Love Novel (translated by Mima Simić) for the way that it burned, furious, at the injustices of the world, the only things keeping me from suffocating its life-giving humour and compassion; I loved Alex Pugsley’s The Education of Aubrey McKee for its playfulness and the way that he blended forms in this funny, moving, brilliantly-timed coming-of-age novel; discovering the work of Jón Kalman Stefánsson in Philip Roughton’s masterful translations has been a revelation that has subtly shifted my relationship to word and world, with the exceptional Your Absence Is Darkness only the first of many books by this Icelandic author you’re going to be seeing on our list over the coming years: in a world that continues to shift darker, his words bring much-needed light. I took great pleasure in Richard Kelly Kemick’s inventive horseplay in Hello, Horse; immense joy from Donald Winkler’s fine translation of Kev Lambert’s brilliant third novel, May Our Joy Endure; and was made very happy indeed to finally be able to work with Caroline Adderson on a very fine new collection of stories, A Way to Be Happy. And then, to round out the year, there was Graeme Macrae Burnet’s subtly sideways A Case of Matricide, which has left me feeling shadowed by my own Gorski-like doppelganger all year. And that’s just (most of!) our fiction list!

Our list is not just getting better; it’s also getting broader. One of the things I am most proud of as a publisher is the breadth of our list, that the best fiction and nonfiction rub shoulders almost every month. The past year showed this as well as any year in our history, with Mark Bourrie’s National Bestseller Crosses in the Sky continuing its stylish reconsideration of the history of first contact in Canada; Roly Allen’s The Notebook forcing us to come to terms with the way the smallest, most unsuspecting of inventions has radically helped to reshape the world and how we relate to it; Mark Kingwell’s Question Authority, his most ambitious work of philosophical analysis, by my reckoning, in decades, offering possible remedies for our current addiction to conviction, and a reminder that it’s often in our shared vulnerabilities that we find most strength; and Bruce Whiteman’s Work to Be Done shows him to be one of our most perceptive and elegant critics.

And I haven’t even talked about our poetry list, the Best Canadian series, or the Christmas Ghost Stories (which are celebrating their tenth anniversary this year!). Though, backlist being a fiction, there’s time (despite the end of my allotted word count) yet: if I’m going to make an early New Year’s resolution, as a reader and publisher, it’s to be less prone to the pressures of what’s new and hyped: expect a lot more, in future Bibliophiles, dwelling on the riches of the past, which are as new to you, if you’ve not had the pleasure of reading them yet, as anything else will be.

***

In good publicity news:

- Three Biblioasis books made the CBC Best Canadian Fiction of 2024 list: The Pages of the Sea by Anne Hawk, A Way to Be Happy by Caroline Adderson, and May Our Joy Endure by Kev Lambert (trans. Donald Winkler).

- On Browsing by Jason Guriel was mentioned in the New Yorker.

- The Notebook by Roland Allen appeared in the Globe and Mail’s 2024 Gift Guide: “Enjoy this dive into the act of jotting things down.”

- Seth’s Christmas Ghost Stories 2024 were reviewed in the Literary Review of Canada’s Bookworm newsletter: “Each story can add a delightful tinge of darkness to any booklover’s stocking.”