End of November: Major Media Round-Up!

IN THE NEWS!

GLOBE 100 BEST BOOKS OF THE YEAR

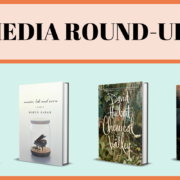

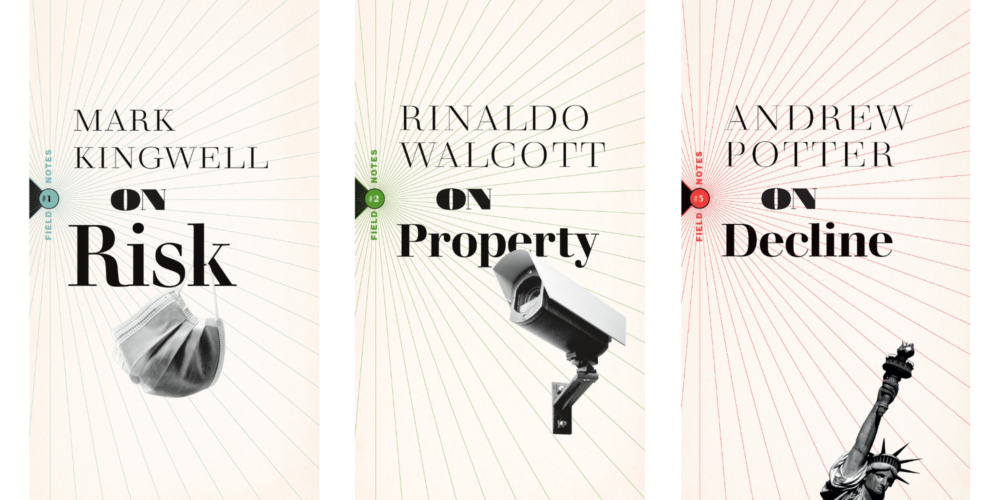

On November 29, The Globe and Mail announced the ‘Globe 100’, their 100 best books of the year. We are delighted to have three Biblioasis titles included this year, Doireann Ní Ghríofa’s A Ghost in the Throat (June 1, 2021), Marcello Di Cintio’s Driven (May 4, 2021), and Rinaldo Walcott’s On Property (February 2, 2021)! You can view the whole list here.

Order On Property here!

Order Driven here!

Order A Ghost in the Throat here!

FOREGONE

Foregone by Russell Banks (March 16, 2021) has been listed by Kirkus as a Best Fiction Book of the Year! The list was published on November 15, and can be found on their website here.

Kirkus had originally reviewed the book on March 2, 2021 saying that the book was:

“a challenging, risk-taking work marked by a wry and compassionate intelligence.”

Order your copy of Foregone here!

THINGS ARE AGAINST US

Lucy Ellmann’s Things Are Against Us (September 28, 2021), has been included in the ‘Best Gift Books to Give 2021’ by the Chicago Tribune! The guide was published on November 24. You can view the whole guide here.

Christopher Borrelli says:

“[Lucy’s] working in a tone familiar to lovers of E.B. White and Norah Ephron—knowing, funny, exhausted. Subjects include the patriarchy, staying home and underwear (“Bras: A Life Sentence”).”

Order your copy of Things Are Against Us here!

Music, Late and Soon (August 24, 2021) by Robyn Sarah has been included on the CBC Books ’20 books for the music lover on your holiday shopping list.’ The list was published online on November 29. See the full list here.

Sarah was also recently named a finalist for The Mavis Gallant Prize for Non-Fiction. The following statement was provided by the jurors:

“Sarah splices the narrative of her belated return to piano lessons with memories of her development as a promising professional musician. Sarah understates her musical talent but the facts speak for themselves. At twenty-four, however … she abandoned music as a profession to become a poet and literary editor.

Sarah calls her book “a musical autobiography” but it is far more than that. It is a deeply intimate exploration of the artistic process by a writer of remarkable maturity and poise.

Unfailingly, her prose remains centred, rooted in humility, never drawing attention to itself. Her every word feels thoughtful, honest, and true. With this book, Sarah demonstrates that a life pursued artistically, when done so with sincerity and integrity, is a life lived spiritually, no matter what the discipline. Concert halls might be poorer for her career choice, but the literary world can count itself richly blessed.”

Order your copy of Music, Late and Soon here!

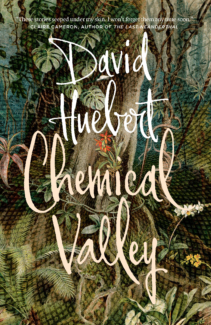

CHEMICAL VALLEY

Chemical Valley by David Huebert (October 19, 2021) has been reviewed in Atlantic Books! The review was published today on November 15, and can be read on their website here.

Reviewer Chris Benjamin said,

“Huebert is a gifted short story writer. His characters do contain multitudes, each story a set of worlds. Collectively, they reflect our times, and help us contemplate the most dire of threats to our singular habitable planet.”

David Huebert was interviewed on the @Risk Podcast! The episode was posted on November 18, and can be listened to here.

David Huebert was also interviewed about Chemical Valley (October 19, 2021) by Keri Ferguson in Western News! The interview was posted on November 25. You can read it here.

Order your copy of Chemical Valley here!

On November 22, it was announced that Doireann Ní Ghríofa’s A Ghost in the Throat (June 1, 2021) is a New York Times Book Review Notable Book of 2021! You can view the whole list here.

Reviewer Nina MacLaughlin said,

“This book comes from the body, from the ‘entwining strands of female voices that were carried in female bodies.’ The sound of the female voice, the aural texture of A Ghost in the Throat, is part of its deep pleasure.”

It was also announced on November 22 that A Ghost in the Throat is a Kirkus Best Book of 2021! You can view the whole list here.

The original starred review reads,

“Lyrical prose passages and moving introspection abound in this unique and beautiful book.”

The NPR Books We Love list (formerly Books Concierge) was announced on November 24, and both Doireann Ní Ghríofa’s A Ghost in the Throat (June 1, 2021) and Mia Couto’s Sea Loves Me (February 23, 2021) are included! You can view the whole list here.

Ann Powers says of A Ghost in the Throat,

“Intensely poetic and freewheeling and connecting the bodily details of mothering and erotic love – “female texts” – to linguistic hierarchies and erasures, this book creates its own form: a critical biography of the body, of bloodshed and babies born, of the word made flesh.”

Order your copy of A Ghost in the Throat here!

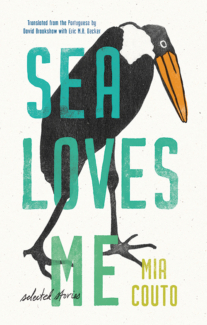

SEA LOVES ME

Mia Couto’s Sea Loves Me (February 23, 2021) was also included on the NPR Books We Love list from November 24! You can view the whole list here.

Thúy Ðinh says of Sea Loves Me,

“As with his natural affinity toward cats, Couto’s stories — deftly translated by David Brookshaw and Eric M.B. Becker — represent graceful attempts to transcend barriers between the colonizer and colonized, native and settler, human and animal, matter and antimatter.”

Order your copy of Sea Loves Me here!

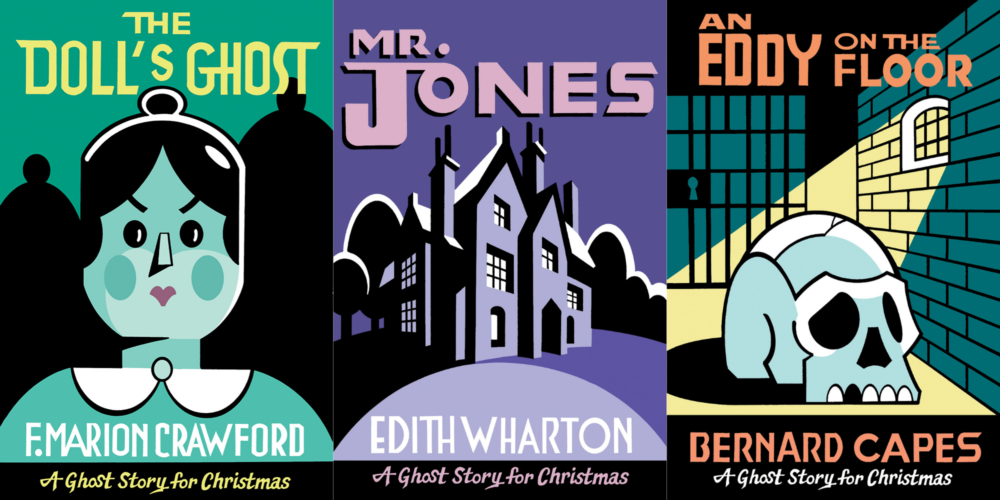

CHRISTMAS GHOST STORIES 2021

Seth, the designer and illustrator for Biblioasis’ Christmas Ghost Stories (October 26, 2021) was interviewed on CTV Kitchener! The interview aired on November 24. You can watch it here (beginning at 21:35).

The Doll’s Ghost by F. Marion Crawford from Christmas Ghost Stories (October 26, 2021) was featured in a reading on the Christmas Past podcast! The episode was posted on November 26. You can listen to it on their website here.

Host Brian Earl said,

“The great thing about each passing season is the chance to discover something new that may go on to become a new favourite. That old and largely forgotten tradition of Christmas ghost stories is fertile ground for anyone digging for a spooky festive treat from a bygone time.“

Christmas Ghost Stories (October 26, 2021) was also reviewed on the Total Christmas Podcast! The episode was posted on November 21. You can listen to it on their website here (review starts at 34:00).

Host Jack Ford said,

“These books are just delightful … and the illustrations are just—shall I say delightful again?”

Order the Christmas Ghost Stories 2021 bundle here!

BEST CANADIAN 2021 SERIES

The Best Canadian 2021 Series has received a great review in the Toronto Star by Steven Beattie. The review was published online on November 26. You can read the review here.

Beattie writes,

“All three of these volumes have much to recommend, though the stylistic virtuosity on display in Best Canadian Stories 2021 testifies most explicitly to a range of writing being produced right now. But it is Thammavongsa’s poetry selection that provides the most startling and memorable moment. David Romanda’s poem “We Really Like Your Writing” manages something in five short lines that few of the other writers in any of these anthologies even attempt: it makes its reader laugh out loud. And that has to qualify as one of the best outcomes from a year of uncertainty, trouble, and strife.”

Order the Best Canadian 2021 Series bundle here!