All Hands On the Loading Dock:

An Interview with Kathy Page

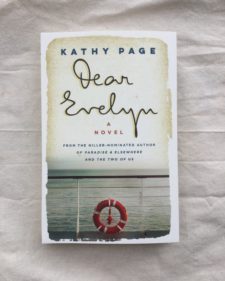

The Biblioswains were busy this morn with boxes and boxes of books, among them Dear Evelyn, the latest from Kathy Page. This epic love story steams into a port near you on September 4. We sat down with Kathy to find out more about the book Kirkus Reviews calls “A searching, and touching, depiction of the places where married lives merge and the places they never do.”

The Biblioswains were busy this morn with boxes and boxes of books, among them Dear Evelyn, the latest from Kathy Page. This epic love story steams into a port near you on September 4. We sat down with Kathy to find out more about the book Kirkus Reviews calls “A searching, and touching, depiction of the places where married lives merge and the places they never do.”

For newer readers who may not be familiar with your work, can you tell us a little about yourself and your writing?

My father was a great reader, and my mother had a very definite way with words; both encouraged me to develop an already over-active imagination, and as a child I read and wrote voraciously, without realizing that I was laying the foundations for something I might end up practicing as a profession. I studied literature as an undergraduate and afterwards began my first book in a continuing education class. Since then I’ve written mainly fiction: numerous short stories, eight novels, and been listed for the GGs, the Giller and the Orange Prize. As a writer, I’m drawn to complex characters, and to people in difficult predicaments or who have to make hard choices. I’m interested in transformation, and how it occurs. I like to explore questions of some kind.

I feel very lucky to be able to use my imagination and play with words on a daily basis, to craft stories, to work with others learning to do the same (I teach at Vancouver Island University), and, of course, to connect via those stories with readers: I’m fascinated by the writer/reader relationship. I’ve been based on Salt Spring Island in BC since 2001; before that I lived mainly in London (UK).

Dear Evelyn sweeps across history, from World War I to the present day. You mention in the acknowledgements how letters from your father to your mother were helpful, as well as other extensive researching activities—yet the novel is still so character-driven! How did the research impact the writing?

You’re absolutely right that the characters are what drive this book. But in order to understand them, write them, and know the story I had to find out a great deal. I often do a lot of research and enjoy finding out about things beyond my own experience. Sometimes the research will shape or change how I think about the book. Dear Evelyn was very much inspired by the love letters my father wrote to my mother during the Second World War, which I read when my parents were in their nineties and in a very different situation. Reading those letters at that point in time made me intensely curious as to how a marriage between two very different, very young people—one that had begun with such romance and drama—might transform itself over a long period of time. I couldn’t explore the detail of that without becoming familiar with the social history of the ―between-the-wars‖ period in the aftermath of the First Word War, when my characters had grown up, and then I found myself immersed in certain bits of WW2, and then in the postwar period, and the nineteen sixties and seventies… There was a lot of detail to take in, but, to answer your question (I hope): the research is in the service of the characters and the story; it is part of them and part of what makes them seem real. In the end, whatever I have learned becomes the context of their lives and desires and possibilities. Once I am immersed in the story, it stops being research. It’s just their reality.

Anyone who has read your previous work (I’m particularly thinking of Alphabet) will note a range in subject matter, to say the least. Despite this, are there themes or central concerns in your work that you hope readers take away?

I like to do something very different with each book, whether that’s in terms of the territory it explores or the way the material is approached. Previous novel protagonists include a man serving life for murdering his girlfriend (Alphabet), a young mum with a special needs baby (Frankie Styne and the Silver Man), a middle aged academic who suffered severe burns to her face in childhood (The Story of My Face) and a driven, ambitious paleontologist (The Find). My short fiction is also varied: sometimes realist (The Two of Us), sometimes experimental or fabulist (Paradise and Elsewhere). I think what ties it all together as a body of work is a strong interest in human connection, in relationships, especially difficult, imperfect relationships—the kind that a therapist perhaps might not recommend, but in which, it seems to me, many or even most of us are at one time or another passionately involved.

Dear Evelyn fits this pattern. It’s another new thing: a book focused on a single seventy-year relationship and also one that’s both historical and personal, so very much a first for me; it is also a continuation of my ongoing exploration of what it is we do with, and to, each other… I’m certainly not against positive change, but it seems to me that we sometimes forget that even difficult, seemingly dysfunctional relationships may be precious and sustaining—and sometimes we just don’t care about what is fair or reasonable.

Harry and Evelyn certainly spat and bicker, yet also undeniably love each other. And then there is the ending—without giving too much away, do you consider this a hopeful book?

It depends on how you think about what happens, and your beliefs about love and relationships. I hope readers will experience Harry and Evelyn’s story and then decide for themselves. But I will say that although my books often tackle difficult material, I think of myself, and of my work, as essentially optimistic.

The conflict between Harry and Evelyn is the book’s backbone, yet I always felt Evelyn’s tempestuous relationship with her parents lurking in the background, informing how she interacts with Harry. Am I off in that? Can you speak to that at all?

I’m glad that came over! Evelyn’s anger towards her alcoholic father, her horror at the manner of his death, and her struggles with a sometimes over-protective mother—as well as their poverty—are all behind how she behaves, what she wants and chooses, and what happens in her marriage. I’m glad the reader can see this, and so have a compassionate sense of how her sometimes outrageous behaviour is driven by half-buried fears. She of course does not see this; she grew up in an era when people did not readily think about why they felt and acted as they did, try to change it, or share their more difficult and complicated feelings with others. They did what they could, or what they were driven to, and that was pretty much the end of it… In a similar vein, at the beginning of the book Harry’s mother deals with post-natal depression—very successfully, as it happens, but without any professional intervention.

What are you reading right now?

I’m reading and very much admiring the Melrose novels by British writer Edward St Aubyn, and am about half way through the series. Horrifying, funny and brilliantly written. Next up is Shyam Selvaduri’s The Hungry Ghosts.

An Interview with Kathy Page

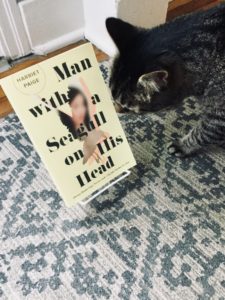

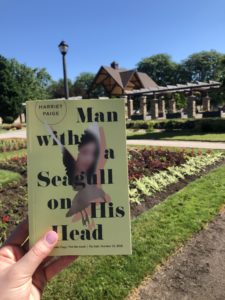

As you head for the beach this long weekend, consider the story of Ray Eccles, a city clerk “past the age when anything interesting was likely to happen to him,” who one day is struck on the head by a dying seagull and wakes up compelled to obsessively paint the last thing he saw before he was knocked out: an unknown woman on the beach. What happens next is anything but uninteresting: Ray’s paintings are discovered by husband-and-wife Outsider Art dealers and quickly take the art world by storm. Meanwhile Jennifer, his anonymous muse, ponders the surprising turns and odd connections that characterize a life.

As you head for the beach this long weekend, consider the story of Ray Eccles, a city clerk “past the age when anything interesting was likely to happen to him,” who one day is struck on the head by a dying seagull and wakes up compelled to obsessively paint the last thing he saw before he was knocked out: an unknown woman on the beach. What happens next is anything but uninteresting: Ray’s paintings are discovered by husband-and-wife Outsider Art dealers and quickly take the art world by storm. Meanwhile Jennifer, his anonymous muse, ponders the surprising turns and odd connections that characterize a life.