Rave Reviews for Biblioasis Titles!

IN THE NEWS!

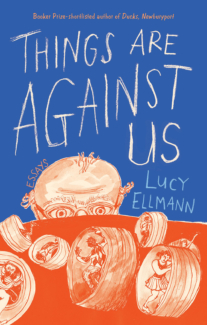

THINGS ARE AGAINST US

Lucy Ellmann’s Things Are Against Us (September 24, 2021) received another rave review in The Guardian! The previous one was in the Sunday Observer. This Guardian review was published online and in their print issue on July 3, 2021. You can read it on their website here.

Lucy Ellmann’s Things Are Against Us (September 24, 2021) received another rave review in The Guardian! The previous one was in the Sunday Observer. This Guardian review was published online and in their print issue on July 3, 2021. You can read it on their website here.

Reviewer Catherine Taylor wrote:

“Ellmann’s polemic is a medley: a wickedly funny, rousing, depressing, caps-driven work of linguistic gymnastics hellbent on upbraiding the deleterious forces of the prevailing misogyny … Attentively negotiating a bleak world, the sentences remain joyous constructions … ‘Let it blaze!’ commands Woolf in Three Guineas. At their brightest, Ellmann’s own pyrotechnics are ones to savour.”

Things Are Against Us was also featured on the Lonesome Reader blog! The review was posted online on July 6, 2021, and can be read on their website here.

Reviewer Eric Karl Anderson wrote:

“This collection largely succeeds in distilling the author’s frustration about how we deserve better than the leaders we must live under and the systems we must live within. Ellmann wearily acknowledges towards the end of the book that “I recognize I’m fighting a losing battle—going up the down escalator” but I’m so glad she continues to march on and doesn’t allow herself to be silenced.”

Preorder Things Are Against Us today from Biblioasis here!

A GHOST IN THE THROAT

Doireann Ní Ghríofa’s A Ghost in the Throat received a rave review in the Globe & Mail! The article was published on July 2, 2021. You can read it on their website here.

Reviewer Emily Donaldson wrote:

“Electrifying and genre-bending … The book’s title conveys the uncanny feeling Ní Ghríofa had while writing the book, of having another’s voice emanate from her own throat … Ní Ghríofa’s quest sometimes feels like DNA-sleuthing, but with earth and texts taking the place of cheek swabs … The final act of reciprocity may be that one great work has ultimately spawned another. Ní Ghríofa’s book wouldn’t exist without Ní Chonaill’s poem, in the same way the poem wouldn’t exist without the death of Art O’Leary: both are rooted in agonizing, exquisite emotion.”

Buy your copy of A Ghost in the Throat from Biblioasis here!

And don’t miss out on our limited-edition signed hardcover copy here!

MURDER ON THE INSIDE

Catherine Fogarty’s Murder on the Inside: The True Story of the Deadly Riot at Kingston Penitentiary received a rave review in the Literary Review of Canada! The article “Inside Kingston Pen: So irksome and so terrible” was published online last week and will appear in the July/August 2021 issue. You can read it on their website here.

Catherine Fogarty’s Murder on the Inside: The True Story of the Deadly Riot at Kingston Penitentiary received a rave review in the Literary Review of Canada! The article “Inside Kingston Pen: So irksome and so terrible” was published online last week and will appear in the July/August 2021 issue. You can read it on their website here.

Reviewer Murray Campbell wrote:

“In Murder on the Inside, the writer and television producer Catherine Fogarty relates this notable chapter in Canadian history crisply and in greater detail than the various feature articles written over the years or even Roger Caron’s first-hand account of the event, Bingo!, from 1985. Remarkably, Fogarty gives distinct personalities to the inmates and puts us on the inside of the negotiations that ensued … Murder on the Inside tells a story that Canadians ought to know. Fogarty’s final chapter brings that story up to date and shows that we have not fully learned the lessons of 1971 … The ghosts who haunted those cold, dank corridors are still with us.”

Learn more about Murder on the Inside here!

THE DEBT

Andreae Callanan’s The Debt received a great review in the Toronto Star! The review was published online on July 1, 2021 and appeared in the Saturday, July 3 print issue. You can read it on their website here.

Reviewer Barb Carey wrote:

“Andreae Callanan’s appealing debut collection is an exploration of what is owed: an individual’s debt to family, community and place in forming identity and the present’s debt to the past. In the opening poem, the St. John’s writer offers a lyrical portrait of the island she calls home … In a sardonic suite of poems called ‘Crown,’ she looks at the history of settlement and colonialism, and the effect of being ‘outpost, not empire.’ Callanan’s phrasing is crisp, forthright and imbued with the music in commonplace language.”

The Debt was also featured in an article from the Peterborough Examiner! The article was published on July 1, 2021. You can read it on their website here.

Get your copy of The Debt from Biblioasis here!

WHITE SHADOW

Roy Jacobsen’s White Shadow also received a great review in the Toronto Star! The review was published on July 8, 2021, and it appeared in the print issue on Saturday, July 10, 2021. You can read the review on their website here.

Roy Jacobsen’s White Shadow also received a great review in the Toronto Star! The review was published on July 8, 2021, and it appeared in the print issue on Saturday, July 10, 2021. You can read the review on their website here.

Reviewer Janet Somerville wrote:

“White Shadow is written in spare, affecting, unsentimental, vivid prose … Kind gestures translate perfectly in this ‘land of silence,’ where Barrøyers are ‘folk of few words’ with ‘great wisdom in hands and feet.’ A minimalist tale of tenacity, White Shadow is atmospheric and compelling.”

Pick up a copy of White Shadow from Biblioasis here!