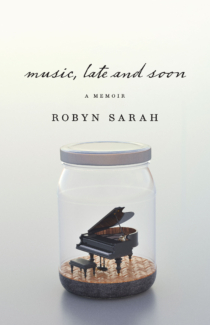

A decade and a lifetime in the making, Robyn Sarah’s Music, Late and Soon will be available to readers August 24, 2021. A memoir of a young woman’s career in music, which she leaves (for a variety of reasons) for writing, and returns to much later in life. An enticing ‘what-if’ story for the many people who abandon music in their youth and contemplate a return, but feel it’s too late. Sarah has spent the past decade with her first love, the piano, and has spent much of this time re-connecting and learning through celebrated teacher Phil Cohen. As a well regarded and award-winning poet, Sarah explores the relationship between the verbal and non-verbal arts, and verbal and non-verbal learning. A memoir of artistic vocation, it will be intriguing to music and poetry readers alike.

Q1: Can you provide a brief introduction to those readers who are not familiar with your work?

A1: Writing has been a constant in my life for as long as I can remember. I had it in my head from the age of six or seven that I was going to be a writer when I grew up, and that remained a lodestar for me through a lot of digressions – notably ten years in music school, when I thought I was headed for a career as an orchestral musician. I graduated from the Quebec Conservatory in the early 70s with a diploma in performance on clarinet, but abandoned music as a career path soon after, and eventually became the writer I always meant to be. Like many of my fellow writers in Montreal, I taught English in Quebec’s junior college system for many years, but since the mid-1990s I’ve worked as a freelance writer and literary editor, most recently serving ten years as poetry editor for Cormorant Books. Poetry is my primary genre. Though I’ve also published essays and stories, I think my poet’s perspective leaves its stamp on everything I write.

Q2: Music, Late and Soon chronicles another decade-long – to use your word – digression, a return to the serious study of music after more than three decades. “I was late for my piano lesson,” your memoir begins. “Thirty-five years late, to be exact.” Can you tell us a bit about why, at such a stage in your life, you returned to music, and perhaps a bit about the genesis of this book?

A2: Who can say with certainty why we do anything we do, and why at a particular moment? Human motivation is so layered. We have conscious motives, we have unconscious motives, we have intentions and impulses. We have game-changing encounters with chance. When we say, “It was just something I had to do at that moment”, we may not even know what tipped the balance. But when we make such a statement, we’re on our way to telling ourselves a story. This book is the story I told myself to explain why, at nearly sixty, I had to take piano lessons again – something I had thought about doing many times before without acting on it.

Robyn Sarah, age 8

– Which leads to your question about the genesis of the book. On this particular occasion, the thought came simultaneously with the idea of writing a book about it. And somehow, it was the book – the untold, unlived story I sensed there – that made it possible for me to do what I hadn’t been able to do before. I felt propelled into simultaneously living the story and writing it. At first I thought it would be a much shorter book – a story about a year of late-life piano lessons, leading to a small recital. I didn’t know it would take me back to my years in music school. I didn’t know it would demand that I finally make some sense of my abandoning a career as a clarinetist just as it was getting off the ground. It was only in the bringing together of both processes – my literary process and a return to serious musical practice on my first instrument – that the living and the writing overflowed those initial parameters.

Q3: You’ve explained how writing about your return to music took you back to your musical past. Can you say a little about where that return has taken you as you’ve moved forward?

A3: Well, it wasn’t very long before I realized this was no caprice. It wasn’t even a “project” – not in the sense of something I could finish and walk away from. I realized I was back at the piano for the long haul. I had dropped any expectations; I was open to wherever it wanted to take me. The second part of the book describes some of the places it initially took me – among them, playing piano in local cafes and a retirement home; playing a small private recital beset with unexpected challenges; attending a three-week summer piano intensive where I was the oldest participant by – you guessed it – thirty-five years. It also brought me new friends, new repertoire, new perspectives, and a sense of ongoing adventure as I entered my sixties.

Q4: Your memoir chronicles more than a return to and relationship with an instrument (or many instruments, several pianos and clarinets both!); it also tells the story of a special relationship with a very special teacher. Can you tell us a little about this?

A4: Philip Cohen’s legacy – very much his own, but at only one remove from celebrated pianist Alfred Cortot, who taught his teacher – lives on in the teaching of his students in Montreal, New York, Chicago, L.A. and overseas, all of whom acknowledge his extraordinary qualities. I began studying with Phil at eleven, stopped at seventeen, and returned briefly in my early twenties. When I came back to him at 59, I never imagined I would end up studying with him again for nearly nine years – the same length of time as I did earlier in life. My adult years as mother, teacher, and writer were book-ended by those two periods of intense musical mentorship. This “late and soon” aspect of our relationship was one thing that made it special. But everyone who studied with Phil Cohen had a special relationship with him, and everyone’s was different. His approach to teaching was based entirely on his appreciation of the individual human being: you felt he understood you better than you understood yourself, that you had his full attention, and that he cared. Not only were his musical insights endlessly inspiring, but regardless of age, background, or personality, he was able to reach people on a soul level.

Q5: The initial goal of this project was to return to piano for a year, to ready yourself for the possibility of performance, and to write a short book about the experience. Both book and the experience it chronicles became much more than this, and I think Music, Late and Soon is, among other things, one of the best books on artistic dedication and vocation I’ve read. Can you highlight a few of the things you learned along the way?

Q5: The initial goal of this project was to return to piano for a year, to ready yourself for the possibility of performance, and to write a short book about the experience. Both book and the experience it chronicles became much more than this, and I think Music, Late and Soon is, among other things, one of the best books on artistic dedication and vocation I’ve read. Can you highlight a few of the things you learned along the way?

A5: When I first approached my teacher with the project of spending a year working to prepare a modest recital program, his response was, “Why would you not just start working again and see where it leads? Playing the piano is like any art form, any creative process – it doesn’t work by deadline.” I think the primary thing I learned as we worked together anew was to respect creative process – to trust it and to recognize the patience it requires. Not just at the piano, and not just in my writing, but in living life. The book became as much a meditation on creative process as it is a personal story. Many of the things I learned were actually things I had learned before but found myself relearning on a deeper level. This itself was one of them: that serious learning is a process of coming back again and again to deepen acquaintance with something we think we know.

You can order a copy of Music, Late and Soon here.

We’re thrilled to share that Music, Late and Soon by Robyn Sarah (August 24, 2022) has been shortlisted for the 2022 J.I. Segal Awards Best Quebec Book on a Jewish Theme! The shortlist was announced on September 21, 2022. Check out the full list here.

We’re thrilled to share that Music, Late and Soon by Robyn Sarah (August 24, 2022) has been shortlisted for the 2022 J.I. Segal Awards Best Quebec Book on a Jewish Theme! The shortlist was announced on September 21, 2022. Check out the full list here.