Want to get new excerpts, musings, and more from The Bibliophile right away? Sign up for our weekly online newsletter here!

***

During the 2023 London Book Fair I made what has become one of my favourite pilgrimages: to Hampstead Heath to meet the publishers of Sort of Books, Mark Ellingham and Nat Jansz. I became acquainted with Mark in 2019, when we took Canadian rights for Andri Snær Magnason’s On Time and Water, a book about global warming that Mark had acquired for Profile Books. When acquiring books, one also often acquires friends along the way: Mark and Nat rank among the best of these.

Before becoming an acquiring editor of nonfiction for Profile and starting up Sort of Books with Nat, Mark had been the creator and publisher of the Rough Guide series of travel and cultural books. Growing increasingly anxious about the environmental costs of rampant tourism and his company’s own contribution to the same, Mark sold the company and used the profits to devote himself to a different type of publishing program. That 2019 afternoon when we first met had been grey and threatening, the tall grass his dog led us through soaking the only pair of shoes I had with me, the dampness later rising up my legs as the Booker Prize ceremony that had brought me to London progressed, so that by the time the winner was announced, I was rather feverish. But the hours I spent with Mark wandering the heath, and then eating lunch at the Wells Tavern, were more than worth it, and, during the long days and weeks and months of the pandemic, took on an especially golden resonance.

The April day in 2023 when we next met was quite beautiful, and after another walk with the dog, and another lunch, we finished up with coffee in the front room of Nat’s and Mark’s house, which doubles as Sort of’s centre of operations. One of the pleasures of these fairs is talking with other people who understand the particular challenges and pitfalls of independent publishing, as well as its equally particular pleasures, which include the discovery of new books. At one point Mark put down his coffee and motioned me over to his computer: “Come take a look at this.” And he proceeded to tell me about Roland Allen’s The Notebook: A History of Thinking on Paper.

There is, at least for me, a covetous aspect to being a publisher: you learn of a book and feel an immediate quickening, a desire to have it for your list, or to be part of it in some fashion. This feeling overwhelmed me on first learning of The Notebook. Here, Mark told me, was the first book of its kind, a history of the notebook and the radical ways it has changed how we relate to both the world and to ourselves through a wide range of disciplines, from accounting and art to exploration, medical care, policing, and science. In the parlance of the antiquarian trade, I love BABs, or books about books, and here was a BAB quite unlike any other. Reading it transformed my own understanding of the role of this humble invention—but just as importantly, it’s changed how I use my own notebooks on a daily basis.

And judging from the response to the book since we first published it in September, I’m not alone. The Notebook has received rave reviews in the likes of Kirkus, Washington Post, Wall Street Journal, and The New Yorker; Ryan Holiday has sung its praises; and it’s been quite easily our best-selling book of the season.

There are so many wonderful stories within these pages, but one of my favourites concerns the zibaldone, an invention that changed our relationship, before the printing press, to literature, making it possible, in the world before print, for work by the likes of Dante and Boccaccio to travel far beyond the communities for which they wrote. Since reading this, I have begun to keep my own zibaldone as a notebook distinct from my others; perhaps some of you, once you finish reading this, will do the same.

Dan Wells

Publisher

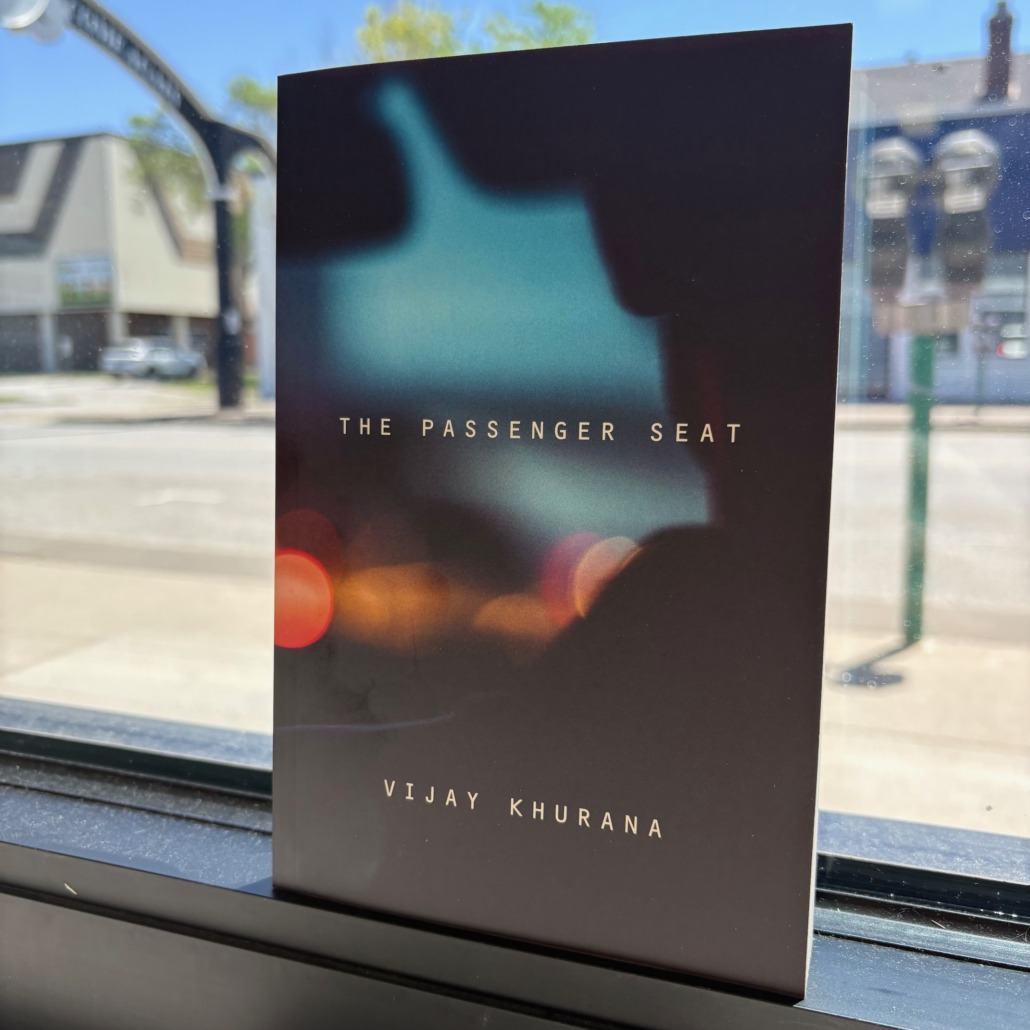

Photo: The Notebook by Roland Allen, with a cover designed by Louis Gabaldoni.

Excerpt from Chapter 4: Ricordi, ricordanzi, zibaldoni

Notebooks in the home, Florence 1300–1500

No-one knows exactly when the gloriously sonorous noun zibaldone appeared, or what it originally meant. The earliest record of the word, in the mid-fourteenth century, refers to it as Florentine slang, without further definition, and we can only infer from context that it means something like ‘mess’ or ‘jumble’. The fifteenth-century merchant and art patron Giovanni Rucellai referred to his own zibaldone as ‘una insalata di più herbe’, a salad of many herbs, which gives an impression of something variegated and wholesome. But by then it had also become firmly attached to the notebook in one of its most enduring applications. For this informal culinary term came to signify a personal anthology, or miscellany.

The basic principle was simple: when you found a piece of writing that you liked, or found useful, you copied it out into your personal notebook. You could copy out as much or as little as you wanted, neatly or not, and refer to it a little, or as much, as you wanted. The collection could be poetry or prose, fictional or factual, thematic or random, religious or profane, in Latin or Tuscan, or any mixture of any of these components; you could even draw pictures in it. The notebook itself could be large or small, luxurious or utilitarian. Some better-off writers, such as the author Boccaccio (the son of a Bardi banker), had zibaldoni made of expensive parchment, and paid professional scribes to do the writing for them. Many users illustrated them, or commissioned elaborate initial capitals to open every new excerpt: surviving examples often have gaps where their owners never got round to completing that task.

Mostly they were kept by men, but not all were, and we can assume that many wives, sisters and daughters would have had access to the books kept by the men of the house. For zibaldoni, although always idiosyncratic and personal to their owner, were not necessarily private, or intimate: you would share the highlights of your own with your friends, and if you saw something that you liked in theirs, you’d copy it over. You could sell a full zibaldone, or hand it down to your heirs, and in many examples one can see where the father stopped writing and the son took over.

Some even caused family disputes. ‘This book was written by Piero di Ser Nicholo di Ser Verdiano, for his own contemplation, and that of his family, etc. in the year of Our Lord 1458’ reads an inscription at the beginning of one notebook, before writing that Piero intends the book to go to Girolamo di Piero Arighi, presumably his son. Beneath this is a crossing-out, and under that another hand writes ‘Note that you are lying through your teeth like the scoundrel you are, and you are a crazy windbag.’ Was that inserted by Girolamo’s brother, Bartolomeo, who elsewhere in the zibaldone claims ownership?

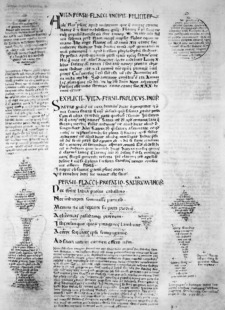

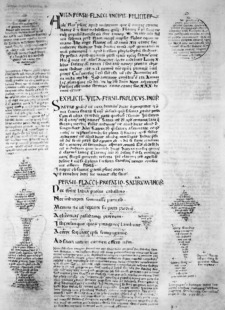

The son of a banker, Boccaccio could afford to pay scribes to compile his zibaldoni. This playful layout has extracts from the Roman poet Flacco.

What did people write in their zibaldoni? In a word: everything. Poems in Latin, poems in Tuscan, prayers, excerpts from books, songs, recipes, lists, you name it. Lisa Kaborycha, who has studied them extensively, points to one fifteenth-century example which, entirely typically, contains material as various as ‘remedies and recipes, interpretations of dreams, astrological predictions, advice on the best times for planting, Pseudo-Saint Bernard’s Epistle to Raymond, prayers, poems, ballads and a number of sonnets by Coluccio Salutati, Antonio Pucci, and Dante.’ Armando Petrucci, another expert, celebrated the zibaldone for preserving ‘gate tolls and currency exchange rates . . . alongside medical recipes, devotional tracts, lauds, and love lyrics’.

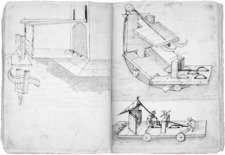

Rucellai compiled his zibaldone with his sons in mind: for their benefit, it contained moral precepts, advice on business and civic duties. In his, the sculptor Ghiberti collected translations of Vitruvius and Pliny, drawings of Roman architecture, a history of Florentine and Sienese art, and his own memoirs. Through these he interlaced his own theoretical ideas—on optics, proportion, anatomy—clearly intending the collection to form the basis of a humanist art education. His grandson Bonaccorso, who inherited them along with the family business, left his own notebooks, which quote from his grandfather’s and add numerous diagrams of bells, cannon, cranes and hoists. So no two zibaldoni are the same.

***

Florentines loved their new hobby. Looking at the zibaldoni in the archives, researchers can track how the notebooks grew in popularity over time, peaking in the fifteenth century as Florence enjoyed its second heyday as the hub of Europe’s intellectual life. Books had now become everyday items, and this had profound effects on how ordinary people enjoyed the written word. Literature, previously only available in monasteries, universities, courts and a few other privileged locations, now moved into the home: the kitchen table and shop counter joined the tilted desk of the scriptorium as a place where a book could be read, or written. People read in a new way in these new locations too. They enjoyed a wave of authors writing in their local tongue—not just Dante, Petrarch and Boccaccio, but a host of other writers forgotten today—and, unlike a student or a cleric in an institution’s library, they could read privately, even in bed.

We should note, too, that the labour involved in copying out a chunk of literature changes the way the copyist relates to it. Transcribing a poem or letter forces the writer to read it multiple times, paying attention to the fine details of word selection and word order, and to consequently enjoy what one scholar calls ‘a more intimate and meaningful experience than they could have with purchased texts’. You only take on the significant labour of such copying if you really enjoy the text, and you then find that you come to know it and appreciate it much better.

How did this new habit relate to the continuing work of traditional scribes? Historian Ross King has described a thriving culture of high-end manuscript production in Florence, where professional scribes and notaries—and the secretaries of some rich men—produced formal manuscript copies, nearly always on parchment, to order. Such copies could be extremely beautiful, and the booksellers who commissioned them for their wealthy clients took great care about their texts. King relates, for instance, how the great bookseller Vespasiano da Bisticci (1421–98) would compare multiple extant copies of an ancient book—for instance, Pliny’s Natural History—in order to make sure that his new version was as faithful as possible to its author’s intentions. Scribes moved their pens differently, dropping the baffling vertical strokes of traditional gothic script and adopting the beautifully lucid ‘antique’ or humanist style, recommended by Vespasiano’s contemporary Poggio Bracciolini (1380–1459) in its place.

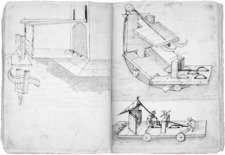

Bonaccorso Ghiberti recorded many of the machines that Brunelleschi developed for the construction of the dome of Florence cathedral.

Funded by wealthy patrons like Cosimo de’ Medici,* and scouring Europe’s monasteries for rare Dark Age survivals of classical texts, Vespasiano, Poggio and their peers kept up a steady supply of beautiful manuscripts filled with fresh translations, rediscoveries and new literary works. The presence of the papal court in Florence for several years also drew scholars to the city, and stimulated a rich intellectual life centred on the new libraries and bookshops where bookworms met to discuss their reading. This high-end literacy undoubtedly had a profound impact on European culture, giving the Renaissance its intellectual heft, and King celebrates its heroes, such as the legendary fourteenth-century scribe who produced one hundred copies of Dante’s Divine Comedy, whose sales contributed to his many daughters’ dowries.

But such painstaking efforts in expensive parchment codices could only ever find an elite audience. For Dante to become widely read, universally celebrated and the foundation of a new literature—in short, for Dante to become Dante—scribal reproduction would not alone suffice. His writings were transmitted to a much larger, more diverse, audience, by thousands of ordinary people copying favourite texts from zibaldone to zibaldone, reading and re-reading them at home, and sharing them with friends and family. And they copied not in the formal gothic or antique scripts that took years to master, but the rapid cursive scripts used by merchants and notaries; people who had to write accurately, but also quickly.

***

So notebooks democratised literature by giving readers another way to read; but they also gave writers another way to write. Petrarch (1304–74), another favourite of zibaldone keepers, adopted the habits and materials of notaries, the legal professionals who formed a crucial part of the mercantile ecosystem, and today’s scholars can trace his ideas as they progress from notes on loose leaves of paper to rough copies in paper notebooks and finally to completed books in a definitive version on prestigious parchment.* The intermediate stage, in the notebook, was creatively the most important and could last a while: Petrarch worked on the verses in Il Canzoniere for forty years (this was an age before publishers’ deadlines). Such labours definitely paid for themselves: by the time of his death, the poet had been crowned poet laureate in Rome.

In the zibaldoni of Petrarch’s friend Boccaccio (1313–75), we can see how the notebook helped writers in other ways, giving them a place to collect influences for future reference and quotation. As a young man, Boccaccio endured a miserable commercial apprenticeship at the Bardi bank, where his father was a partner, before breaking away to write full-time. He left no fewer than three zibaldoni, two written by scribes on parchment, and one rough notebook, known as the Zibaldone Magliabechiano, that he kept himself. Scholars have pored over them to discern his influences and their impact on his work, including the Decameron, and they betray an impressive depth of reading: a life of Mohammed, Euripides, Pliny, letters to and from Petrarch, and so on. In turn, his own work would feature in many zibaldoni, juxtaposed with—thrown into dialogue with – classical authors like Aristotle, Cicero and Seneca.*

***

Was Florence unique in all this? Yes and no. Notebook-keepers across Europe also made their own informal personal anthologies: examples survive from Scotland to Poland, and a vast majority of such books must have been lost or pulped many centuries ago. In the late 1300s, Dutch and German adherents of the devotio moderna—‘modern devotion’—movement were encouraged to keep rapiaria. The name for these notebooks derives from the Latin rapere, meaning to seize; we might call them ‘grab-bags’. In these devotional notebooks, the pious collected phrases or ideas from their scriptural reading, and added their own spiritual insights; the act of writing led to further rumination, helping the writer benefit from the wise words they copied. The Imitation of Christ—a hugely popular book—started life as the rapiarium of its author, Thomas à Kempis, a monk from Zwolle. Most rapiaria remained private, though, and were often buried with their owners, and the practice died out within a century.

But the people of Florence (and its environs) grasped the possibilities faster and more fully than anywhere else. Enriching their lives by ensuring that their favourite literature was always near at hand, they made it possible for a new writer to quickly find a wide audience. Most households had a book or two on a shelf and book-copying and production here outstripped that of every other city in Europe. One study of the period by the scholar Christian Bec shows that in the posthumous inventories of 582 deceased Renaissance Florentines, no fewer than 10,574 books were listed: an average of eighteen each.

Small wonder that Florence made a congenial home for the scholars, who would turn rediscovered classical texts into the keys of Renaissance humanism. In the city’s yeasty literary culture they could find a receptive readership, confident in their vernacular, ready for the translations, glosses and new works that humanists created, for they had already been enjoying the ancients for generations, ‘and knew the value of their wisdom’. Here too, new literary practice developed: authors could easily collect models and inspirations for their own work, could adapt the techniques of lawyers and merchants to help them hone it, and then rapidly find a wide audience in a well-read population that shared ‘content’ that we would today call viral.

Ricordi, ricordanzi and zibaldoni arrived in the thirteenth century as Florence established its commercial pre-eminence, grew in popularity over the course of the fourteenth as the city’s first great writers and painters made their impact, and peaked in the fifteenth, as the Renaissance flowered. In all three genres, and in the innumerable hybrid notebooks that refused to fit neatly into any category, Tuscans rich and poor recorded their place in society and celebrated a burgeoning culture of which they were justly proud.*

Footnotes:

- By 1444, when Cosimo opened the new library of San Marco, filling it with manuscripts he also donated, the tribulations that his predecessor Foligno had detailed were far behind.

- It is striking to note that notaries were trained to strike through phrases as they transferred them from their working draft (bastardello) to the final version, just as bookkeepers struck through transactions which had been reconciled to debit and credit. Petrarch’s father and grandfather had both been notaries.

- There’s more to literature than poetry, of course. Just ten years before Dante started work on the Divine Comedy, Marco Polo was coming up with Europe’s first international narrative non-fiction bestseller. Locked up in a Genoese jail with his amanuensis Rustichello da Pisa, Polo wrote his autobiographical Travels in around 1298. Sadly, we have no autograph manuscript and know nothing of how they composed the work.

- Literacy rates are notoriously difficult to prove, but there is strong evidence that they were higher in Florence than nearly everywhere else. Eight out of ten 1427 tax returns, for instance, were written by the taxpayer responsible, indicating a high rate of writing skill among property-holders. The historian Ronald Witt concluded that the city enjoyed rates of literacy ‘not seen again in Europe for another three or four centuries’.

Photo: Author Roland Allen signing copies of The Notebook at the Windsor book launch in Biblioasis Bookshop, September 30.

***

In good publicity news: