The Bibliophile: A Good Short Story

Want to get new excerpts, musings, and more from The Bibliophile right away? Sign up for our weekly online newsletter here!

***

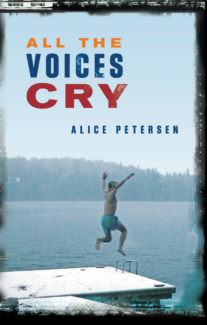

The make-up of Best Canadian Stories 2025

“What makes for a good short story?” So asks this year’s editor Steven W. Beattie, in the opening lines of his introduction to Best Canadian Stories 2025. It’s a tough question, even for someone who’s been entrenched in short stories from all kinds of print and online publications for the better part of a year. Is a good story technically brilliant? Poignant? Does it make you feel strongly, laugh or cry? Is it a story you read over and over again without really knowing why, but goodness, just starting it one more time still fills you with anticipation, and leaves you thinking, wow. For my own part, despite several years of assisting with the production of these books, and my own forays into short story writing with varying success, I don’t have a clue how to definitively answer that kind of question. At the very least, however, I do know what makes for making an anthology of short stories.

The role of editor for these anthologies is not one I envy, but the process of watching them come together piece by piece over the course of several months, slowly and then in something like a torrent as production moves forward, is kind of magical. There is, of course, the harvesting of all of these wonderful online and print publications—and here I’ll say to those editors who would like their journals or magazines to be considered: please send issues! (Apologies to those reading who have already endured frequent follow-ups.) The deployment of acceptances to writers is almost always the nicest part of this process, whether they’ve been included before, like our pals Kate Cayley and Mark Jarman, or are new to the series, like Cody Caetano or Kawai Shen.

I’ve read their stories many times during the course of selection: thumbing quickly through the pages as journals arrive at our office, then as they come to me again in Word Docs, and PDFs from excited contributors, and again through several rounds of proofing, until finally, I get to read them in their final form as a finished book that now has a place on my own shelf at home. There is a dazzling range of short fiction represented in these pages—Saad Omar Khan’s “The Paper Birch,” a story of a young boy’s belief and determination to help cure his sister’s cancer; or “Couples’ Therapy,” Christine Birbalsingh’s vignette of a woman whose couples’ therapy session goes frustratingly wrong; or “Funny Story,” Liz Stewart’s non-stop comedic trip to the hospital resulting from an unfortunate bedroom incident. The one I’ve chosen here today is Glenna Turnbull’s “Because We Buy Oat Milk.” I can’t say I know what exactly a “good short story” is, but I can say without a doubt that I’ll be enjoying each of these stories many more times in the years to come, as I have with all of our past BCS anthologies.

And I would be a terrible editorial assistant if I didn’t add that BCS comes in a delightful bundle with the other anthologies, a perfect gift for the literary-minded!

Ashley Van Elswyk,

Editorial Assistant

***

Because We Buy Oat Milk

Glenna Turnbull

Each morning starts with a cup of coffee, because who can function without that first hit of caffeine—but not too much caffeine so just a half-caf latte for me that I make at home because it’s cheaper and doesn’t create more waste with those takeout single-use cups, and not with cow’s milk because cow’s milk was meant for baby cows, that’s what Eric says, and never almond milk, because, well, Eric is convinced the almond milk industry is run by the mafia and uses too much water—water that Eric would rather secretly snake out when nobody is looking, late at night in well-hidden hoses that slither into the cedar hedges they tell you never to plant in the Okanagan because of the drought and the fires that rage here—fire season, heat domes, we are doomed, but especially doomed if we put cow’s milk in our coffee so we only buy oat milk because mares eat oats and goats eat oats and little lambs eat ivy and the ivy grows up on the side of the house, its tendrils gripping on for dear life but Eric says it will crumble the bricks if we leave it but we can’t kill it because its leaves are filters for all the carbon monoxide we are producing, the greenhouse gases which have very little to do with the greenhouse Eric built in the backyard which then became my job to tend, to make sure the bugs don’t get in and if they do then I have to kill them because it’s okay to kill the bad bugs just not the good bugs and then everything gets watered with more of the water we’re not supposed to be using but it’s okay, because if we grow stuff in our yard then we aren’t contributing to the greenhouse gas problem by having to drive to the store. Except to buy oat milk. We don’t grow oats.

Eric leaves for work like he does every weekday at ten to seven in the morning in his orange Ford pickup truck and I don’t point out the amount of carbon monoxide he puts into the air as he lets it sit idling in the driveway for five minutes to warm the engine up or that the truck burns oil or that rust really isn’t orange at all but more of a brown colour, brown like the leaves that the house-eating ivy turned after the heat dome we had last summer, or maybe it was the wildfire smoke, so thick we couldn’t see the houses half a block away, that made its colour change, and I had to keep the kids indoors, letting them play on the computer or build things with Legos as they watched television so they wouldn’t be breathing that brown into their lungs—lungs already strained from wearing masks in school all year long—well, that Ethan and Emma had to wear but not Ellie because I kept Ellie home with me as Eric said she didn’t really need to go to kindergarten, that I could teach her way more at home and he didn’t want her first experience of school to be scary, with everyone hidden so only their eyes showed what they were thinking, which I actually kind of liked in a way because it is harder for most people to lie with their eyes than it is with the rest of their face. I try to always believe what I’m saying is really true and make sure my eyes remain fixed straight ahead as I talk but not too fixed because if I stare back too hard, then Eric will know if I’m lying, right?

Ellie started grade one this fall and with the cost of food and the interest rates climbing faster and higher than the house-swallowing ivy, Eric says I need to go back to work full-time because really, how long does it actually take to do bookkeeping for my few remaining clients since Covid coughed up the rest of their businesses like a giant hairball and what else do I do all day but run errands and make meals and go grocery shopping for oat milk and squish the bad bugs in the greenhouse? He thinks I do nothing because he came home from work early one day last spring sick with Covid and discovered I had the TV turned on while making supper so he is convinced I sit around the house all day watching soap operas but really it’s only General Hospital and I’ve been watching that since I was a child when I’d sit underneath my mother’s ironing board and she’d forget I was there and I learned about way more things than I would have if I’d been in kindergarten, things like affairs and passion and love and betrayal and how to lie without looking like you’re lying when you say things like, yes, I still love you, or I couldn’t be happier, or of course he’s your son! It’s also where I first learned about abortions.

Making lunches, no peanut butter for Ellie as someone in her class has a nut allergy, so I put in cucumbers and carrots from our greenhouse and yogurt from the same store we buy the oat milk from and not the soy yogurt that is so gross nobody will eat it, but the one with the catchy jingle in the commercials that play during General Hospital. Eric says it’s okay if there are still a few cows on the planet trapped working in the dairy industry, enough to make the cow’s-milk yogurt he likes which comes in the little plastic containers that kids eat with little plastic spoons that all get thrown in the garbage when they’re half-done because, really, who has time at their school to clean out all those little plastic containers and wash all those little plastic spoons and then haul them all to the recycling bin along with all the plastic bags everyone’s sandwiches came wrapped in, but it’s okay because we don’t have plastic straws anymore and Ellie, Ethan, and Emma can grow up teaching their children to only drink oat milk as they wander through the barren spaces where old-growth forest once stood on Vancouver Island, or the burnt black toothpick-like Okanagan woods that were once green, a different tone of green from the greenhouse-plant green or the ivy green or the greenhouse-gases green, a colour they might only read about in books if there are still books—oh please let there still be books!

Drive the kids to school because we’re too late to walk, pumping more exhaust into the air, then it’s time to walk Einstein—Einstein, who doesn’t live up to the potential of his name, because Eric said if we got a dog it simply had to be a doodle because, well, everyone else has doodles now as they don’t shed which makes them so much cleaner but you have no idea what happens when a doodle like Einstein sticks his head into the water dish and the hairs surrounding his muzzle soak up the liquid faster than a cannula pump, his fur like an old-fashioned wringer mop that hasn’t been wrung out so he leaves a trail of water across the kitchen floor like a greenhouse slug that has to be squashed, then I need to get out our Bee mop with its artificial sponge head to clean up but Eric says all this helps to keep our kitchen floor clean—Mr Clean, Lysol, Vim, all the cleaners lined up all neatly hunkered in their bunker in a trench under the sink, a little army in their plastic bottles full of chemicals and perfumes that mingle with the Downy Unstoppables poured into the laundry so our clothes stink like an old woman’s purse for weeks instead of only days because Eric likes to smell perfumy-clean, especially after standing out back behind the greenhouse smoking the cigarettes he thinks I don’t know about but I do because really, how can you sleep with someone and not smell the nicotine oozing out of every pore in his body when he sweats on top of you even when you say it isn’t a safe time and he needs to stop and that you really mean it, then you lay under the blankets and find you can’t sleep because your mind won’t stop thinking about the Brazilian rainforest or Fairy Creek or your extended family in Ukraine being blown up in their sleep or oil companies announcing record billion-dollar profits at the same time we’re told we aren’t reducing our carbon emissions enough to keep global warming under 1.5 degrees or the unwanted life that might be brewing in your belly and it’s sweltering in here because Eric has turned the mattress pad up to high and he is radiating nicotine-infused heat like the atomic waste they keep burying around the world created by all the clean energy nuclear power plants that aren’t really clean or leafy green at all, forging their power out on those long straight lines that span across the sky like lines on a musical staff or lines on a street, lines that get crossed, lines across a Covid test. Or a pregnancy test.

I caught Eric siphoning gas out of the old lawn mower because it’s now over two dollars a litre, and he got mad when I said it should cost even more so more people will park their cars and ride their bikes to work but not the electric bikes because Eric said they use child labour to make the batteries and here in North America our children can’t even pick up their toys, and if I step on one more piece of Lego I might just throw them all in the garbage or at least the recycling bin because they’re made of plastic but the recycling company says you can’t recycle plastic toys so what do you do with the unwanted Legos or the children who won’t pick them up and what do Americans do now that Roe v. Wade is gone and they can’t afford a fourth child?

Separate the whites from the colours but then add them in anyway because you know Eric gets upset if you waste energy running the washing machine when it’s not a full load and then climb back up the basement stairs, careful to watch for Einstein’s water marks and navigate the small pieces of Lego that wait like bees to sting your feet except the bees are disappearing, and what will pollinate the fruit trees so heavily sprayed with pesticide for codling moths and aphids and leaf curlers, hair curlers, curling irons, ironing board, soap operas, lying, lying with my eyes to Eric when he asked this morning if my period came yet.

O Canada, our home and native land, Native land, Native, First Nation, residential schools and treaties and promises, here, have a blanket that wasn’t properly separated in the laundry to cut down on the washing bill, wrap your baby up tight and rock it to sleep, deep sleep, to sleep my baby, to sleep forever, my Canada, O Canada where I thankfully still have control over my body so when my doctor confirmed it was no bigger than a garden slug or small piece of Lego, I could choose.

At the Kelowna General Hospital, which is very different from General Hospital, I walk past the protesters who circle around and around outside its doors like privileged children who don’t have to pick up their toys, around and around like a merry-go-round, round and round the mulberry bush, each carrying signs that tell me I’m about to become a murderer and will burn in hell, pop goes the weasel, that Roe was a hoe and Wade, being a man, knew oh so much better, then I check into the same front desk that I checked into while in labour with each of my three kids before the elevator whisked us up to the third-floor delivery rooms but I don’t head to the delivery room today—instead, I go down a different hallway to the special area set aside for all of us careless flippant about-to-be murderesses who just went and got ourselves pregnant again because it’s always our fault it happens (didn’t you say no?), and I put on the robe that ties in the back (but did you really mean it?), and I want to leave my socks on because it’s cold in the room, but the nurse says they have to come off because somehow having warm feet might interfere with the ability of the cannula pump to suck this fetus out of me, this little Lego piece that doesn’t fit into our family plan, family planning we learned in high school—how to put condoms on bananas and how to say no, say it like you mean it, say it with your eyes, just say no, to just say no, to say, to just say. No!

I lie there patient as a cactus waiting for my turn to come around and I stare straight into her eyes as I tell the nurse yes, I have a lift home, because it’s not a complete lie—I don’t tell her I’m the driver and that I need this to be done in time to meet Ellie, Ethan, and Emma at the school gates with Einstein on his leash and a smile on my face as if everything is fine fine fine even if my eyes are bloodshot and I reek of sadness.

Back at home, I send Ethan out to the greenhouse to pick cucumbers and tomatoes and turn on General Hospital so my brain can switch off, my cramping body slumped across the couch and I listen as Ellie and Emma giggle upstairs sneaking pieces of their Halloween candy, and even though I keep thinking about the poison and chemicals they’re pouring into their little bodies, the artificially flavoured sugar that’s coloured with products I can’t even pronounce, I can’t seem to rally enough to stop them and it’s not until Einstein starts whining at the back door that I finally give in and begin to peel myself up off the sofa, the bulky blood-soaked pad between my legs feeling thick as a hotdog bun.

I swing my legs over the edge of the cushions and my foot comes hammering down onto a tiny piece of Lego no bigger than a small garden slug, and the full pain of the day takes over, thick as a blanket of forest fire smoke, swaddling me in brown, crumbling like a brick house, taking me down down down.

—from PRISM international

Glenna Turnbull’s short fiction has appeared in PRISM international, Riddle Fence, The New Quarterly, Cliterature, Luna Station Quarterly, and, once upon a time, in Room. She was shortlisted for the TNQ Peter Hinchcliffe award and earned an honourable mention. She was also shortlisted for EVENT’s Let Your Hair Down speculative fiction contest, and in 2023 won PRISM’s Jacob Zilber Short Fiction prize. Her non-fiction has appeared in HomeMakers, Reflex, the Same, and Okanagan Life and been read on CBC radio. She put herself through university by taking one course per semester while raising two boys as a self-employed single parent. She graduated from UBC Okanagan at the age of fifty with a BA majoring in English and creative writing. Glenna had a weekly column called Arts Seen that ran for more than a decade. She currently works as a freelance writer, photographer, and stained glass artist and lives in Kelowna, British Columbia, with her two dogs and grown children. Her story “Because We Buy Oat Milk” came spilling out of her one morning as she sat drinking coffee, listening to the CBC news, and worrying about the state of our planet. Her debut novel, Finding Sally’s Cove, is forthcoming with Breakwater Books.

***

20 Stores for 20 Years: Upstart & Crow

We return to our 20th anniversary celebration of 20 independent stores that have supported us with Upstart & Crow, a dream of a bookstore on Granville Island. Not only thoughtful booksellers, the folks at Upstart & Crow also run a creative studio and literary incubator. Ian Gill, one of U&C’s founders, chose The Power of Story by Harold R. Johnson as the Biblioasis book that moved him the most, and our publisher Dan shared how Upstart and Crow inspires his own practices as a bookseller.

Dan on Upstart & Crow: “I have owned my own bookstore for more than a quarter of a century and have ordered almost every single title that lines its shelves: I still walk through those doors expecting something unexpected that may change my life (& there often is). I’ve not yet had the pleasure of walking through Upstart & Crow’s doors, but I already have a sense of how transformative that will be: their commitment to literary community, to excellent books, to writers in translation, and to rethinking how a bookstore should be has been inspiring, and strengthens my hope for the future of bookselling in this country. I have nothing but respect and gratitude for Robyn, Zoe, Ian, and the rest of the U&C crew, and all of us at Biblioasis look forward to seeing where they take bookselling next.”

And here’s why Ian Gill thinks The Power of Story is a must-read: “Oh how I wish Harold R. Johnson hadn’t left us so early, how I wish I could be in conversation with him again, maybe this time around a campfire. Luckily, Harold bequeathed us The Power of Story, a campfire inspired meditation whose subtitle says it all: On Truth, the Trickster, and New Fictions for a New Era. It is first among many brilliant Biblioasis books that we carry at Upstart & Crow. To share it with others is a small but important way of keeping the conversation going. We miss you, Harold.”

Photo: Co-founder Ian Gill shows off his Biblioasis pick, The Power of Story: On Truth, the Trickster, and New Fiction for a New Era by Harold R. Johnson.

***

For the Holidays…

Looking for your next great Biblioasis read? Struggling to pick the perfect gift for a book-loving loved one?

Then you’ll be thrilled to find out that our 2025 Subscription Club boxes are here! Fiction, Nonfiction, Poetry, Translation, and Surprise—pick a box for yourself or as a gift to someone else, and choose your desired forthcoming titles (or be brave and let us make the choices!)

***

In good publicity news:

- The Notebook by Roland Allen was featured in The New Criterion: “A delightful mix of material and intellectual history.”

- A Case of Matricide by Graeme Macrae Burnet was reviewed in the New York Times: “You can gulp down A Case of Matricide in one sitting, as the prose style seems to demand. But linger over Burnet’s novel, and its real pleasures emerge.”

- 1934: The Chatham Coloured All-Stars Barrier-Breaking Year by Heidi LM Jacobs was featured in an episode of CBC Ideas on the team.

- Seth’s Christmas Ghost Stories were featured in Boing Boing: “This year marks the 10th anniversary of these beautifully designed pocket-sized books . . . As someone who has collected these books for years, it’s exciting to get three more of these pocket-sized treasures.”

- Mark Kingwell, author of Question Authority, was interviewed in The Jacobin and The Varsity, and for a episode of TVO’s The Agenda.

- Anne Hawk, author of The Pages of the Sea, was interviewed about the book on CBC’s The Next Chapter.